At consulate in Libya, a model diplomat is lost

WASHINGTON — J. Christopher Stevens was in many ways the model American diplomat, committed, idealistic, willing to take risks and eager to find out what was really happening in obscure corners of the world.

A lanky 52-year-old Californian, with a burst of brown hair, Stevens also looked the part.

“He was always smiling, unruffled, projecting what I think of as a cool California demeanor, in the best sense,” said Robert Danin, a former Middle East hand at the State Department who worked closely with Stevens.

PHOTOS: Consulate attack in Libya A UC Berkeley graduate who was confirmed as ambassador to Libya in May, Stevens well knew the dangers inherent in his hands-on style.

From 2007 to 2009, he served as the No. 2 U.S. diplomat in Tripoli after the U.S. resumed diplomatic relations with Col. Moammar Kadafi’s government. And last year, during the height of the revolution that eventually toppled Kadafi, he secretly slipped back into Libya aboard a Greek cargo ship to serve as U.S. envoy to the rebels battling the strongman.

“We had a bombing at the Tibesti [Hotel] the other day — a reminder that Benghazi isn’t safe,” he emailed an acquaintance in June 2011, referring to the building where he and other diplomats were staying.

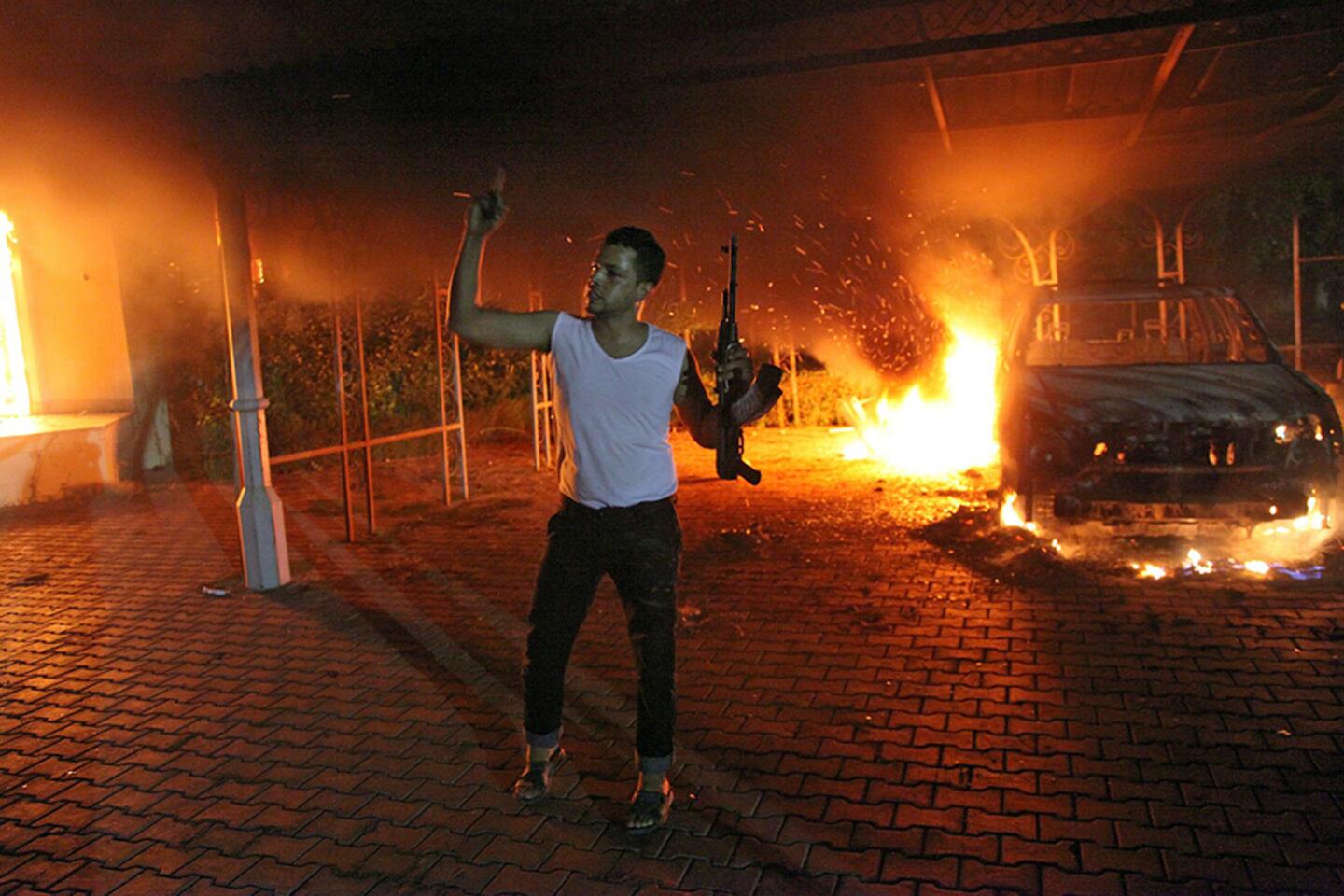

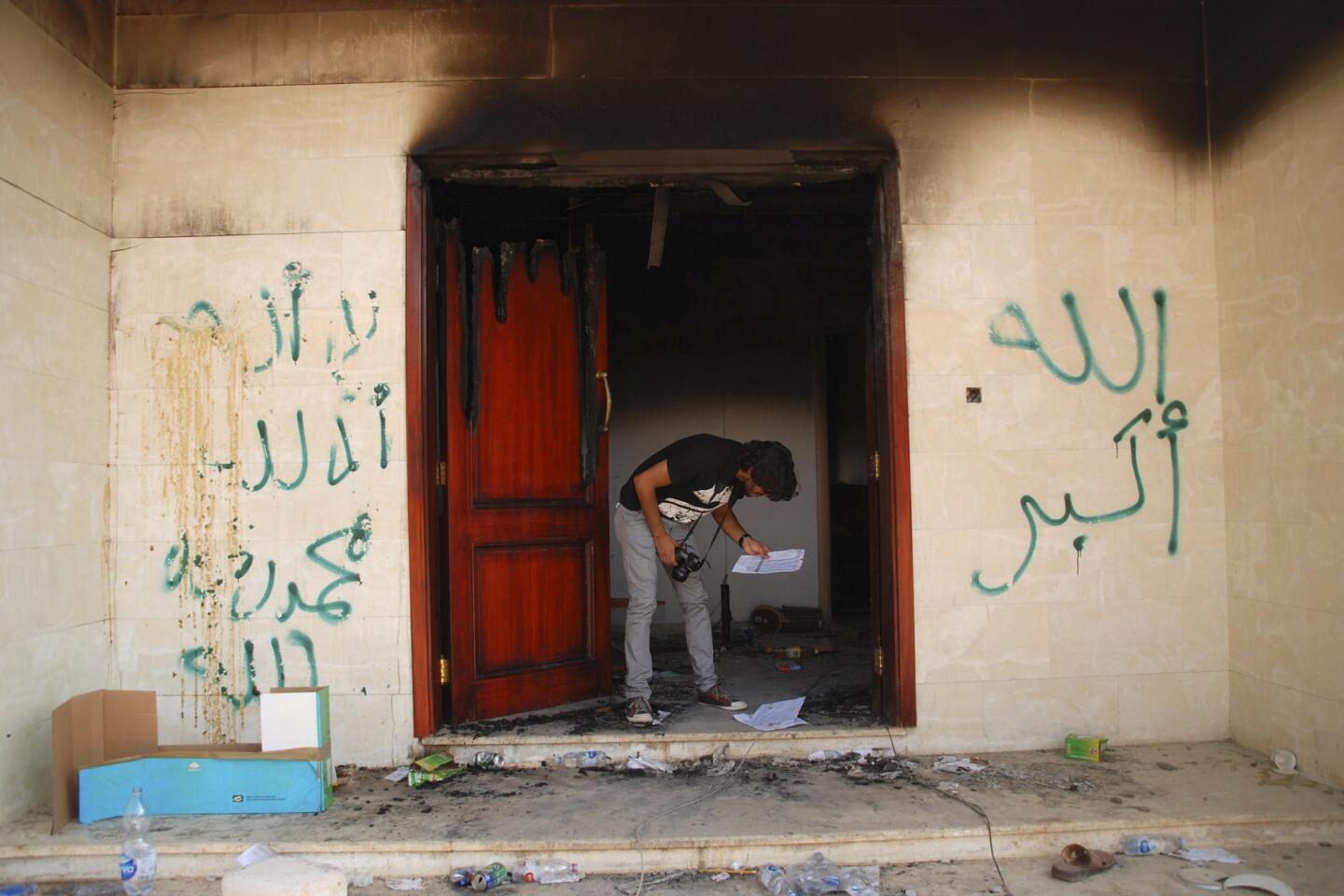

On Tuesday, in an attack on the U.S. Consulate in Benghazi, the lawyer-turned-diplomat became the first American ambassador to die in the line of duty since 1988. Three other Americans were also killed in the assault by heavily armed attackers in violence that followed a street protest outside the American facility in eastern Libya.

