Prescription for pampering

Krista DAVIS is a 34-year-old self-confessed medical spa addict.

Every few weeks, she indulges herself at her favorite medical spa, Sherman Oaks-based Blue. On a typical day, she runs up a tab of $980 as she moves from manicure to pedicure, to underarm and leg laser hair removal, to Botox and to microdermabrasion, in which mineral crystals are used to sandblast the skin.

It’s not cheap, but the Porter Ranch woman, a former aesthetician who now sells skin-care products, feels she gets more bang for her buck at Blue Medical Beauty Spa than she would at a traditional spa, because pampering and “aggressive” medically based beauty treatments are offered under one roof.

And it’s under a roof that is far more appealing than an old-fashioned, green-walled doctor’s office. Davis loves Blue’s futuristic décor, including the big flat-screen televisions, the well-cushioned chairs, the sheepskin rugs and the lush, dark-blue velour curtains. Says Davis, “People don’t want to go into a cold setting. They want more inviting settings.”

Consumers such as Davis have turned medical spas into the hottest segment of the $11.1-billion-a-year spa industry. “The spa and the medical world are combining in a new entity,” says Eric Light, president of the International Medical Spa Assn. Dermatologists, plastic surgeons and other medical professionals, including dentists and gynecologists, are either opening their own spas or signing on as consultants at existing ones.

But consumer advocates and others worry that regulation of medical spas has not kept up with the industry’s growth. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration oversees the safety of the machines and skin-care products used at medical day spas. But it is up to each state to figure out which practitioners can administer the treatments safely.

That job falls mostly to state skin-care and medical licensing boards. But because of explosive growth in the medical spa industry and rapidly changing treatments, those boards cannot regulate medical spas effectively, says industry marketing analyst Nancy Griffin. “As a consumer, you can’t count on your state boards to protect you.”

Griffin recommends that consumers be in buyer-beware mode when they go to medical spas, because even treatments that are touted as being state of the art can damage the body if performed incorrectly.

Medical beauty treatments can also be pricier than the services at your regular old-fashioned spa. But proponents stress that the prescription-strength products and treatments offered at medical spas are more effective than the body and skin care available at a traditional spa.

Charlie Sheridan, director of the Institute in Marina Del Rey, a medical spa that offers everything from “lipstick to liposuction,” says that because the facility’s medical director is a plastic surgeon, it can offer pharmaceutical-grade “cosmeceuticals.” These prescription products, says Sheridan, are more effective than the skin products available over the counter.

In addition, the Institute offers treatments such as Botox injections; photo facials that use intense light to combat a variety of imperfections, including large pores and age spots; and a face-lift that uses radio frequency energy. Sheridan stresses that these treatments cannot replace surgery, but that “with advanced medical technology, it is quite amazing what can be done. With injectable fillers, peel products and lasers, we can offer amazing improvement.”

Manhattan’s Juva MediSpa also touts its “physician-formulated spa treatments” that “far surpass the normal spa techniques.” For $135, it offers a 70-minute anti-aging “medical facial” that includes “clinically proven 5-FU [5-fluorouracil, an anti-cancer drug used topically] to remove sun-damaged cells.” Says dermatologist Bruce Katz, founder of Juva: “We use medicine in our facials and our body treatments. We put antioxidants into our spa oils.”

No matter how “medical” beauty treatments are, insurance companies won’t pay for them, which makes for a highly motivated clientele. They’re “people who are serious about getting their skin into the most ideal physical and aesthetic condition,” says Sheridan. “You have a client population of serious buyers, so to speak.”

Cash-based medical spas also provide freedom for doctors who say they are tired of being second-guessed and under-reimbursed by insurance companies. A want ad that appeared recently on the message board of eSTART.com sought “entrepreneurially minded” doctors to work or own a medical spa in New Jersey and New York. The listing, posted by Mobius Development Group, which sells medical spa franchises and consulting services to doctors, stresses “no more hassles with insurance companies.”

Dermatologist Mitchel Goldman says chucking the insurance companies he “hates” has enabled him to practice more patient-friendly medicine.

