Imagine the chaos if lower courts refused to abide by a Supreme Court ruling. That’s happening in Turkey

Turkey risks being plunged into a constitutional crisis, human rights groups and legal experts warn, as lower courts refuse to comply with a ruling by the country’s top court ordering the release of jailed journalists.

The crisis has shaken advocates for the rule of law and could have consequences for Turkey’s membership in several European bodies.

The standoff began on Jan. 11, when Turkey’s Constitutional Court ruled 11-6 that two journalists being tried by lower courts on charges of terrorism for links to a 2016 coup attempt must be released from prison pending a verdict. But four separate lower courts have refused to comply.

“The lower court rulings are shocking,” said Nate Schenkkan, a project director with Freedom House, a Washington-based watchdog organization. “Once the top court has issued a ruling, it has to be obeyed, there is no way around it. If the government wants to change the constitution, it can do that, but this is not the case. This is just a lower court saying, ‘You are superior, but we think you are wrong.’ ”

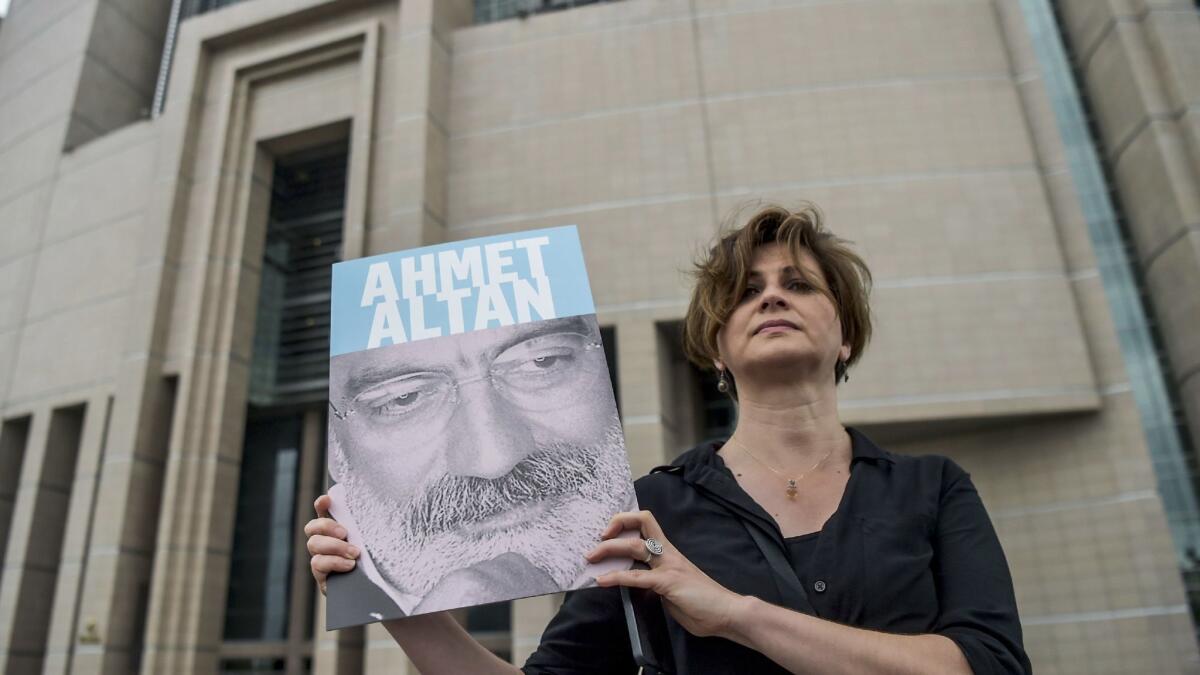

The case at the center of the controversy involves Şahin Alpay, a political science professor, and Mehmet Altan, an economist, both columnists at leading newspapers. They were detained in July 2016, accused of ties to Fethullah Gulen, the cleric blamed for the failed coup that killed 250 people. Alpay wrote a column for Zaman, a newspaper linked to Gulen that has since been shuttered, and many of its editorial staffers are being tried in similar cases.

