How a $1.3-billion, 21-year study of U.S. children’s health fell to pieces

The National Children’s Study was launched with a fanfare of expectation and ambition in 2000. The idea was to follow 100,000 American children from the pre-natal stage to age 21, collecting an unprecedented volume of data on “environmental influences (including physical, chemical, biological, and psychosocial) on children’s health and development,” in the words of the enabling federal legislation, the Children’s Health Act. As Science Magazine reported, it was the largest and most complex longitudinal study of its kind ever planned in the United States.

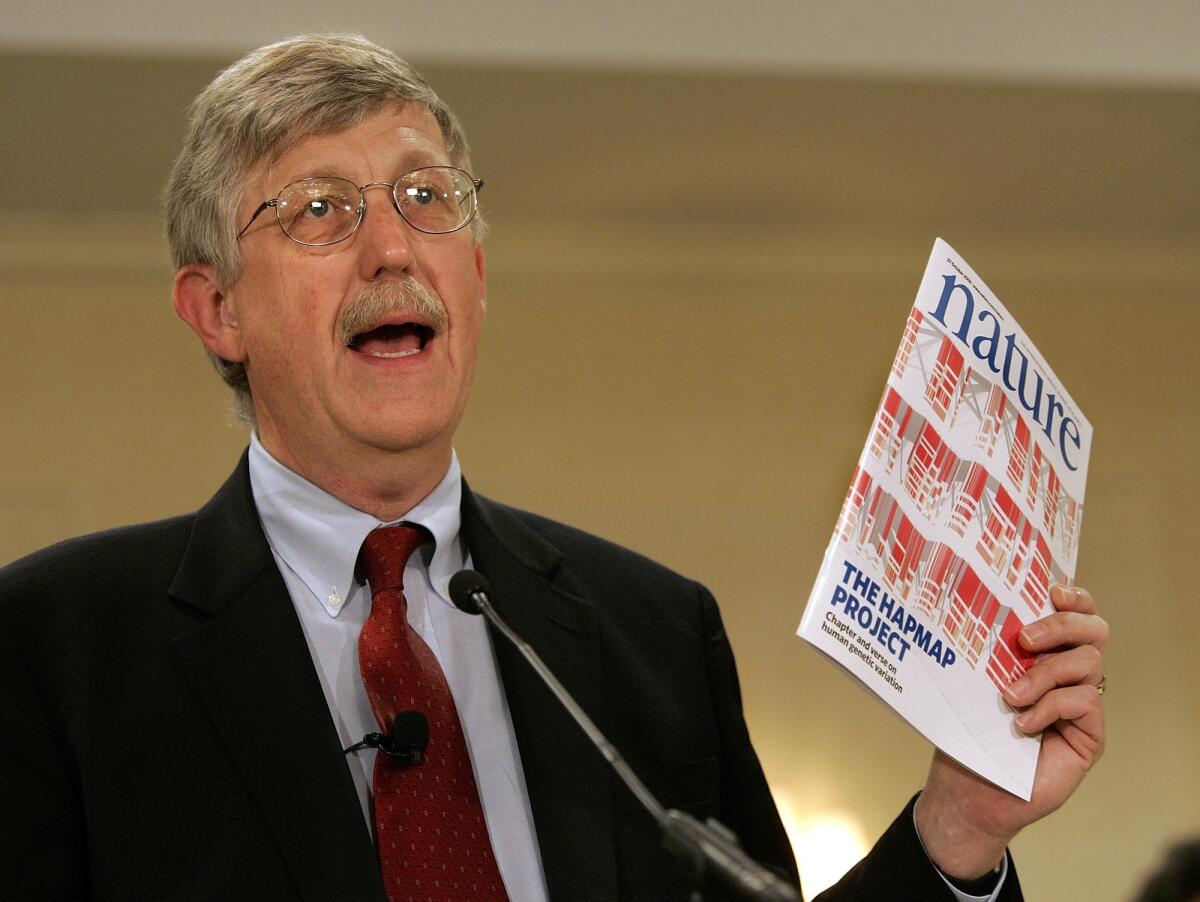

Today, after 14 years and the allocation of $1.3 billion to the task, it’s dead. On Dec. 12, National Institutes of Health Director Francis Collins ordered the study shut down after an advisory committee reported that it was “not feasible.” Despite that spending, the study itself never got off the ground; what was being done was a pilot program--a “vanguard study”--that enrolled 5,700 children starting in 2007. As for the $1.3 billion, the advisory committee report says that “the impact of this funding is unclear.”

What happened?

Almost from the start, the project was beset with poor management, poor planning and confused goals. It didn’t help that the state of research into many of the target factors was rapidly evolving. The initial plan was to recruit participants by knocking on doors of homes with pregnant women in 105 counties across the land--urban apartments, farmhouses, suburban split-levels--in an effort to produce a statistical cross-section of American upbringing.

A 2012 article in Nature described the data-collection process at a farm family’s home in Granite Falls, Minn.: Even before the family’s child, Brett, was born, “two fieldworkers... had spent hours in her home collecting, among other things, dust, air, water and toenail clippings from the parents to be. The same researchers would continue to visit and monitor Brett at regular intervals, becoming a fixture in the family’s life.”

But maintaining a core of dedicated fieldworkers was cumbersome and costly; in 2009, the cost estimate more than doubled to $6.9 billion, and nasty questions were being raised in Congress. The decision was made to turn over recruitment and field surveys to a cadre of outside consultants, which left families in the vanguard study feeling abandoned and misled. Nevertheless, by 2014, the budget was looking more like $30 billion.

Studies of the program were conducted by the National Academy of Sciences in 2008 and 2014, at the request of the NIH; finally, an NIH advisory committee led by Russ Altman and Philip Pizzo of Stanford University reviewed the National Academy studies, leading to the recommendation Collins has now followed.

