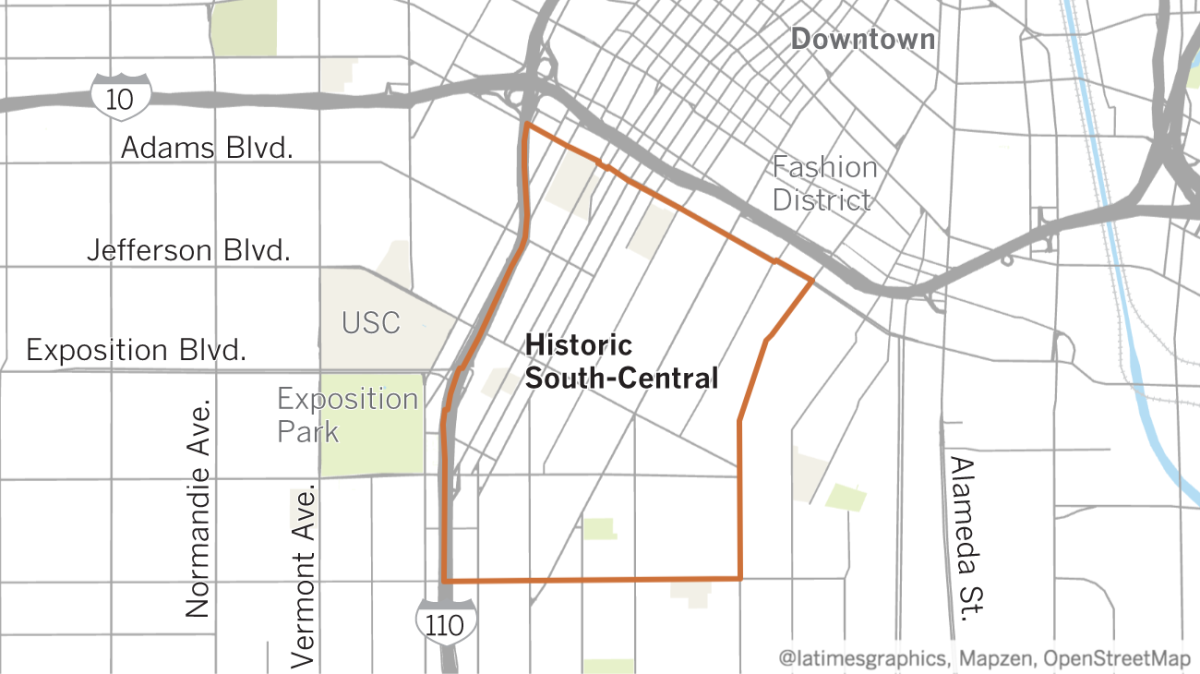

Neighborhood Spotlight: Historic South-Central looks toward growth in several directions

From the late 1800s to the 1910s, most newly arrived African American Angelenos took up residence in the historic center of the city, in an area near Spring Street known as the “Brick Block.”

There the community organized itself around the landholdings of former slave and L.A. pioneer Biddy Mason, who was one of the co-founders of the First AME church.

Businesses catering to newly arrived migrants sprang up, and a self-sufficient business district was soon thriving in the area.

As the neighborhood grew and prospered, a burgeoning African American middle class arose. The rise of drinking dens and and other disreputable establishments in what is current day skid row led the first businesses and residents to begin to leapfrog to the south and east to the more genteel environs of the nearby South Central Avenue corridor.

By 1915, the California Eagle, the preeminent African American newspaper of the time, was already calling the neighborhood along Central Avenue the “Black belt of the city.” The neighborhood’s proximity to downtown job centers, affordable single-family homes and L.A.’s extensive streetcar service drew an influx of new residents from other parts of the city and from the South.

It was in the 1940s, however that L.A.’s version of the Great Migration began in earnest, as African Americans from across the country headed west, drawn by jobs created by the war-driven manufacturing boom. Central Avenue was overwhelmed by the sheer number of new residents, as restrictive racial covenants kept the neighborhood boundaries from naturally expanding.

The concentration of African Americans from all backgrounds from Central Avenue and 41st Street all the way to the north in Little Tokyo (whose residents had been interned in detention camps following the outbreak of the war) created a critical mass of talent, energy and optimism that found its expression in one of America’s great cultural moments.

