Paul Ryan’s idea to cover preexisting conditions via high-risk pools is a scam. Here’s why.

In yet another attempt to show that Republicans can be just as serious about healthcare reforms as Democrats, House Speaker Paul D. Ryan (R-Wis.) called Wednesday for eliminating the Affordable Care Act's guarantee of insurance for people with preexisting medical conditions.

Ryan didn't advocate cutting off these people entirely, but instead moving them into state high-risk pools that would subsidize their coverage. Taking them out of the general insurance population would "dramatically lower the price for everybody else" -- presumably everyone who was healthy. Speaking to students at Georgetown University, Ryan implied that this would be no big deal, because "less than 10% of people under 65 are what we call people with preexisting conditions, who are really kind of uninsurable."

You could almost invite some of these pools over for dinner. They're really dinky. There are only six that have more than 10,000 enrollees.

— Georgetown University health policy expert Karen Pollitz, describing high-risk pools in 2009

A couple of points about this. First, Ryan's estimate of the population with preexisting conditions is wildly low. Second, high-risk pools aren't a new idea. They're an old idea that was tried by 35 states before the enactment of Obamacare made them unnecessary. And they were massive failures.

Put these facts together, and what you have is a scam.

Mother Jones blogger Kevin Drum observes that Republican love to portray high-risk pools as "some kind of bold, new, free-market alternative to Obamacare." His judgment: "They aren't. They've been around forever and everyone knows they don't work."