The advisory committee endorsed the overall goal of understanding environmental factors in child health and development. But it found that “the NCS, as currently outlined, is not feasible.” Among other factors, the NCS statistical design was “overly complex, and the study design remains incomplete even after years of effort”--in fact, developing a “fully operational” research protocol was as much as two years away, even though recruitment for the full-scale study was to begin in 2015.

The NCS management, the committee found, was “not well suited to the tasks inherent in such a study,” and hamstrung by its oversight by multiple committees from different agencies. The research team was light on epidemiological expertise, which made it a stranger to “best practices for large longitudinal studies.”

As perhaps the final nail in the coffin, the NCS was designed and launched “at a time when NIH budgets were increasing.” That’s no longer the case; as it happens, just as pressure has risen for low-cost recruitment and data collection, so have the technologies to do so--social media, electronic medical records, and other initiatives that didn’t exist 14 years ago. But the NCS wasn’t flexible enough to take advantage of the new opportunities.

“There is little doubt,” the NIH committee concluded, “that elucidating the interactions and impact of environmental, genetic, behavioral, and societal factors in child development is enormously important, and could lead to major improvements in child, adolescent, and indeed long term adult health.”

But if this isn’t to be done via the NCS, then how? That may be the saddest question of all, because resurrecting the study seems unlikely. NIH officials, in letters to the vanguard study families, assured them that “all of the valuable information and specimens that you and your family have contributed will be stored and made available to scientists to further our understanding about environment and health...for many years to come.” But there won’t be more collections. A study that once was expected to create a 21-year database of 100,000 children will end at less than seven years and 5,000 children.

The year-end budget just passed by Congress allows the NIH to reallocate whatever money is left in the NCS budget to related activities, whatever they are. But the effect of that disbursement will be to render the NCS null and void. The goal was sound, but the opportunity lost, almost certainly forever.

Keep up to date with the Economy Hub. Follow @hiltzikm on Twitter, see our Facebook page, or email mhiltzik@latimes.com.