Jazz was suddenly everywhere, in the countless nightclubs that lined the neon-washed Central Avenue corridor, in recording studios around the city, and in movie theaters and radio stations across the country. In its heyday, the Central Avenue music scene was as influential as any in the country.

With the abolishment of L.A.’s most egregious forms of discriminatory housing laws in 1948, African Americans followed the general movement of the city’s population center westward, and Central Avenue’s predominance as the nexus of black culture in Los Angeles waned.

The nightclubs are now all gone, but the towering artistic achievements birthed in Historic South-Central live on.

Neighborhood highlights

Relative affordability: With many homes priced below $600,000, Historic South-Central provides much-needed home ownership opportunities to working-class Angelenos.

Location, location, location: USC and downtown are right next door, and the Blue Line and nearby freeways provide options for commuters to Long Beach and the Westside.

Neighborhood challenge

Left behind: The loss of middle-class residents to neighborhoods such as Baldwin Hills and Leimert Park devastated many local businesses, which have yet to fully recover.

Expert insight

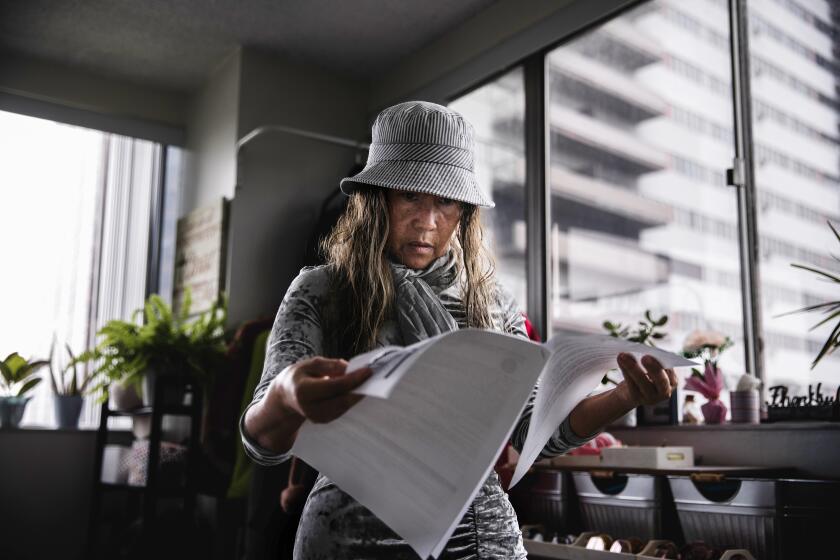

Cynthia Burts of Burts and Associates has been selling homes in Historic South-Central for a quarter of a century.

“The architecture here is mainly wood-frame stucco homes and 1920s brick buildings, many of which have outlived their useful lives,” Burts said.

She noted that although homelessness and poverty have plagued the area, things are looking up. The addition of the Metro line on the Washington Boulevard corridor has spurred growth, and a community plan recently adopted by the L.A. City Council hopes to revitalize the neighborhood.

“The city has new plans that seek to reward builders with incentives on the kinds of projects that residents and planners want to see more of,” Burts said. “Developers who build affordable housing may get away with less parking or more units to compensate for income they might have gained by building market-rate housing.”

She added that similar incentives would also be available for commercial development deals.

“My advice is to buy and take advantage of the lower pricing, lower interest rates and incentives offered to developers,” Burts said.

Market snapshot

In the 90011 ZIP Code, based on 14 sales, the median sales price for single-family homes in October was $371,000, up 12.5% year over year, according to CoreLogic.

Report card

Of the 13 public schools within the Historic South-Central boundaries, Ricardo Lizarraga Elementary fared the best in the 2013 Academic Performance Index with a score of 783. Other highlights include Quincy Jones Elementary, which scored 782, and Trinity Street Elementary, which scored 760.

The only public high school in the boundaries, Santee Education Complex, scored 636.

Times staff writer Jack Flemming contributed to this report.

MORE FROM HOT PROPERTY

Eddie Van Halen’s former home in Beverly Hills is hot for a sale

Lakers owner Jeanie Buss lands a new home court in Playa Vista

Spanish classic in Beverly Hills was once home to ‘Singin’ in the Rain’ lyricist