Great Read: How a Safeway checker (who raps) got his break in video game biz

At the Safeway in the Oakland Hills, co-workers call checker Roberto McCoy “the Experience.”

Customers always remember him. He’s worked here eight years, and he’s usually smiling, bopping his head and mouthing rhymes.

McCoy calls himself Visualeyes — Viz for short — when he’s making music. He records in his bedroom, burning CDs with his computer.

He believes in sharing his music, so he made 100 CDs and gave them away to shoppers at the store.

He was down to his last one when David Robinson, a video game developer, came through his checkout line.

“Merry Christmas,” McCoy said, dropping his gift into Robinson’s bag late in 2013. “I’m a rapper. This is my music.”

::

The CD migrated around the inside of Robinson’s 2007 Chrysler Crossfire for months. It was stuffed inside one of the seat pockets, then hidden under piles of junk on the floor. At one point, Robinson used it as a drink coaster.

The CD eventually found its way into the trunk and was covered in chocolate chips. Last summer, a worker at a carwash found it and asked Robinson if he wanted to keep it.

“Nah, just throw it out,” Robinson recalled saying.

“You sure, homes? It’s got writing on it. It looks important.”

Robinson shrugged.

“OK. Just leave it in the car.”

Robinson, his curiosity piqued, put the CD in his car’s player as he pulled into his driveway.

McCoy’s voice alternated between lyrical melody and staccato bursts. He could be calming in one break, aggressive in the next. The crudely mixed tracks captivated Robinson. He bit his fist to stop himself from screaming with delight.

“This is it! This is it!”

He headed for the Safeway to find that checker.

::

Robinson is a veteran game developer, having worked on popular titles including “Crash Bandicoot” and the “Gex: Enter the Gecko” series. He worked as a producer for Universal Studios, Crystal Dynamics and Namco Bandai before recently founding Redacted Studios.

Last year, Robinson was searching for fresh musical talent for his studio’s game, “Afro Samurai 2,” a sequel to the 2009 action-adventure game based on the titular manga and cartoon series. The first game had voice acting from Samuel L. Jackson and music direction from rap artist Rza of Wu-Tang Clan.

Hip-hop would play an even bigger role in the sequel. A Bay Area native, Robinson preferred local and relatively unknown rappers, like some who had worked on the first “Afro Samurai.”

This approach had proved tricky for the sequel. Oakland had no shortage of rappers, but Robinson wanted someone who could hit the “Afro line,” an elusive concept that even he has trouble describing.

Robinson talked about the Afro line evoking a sense of honor, betrayal, familial love, resentment, brotherhood and revenge — all themes that run deep in the “Afro Samurai” game series. When those words failed at articulating what he wanted, he resorted to calling it a feeling — a “hotness.”

The complexity of the music matches that of the game itself — a story set in a world inspired by hip-hop about a black swordsman living in a futuristic feudal Japan.

::

At the Safeway, McCoy was chatting to a customer when Robinson appeared next to him.

“Dude, I love your music,” Robinson said.

McCoy had made fans of shoppers before, and it never got old to hear that people liked his music.

“Thanks, man,” McCoy recalled saying.

“I’m the lead engineer and director for ‘Afro Samurai,’” Robinson told him. “I’d like to schedule a meeting with you.”

“Uh …OK” was all McCoy could muster.

They gathered in Robinson’s living room a few weeks later. McCoy thought Robinson wanted to use the music from the CD in the game.

Robinson made it clear he wanted new tracks. He would show McCoy storyboards from “Afro Samurai 2,” then send him home to make music. McCoy would be paid for each song used, and the rapper would retain the rights once the game is released.

After a few weeks of writing and recording, two friends and fellow rappers — 22-year-old Terry “Tarantikno” Benjormen and 23-year-old Noah “Nay Steez” Stein — were also brought on to compose music for the game under the same terms.

Benjormen was fast and energetic, often rapping with such speed he sounded like a tape on fast-forward. Stein was the opposite. His style was slower — leisurely, deliberate. When the three of them rapped in succession, it felt like a three-part act, each rapper telling a different story through rhythm, sound and feel.

::

None of the songs the trio submitted satisfied Robinson.

The rappers couldn’t figure out what Robinson wanted, and Robinson was on a deadline. “Afro Samurai 2” was conceived as a three-part episodic game, and the first part was due to launch in early 2015.

Robinson panicked.

Game studios typically pay professional musicians and composers to write a score. They don’t give a group of amateur rappers free rein over the music they create, especially when that music is the cornerstone of the game.

The three were delivering new tracks every week, but Robinson felt that the music lacked the emotion that had gripped him when he first heard McCoy’s CD.

“I need you to hit that line,” Robinson kept repeating.

McCoy couldn’t decipher what that meant, and Robinson didn’t know how else to say it. Everyone became frustrated.