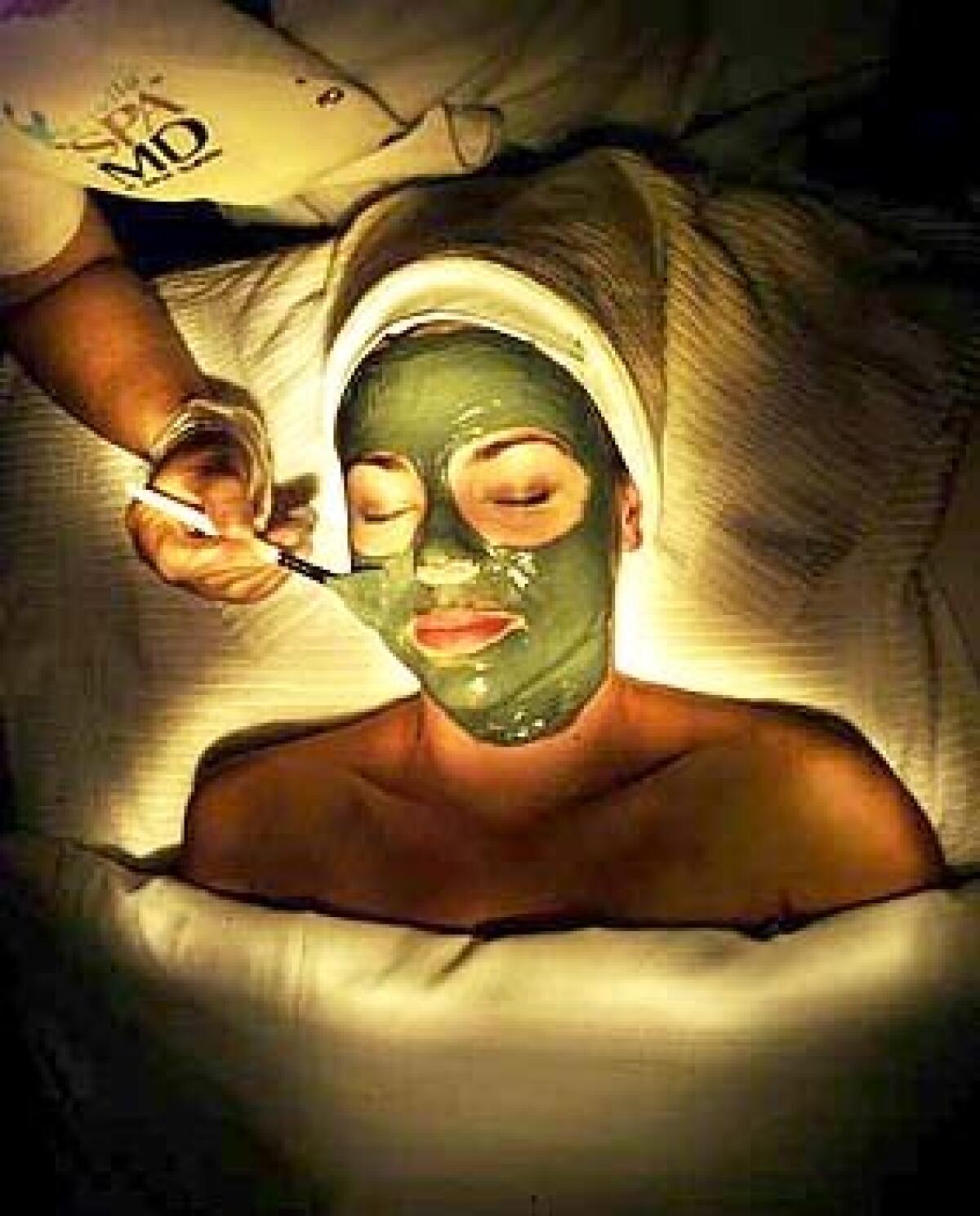

At Goldman’s 15,000-square-foot Spa MD in La Jolla, there are soothing waterfalls designed using feng shui and bamboo floors, but there is no waiting room with “20 stupid chairs,” as he puts it. Instead, Spa MD features a concierge who directs patients to four nicely upholstered chairs in an area called a reception room. “No one waits. I give people time.”

When Goldman was accepting insurance, he packed in 40 to 50 patients a day. “It was like working in a mill.” Now, says Goldman, he sees 15 to 20 patients a day. “I’m not going on volume anymore. I’m going on quality.”

Doctors can avoid insurance companies at medical spas, but they cannot avoid pricey malpractice insurance coverage. With five full-time and three part-time physicians, 18 nurses, one physician’s assistant and one nurse practitioner, Goldman, for example, pays $250,000 a year in malpractice insurance.

That’s not surprising, given that there have been a number of lawsuits against spas that employ physicians.

In 2001, investment banker Kim McMillon filed a $125-million lawsuit against the upscale Manhattan-based Greenhouse Day Spa (now under new management), a dermatologist who worked there as a consultant and the cosmetologist who treated her. McMillon, who is African American, alleged she received first- and second-degree burns when the cosmetologist, who she said did not know how to use a laser for hair removal on dark skin, botched the job.

According to the complaint, McMillon halted the treatment halfway through because “I could smell the burning. I could feel my face on fire.” McMillon also alleges that the dermatologist incorrectly prescribed a bleaching agent for her burns. The defendants have denied the allegations since the lawsuit was filed. The case is expected to go to trial in the next six months.

McMillon’s attorney, Susan Karten, says the case “is really a wake-up call for states around this country” to require that laser hair removal be done by professionals with the proper credentials. Everyone from gynecologists to cosmetologists is performing the procedures, says Karten: “It’s a booming phenomenon. Everyone thinks they’re an expert.”