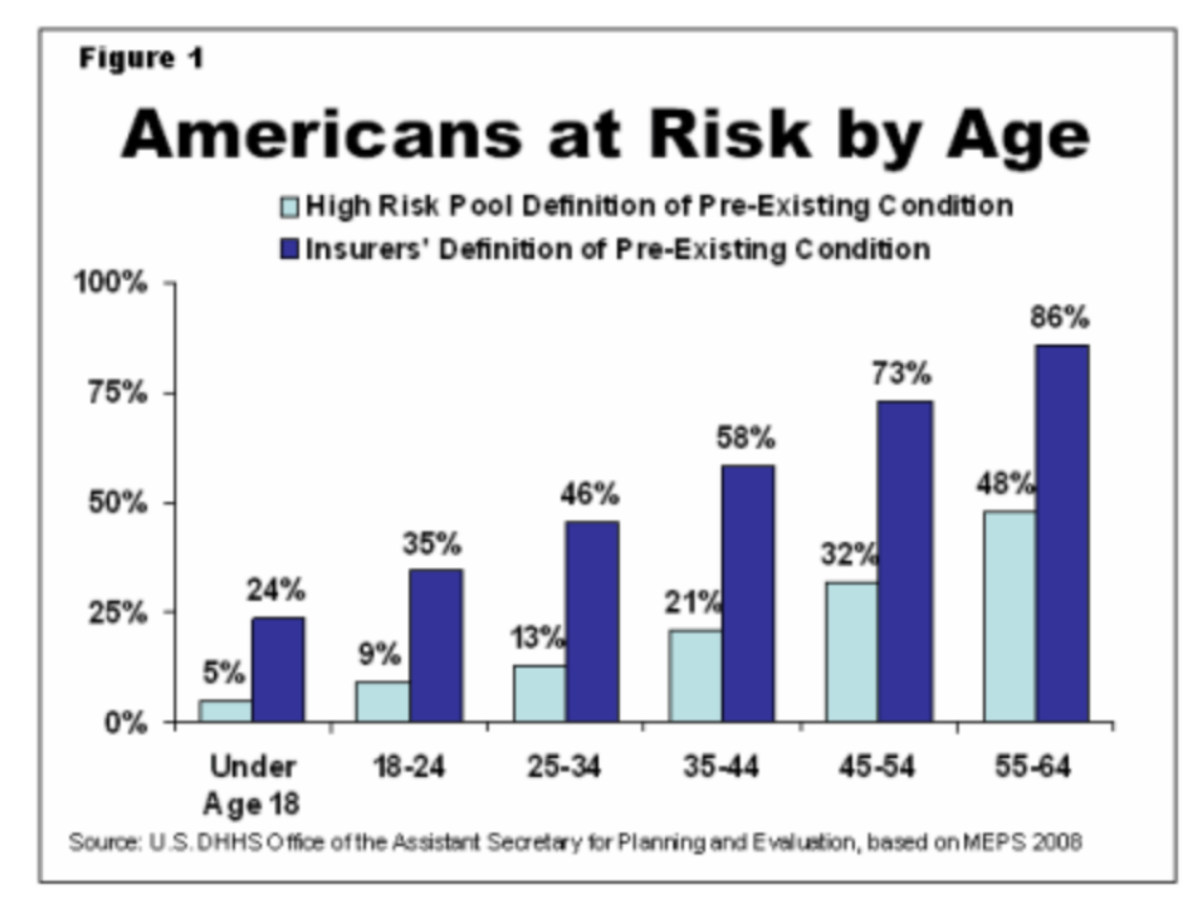

Let's start with Ryan's estimate of the affected population. Studies dating from before the ACA tended to place the figure much higher. The Department of Health and Human Services estimated in 2011 that 50 million to 129 million Americans under 65, or 19% to 50%, had some kind of preexisting condition and up to 20% of them were uninsured. The ratio rose sharply with age, so that as many as 86% of those aged 55 to 64 were at risk of being denied insurance because of their medical condition. In 2012, FamiliesUSA came up with a lower but still significant estimate: Nearly 25% of all Americans under 65 could be denied coverage without the ACA protections, the group said. They found that nearly 20% of those aged 18 to 24 had a "diagnosed significant preexisting condition." The figure rose to 50% of those 55 to 64.

It's important to note that preexisting conditions didn't always lead to denial of insurance. Often they led to higher rates, sometimes so high they made insurance unaffordable for those needing it most.

Recognizing that this had become a significant public health problem, dozens of states established high-risk pools to take these troublesome applicants off the insurance industry's hands. The programs universally were failures, leaving millions of residents without affordable coverage.

As health economist Austin Frakt has observed, by 2000, high-risk pool enrollment came to only 8% of the uninsurable population nationally, ranging by state from 1% to 54%. The problem was inadequate funding, which prompted states either to place caps on enrollments or saddle members with sky-high premiums. "We estimated that high-risk pool premiums were above 25% of family income for 29% of the medically uninsurable population," Frakt wrote. "That is, even when high-risk pool enrollment was possible, for a large minority of medically uninsurable individuals, it was unaffordable."

California's pool, the Major Risk Medical Insurance Program, or "MR. MIP," illustrated the problem. In 1990, when the program began with a $30-million budget funded by tobacco taxes, that was sufficient to enroll only 10,000 of the estimated 300,000 Californians who qualified. In 2009, enrollment was cut back to 7,100. Premiums were set as much as 37% higher than market rates for individual policies. The plans came with annual caps of $75,000 in benefits, not enough to cover treatments for some major diseases.

Nationwide, enrollment in state pools was so meager that "you could almost invite some of these pools over for dinner," Georgetown University health policy expert Karen Pollitz has reported. "They're really dinky. There are only six that have more than 10,000 enrollees."

Would high-risk pools fare any better today? It's doubtful. Ryan's apparent effort to low-ball the potential enrollment indicates that he and his colleagues are utterly unprepared to accept the cost of segregating the medically uninsurable in their own coverage pool. Like every program for the economically or socially needy, a federally-funded high-risk program would be first on the chopping block every time a House or Senate committee decided that government needed to shrink.

Keep in mind that conservative economist James Capretta estimated in 2010 that a high-risk program would need $15 billion to $20 billion a year to cover 4 million enrollees -- and he was in favor of the idea. And that as recently as last year Ryan, as House Budget Committee chairman, was pushing to cut $12.5 billion a year from the food stamp program, in part by turning it over to the states as a block-grant program. There lies the future of protection for those with preexisting conditions under Ryan's scheme. It's all about cost-cutting, pure and simple. As an alternative to Obamacare's flat outlawing of such exclusions, it won't wash.

Keep up to date with Michael Hiltzik. Follow @hiltzikm on Twitter, see his Facebook page, or email michael.hiltzik@latimes.com.