Stevens’ friends and superiors, including Secretary of State Hillary Rodham Clinton and President Obama, said Wednesday that his rush to help evacuate others from the building was a reminder of his commitment to the country.

“He risked his life to stop a tyrant, and gave his life trying to build a better Libya,” Clinton said in an emotional appearance at the State Department. “The world needs more Chris Stevenses.”

Stevens grew up in the East Bay community of Piedmont, graduated from UC Berkeley in 1982 and UC Hastings College of the Law in San Francisco in 1989. His first service overseas was as a Peace Corps volunteer in the Atlas Mountains of Morocco.

He was the son of a lawyer, Jan Stevens, and a now-retired Marin Symphony cellist, Mary Commanday.

His stepfather, Robert Commanday, a former classical music critic for the San Francisco Chronicle, when asked about his stepson’s musical pursuits, told a classical music website that Stevens “played saxophone, about at the Bill Clinton level, but marginally in public.” He also was a tennis player and a Lakers fan, passions that he tried to maintain in Libya.

After law school, Stevens worked for two years as an international trade attorney in Washington. But it didn’t satisfy him, and at the relatively late age of 31, he joined the foreign service.

Stevens revealed a bit of himself, and a bit of the diplomat’s art, in a video he prepared for the Libyans and displayed on the embassy’s Facebook page before he arrived in the country to take on the ambassador’s post.

The video, which shows Libyans exulting at their new liberty, has shots of Stevens as a young man, tramping through California mountains wearing a backward baseball cap, and celebrating with his family at his law school graduation.