Regulatory confusion

Would-BE experts are taking advantage of the hodgepodge of regulations that cover laser hair removal and other medical spa procedures.Some states, for example, require physicians to perform laser hair removal. Others allow physicians to delegate the procedure to medical and nonmedical licensed practitioners as long as they supervise them. A few states have not yet specifically regulated laser hair removal. “It’s kind of the wild, wild West,” says Dr. Jay Calvert, a UC Irvine plastic surgeon who will be teaching a new course this fall about spas.

The confused regulatory picture means that consumers can become guinea pigs unless they are careful. A weekend training course offered by a company that manufactures lasers does not make a person qualified to remove someone’s hair, says Calvert. Before you let someone point a laser at you, make sure you find out how much training and experience they have operating lasers, says Calvert. “You don’t want to be part of someone’s learning curve.”

Some in the medical spa industry are so concerned about lax and conflicting regulations that they are pushing for national standards. Katz says the McMillon case was one of the motivating factors behind his decision to form the nonprofit Medical Spa Society, whose mission is to “promote standards of excellence.”

“We don’t want a few bad apples to start causing havoc by burning faces,” says Katz.

Burned faces aren’t the only side effect of botched aesthetic treatments. When the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery queried its members in 2002, 40% of respondents reported seeing more patients who had received substandard care from nonphysicians. Laser treatments topped the list of botched procedures, but the dermatologists also cited chemical peels, acne therapy and misdiagnosis or delayed treatment of skin cancers and rosacea.

According to Dr. Roy Geronemus, a Manhattan dermatologist and former president of the dermatologic society: “We’re seeing a lot of scars, superficial burns and changes in pigmentation.”

Consumers can sue when they believe they get substandard treatment, just as McMillon did, but most such cases do not end up in court. Some victims shy away from revealing that they received aesthetic treatments. And many lawyers believe that jurors — especially those more concerned about grocery bills and basic medical care than hair and wrinkle-free skin — will have little sympathy for the alleged victims of botched elective procedures.

Although much of the focus on preventing shoddy treatment has been on nonphysicians, industry insiders stress that undertrained doctors can also provide substandard treatment. Susan S. Warfield, chief executive of Paramedical Consultants Inc., a New Jersey-based spa industry consulting firm, warns: “Don’t think that because you’re going to Dr. Wonderful’s medical spa, the aesthetic treatments you’re going to be getting are better than Sally’s salon and spa down the street.”

Goldman agrees. He says consumers should be pushy when asking what type of doctor is involved with the spa. Otherwise, “The doctor could be a proctologist who doesn’t know what skin is. All you have to do is have an MD after your name and you can do anything you want.”

In addition, consumers need to ask how many hours a week the doctor is at the medical spa. California, for example, allows licensed physician’s assistants, nurses and nurse practitioners to perform cosmetic medical procedures, including Botox injections, laser hair removal and intense light facials, if they operate under the supervision of a physician. But Goldman says medical supervision can mean that the doctor is licensed in California but lives in Utah and is at the spa sporadically. Consumers should ask: “Where is the beef? Where is the doctor?”

Karten notes that the Greenhouse Day Spa, where McMillon got her treatment, for example, “billed themselves as having medical oversight.” But Karten stresses, “The question is, is that enough?”

Recently, the California Department of Corporations ordered the Los Angeles-based medical spa company HealthWest to “stop offering to sell franchises and licenses.” According to the department, HealthWest was advertising that potential franchisees could “own a prestigious business in the medical industry without a medical background.”

You don’t have to have a medical background to own a spa, but the Department of Corporations says HealthWest failed to get approval before selling franchises and failed to disclose to the franchisees that physician supervision was necessary for some treatments.

High profits

None of the regulatory loopholes in the medical spa business is likely to put a crimp in its growth, because medical procedures generate high profit for spas. “Laser hair removal as well as photo facials spell higher profit for a medical spa, as opposed to doing wraps and massages,” says Calvert.For doctors, adding spa services can significantly expand their practice, which is why the want ad at eSTART.com touted “increased financial upside,” in addition to insurance-free living. At Spa MD, for example, one of four customers who come in for a spa-side treatment eventually wind up as patients on the medical side, perhaps for a treatment for varicose veins.

Medical spas clearly offer a winning business model, but even boosters such as Light say consumers should use common sense when indulging in treatments. “Be realistic about the outcome. Anybody who promises they’re going to cure your cellulite or remove every wrinkle on your face, go the opposite way.”

Light even recommends that Americans take a more “holistic, European” approach to the aging process: “There’s nothing wrong with a wrinkle or two. We used to call them signs of wisdom.”

Nonetheless, spa-goers seem bent on wrinkle-free skin. And that is precisely why industry analysts predict a blemish-free future for medical spa profits.