Robinson was ready to give up when he tried something different. It occurred to him that McCoy had rapped in the style he wanted before he had ever heard of “Afro Samurai.”

“Just make music for you,” he told McCoy.

“So forget the Afro line?” McCoy asked.

“Yes,” Robinson said. “Just make it for you.”

::

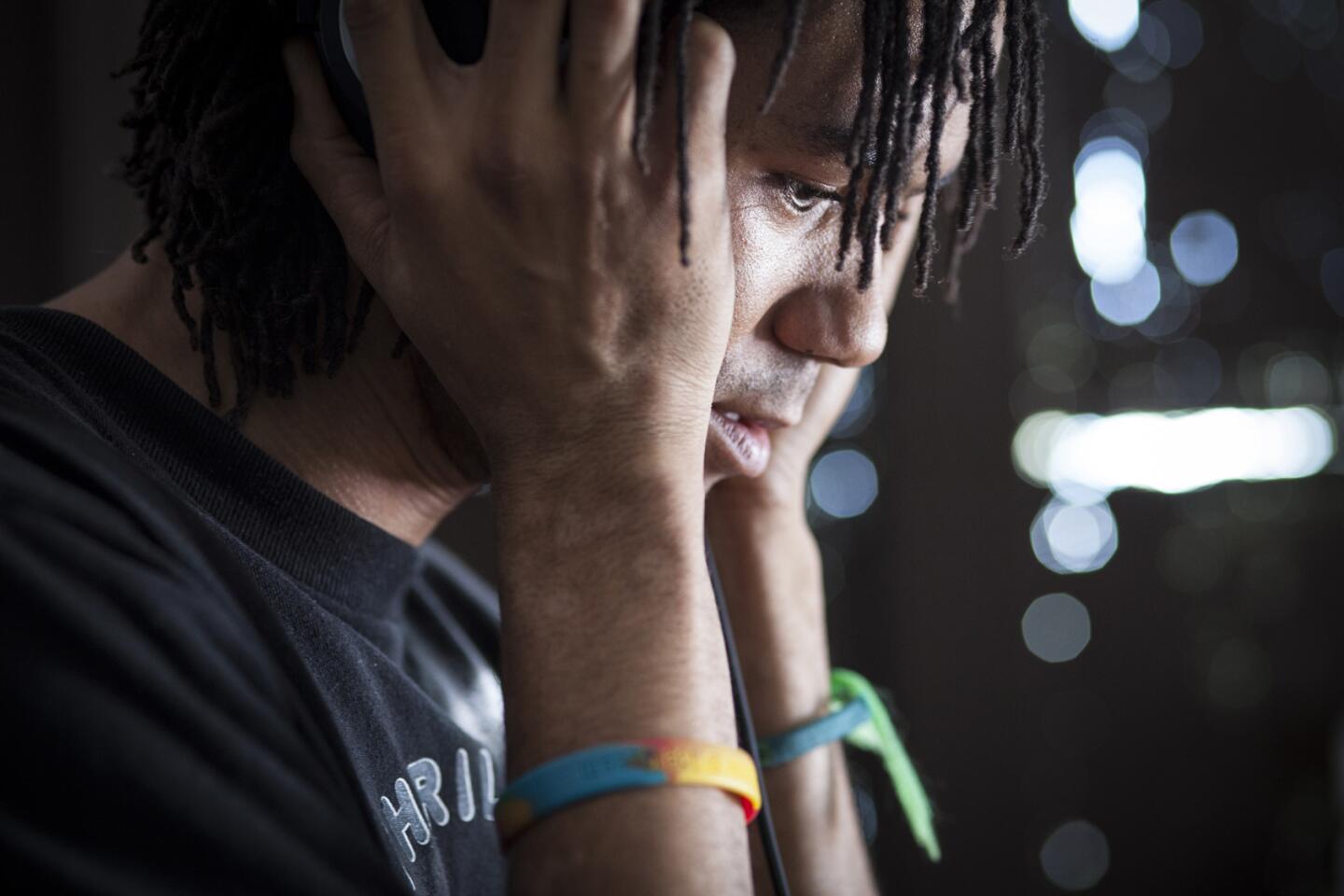

Weeks later, McCoy, Benjormen and Stein sat in a darkened studio in Robinson’s home, a couple of miles from the Safeway where McCoy still works.

Freed of pressure, McCoy had delivered an album in the same style as the one he’d first dropped in Robinson’s grocery bag — aggressive rhymes, broken up by melodic vocals.

Robinson loved it. He called in producer Daniel Fouché, who had worked with Living Color and Chuck D from Public Enemy, to help polish the recordings.

After adjusting the mike stands, Fouché gave McCoy the thumbs up. McCoy stood, put on headphones and bopped his head to a beat. He closed his eyes, took a deep breath and started to rap.

At the back of the room, Robinson bopped along, smiling.

“This is it,” he whispered to himself. “This is it.”

Twitter: @traceylien

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.