He was also pictured in a more contemporary scene strolling through official Washington, posing in front of Congress and gazing at the statue in the Lincoln Memorial. “I look forward to watching Libya develop equally strong institutions of government,” he said.

When he was confirmed as ambassador in May, he said he considered it “an extraordinary honor.”

Fluent in French and Arabic, Stevens previously worked in a variety of Middle Eastern posts, including ones in Jerusalem; Cairo; Riyadh, Saudi Arabia; and Washington.

Colleagues described him as friendly, casual and rarely rattled. He also was candid, a trait that won him fans among Arabs and a following among journalists who covered Middle East hot spots.

Stevens had a yearning to mingle with Arabs to get a street level view of events, and he sometimes chafed about the post-Sept. 11 security measures that sometimes prevented diplomats from reaching far into the hinterland. As political officer in Jerusalem, given the oft-touchy assignment of working with the Palestinian leadership, he tried to get out into the West Bank even when violence flared between Palestinians and Israelis.

Stevens relished contacts, even with some of the region’s unsavory personalities. In one of the U.S. diplomatic cables released by the WikiLeaks website, Stevens described Kadafi as “notoriously mercurial” but also, on occasion, “an engaging and charming interlocutor.”

The impression he made among Libyans was apparent on Wednesday.

“Chris Stevens was a friend to all Libyans,” read a poster carried by an admirer in Benghazi, a Twitter image showed. “Sorry, people of America, this is not the behavior of our Islam and prophet,” read another.

Times staff writers Patrick J. McDonnell in Antakya, Turkey, Nan Wang in Washington and Lee Romney and Maria L. La Ganga in San Francisco contributed to this report.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.