Gulen’s organization has been declared a terrorist group by Turkey.

In court, both men told judges they had no knowledge of the coup plot. Both face aggravated life sentences on charges that include “attempting to overthrow the government” and having “prior knowledge of the coup attempt.”

The Constitutional Court found that the journalists’s pretrial detentions were disproportionate. While their trials could continue, the top court said the defendants must be released from custody.

Long periods in pretrial detention, Schenkkan said, were one target of a package of constitutional amendments approved in 2010 that allowed individual petitions to the Constitutional Court. Now, he said, it appears that the government of President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, which pushed through those reforms, is trying to undo them.

More than 50,000 people are in detention, including more than 150 journalists, many facing terrorism charges, and Turkey has been under a state of emergency for more than 18 months.

Turkey and the U.S. used to be close allies. Today, they can’t even agree on a phone call »

The move by lower courts, critics of the government say, appears to be a political decision, taken under pressure to prosecute Gulen’s suspected followers. A day after the superior court’s order, Deputy Prime Minister Bekir Bozdağ said on Twitter that “the Constitutional Court has gone beyond the limits set by the constitution and the laws.” Prime Minister Binali Yildirim said the lower courts had “full knowledge about the case,” and they should be the ones to decide on the detention of the defendants.

Legal experts, meanwhile, pointed out the basis of the ruling had little to do with the case, but with fundamental rights that had been violated by the long detention of Alpay and Altan. The lower courts “must immediately comply with the Constitutional Court’s ruling,” Metin Feyzioglu, head of the Union of Turkish Bar Assns., told a conference of legal experts in Istanbul. “There is no need to have doctoral or professorial knowledge to understand this.”

It is not the first case of the government expressing dismay with a ruling by the Constitutional Court. In 2016, judges ordered two journalists, Can Dundar and Erdem Gul, released pending a lower court verdict on treason charges, as part of an investigation into news coverage that alleged the Turkish government was supplying weapons to Islamic State militants in Syria.

“I can only remain silent on this decision. But I can’t accept it. And I neither obey the decision, nor respect it,” Erdogan said at the time. Dundar fled Turkey after his release and now lives in Germany.

The apparent sidelining of the Constitutional Court could have serious implications for Turkey’s membership in the Council of Europe, Schenkkan said. Turkey’s Constitution acknowledges that the European Court of Human Rights has jurisdiction in the country, but so far that body has been careful to allow domestic courts to rule first on issues before stepping in.

The European court, which is based in Strasbourg, France, and monitors human rights in Council of Europe member states, has historically been inundated with petitions from Turkey, which accounts for the largest share of judgments issued since the court was formed in 1959. Asking petitioners to exhaust domestic legal remedies, said Schenkkan, was one way the European court tried to cut down on that workload.

In November, the European court announced it would not review more than 25,000 petitions related to the purge of about 150,000 civil servants in Turkey since the coup attempt, saying the applicants should first try a new state of emergency commission set up by Ankara to review the cases. The ruling was in response to an appeal by Turkish academics who were fired because they signed a petition calling for a cease-fire with the Kurdistan Workers’ Party, a separatist group Turkey and its allies in the North Atlantic Treaty Organization have declared a terrorist organization.

Although punitive measures by the Council of Europe tend to take years, Schenkkan said an important precedent was being set by Azerbaijan. In 2014, the European Court of Human Rights ruled an opposition politician and blogger must be released, and in December, the Council of Europe opened proceedings that could expel the country from the organization.

ALSO

7 staff members of opposition newspaper leave Turkish jail

Turkish court jails an Amnesty director and 5 other human rights activists pending trial

Turkey says U.S. ‘stabbed us in the back’ by aligning with Kurds on Syrian border

Farooq is a special correspondent.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.