Mexico earthquake crumbles concrete buildings, sending deadly warning to California

A building that survived the last earthquake will not necessarily survive the next one. (Sept. 21, 2017)

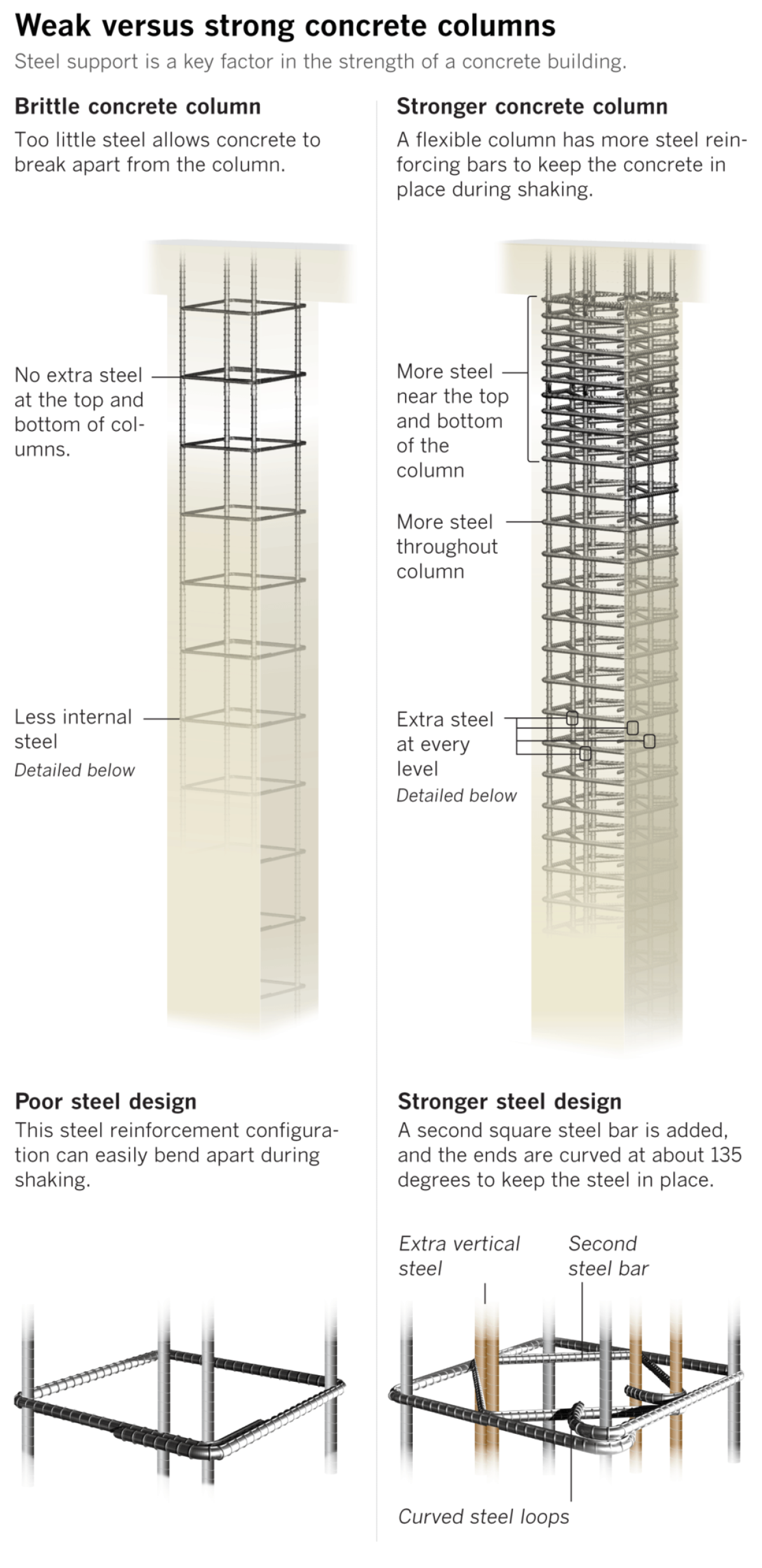

Seismic safety experts long have warned that brittle concrete frame buildings pose a particularly deadly risk during a major earthquake.

But a horrifying video taken during this week’s magnitude 7.1 Mexico quake may do more to highlight the risk than years of reports and studies.

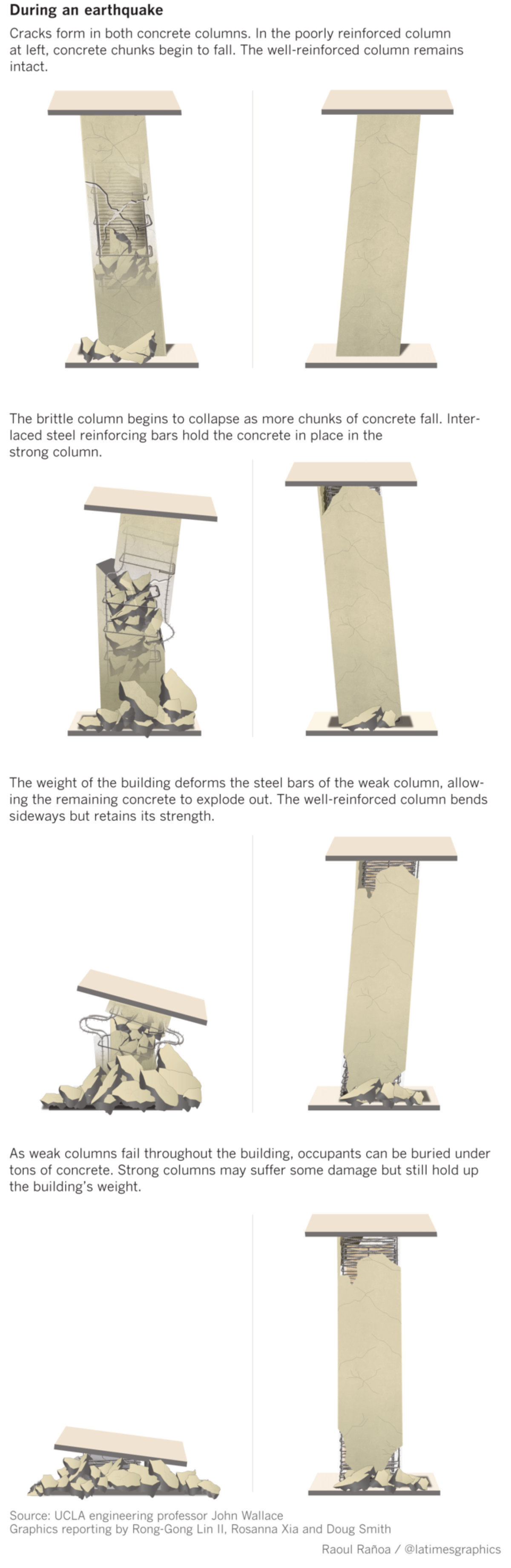

In it, sirens blare, utility poles sway. Then in the background, a building wobbles. Concrete starts falling out of a ground-floor column. Then the columns flex, and the upper floors come crashing down, sinking into a cloud of dust.

“¡Dios mío! ¡Dios mío!” a woman is heard saying. “My God! My God!”

The crumbled Enrique Rebsamen school in Mexico City — a three-story structure where at least 25 died, including 21 students — was made of concrete, as were many other structures that fell to the ground.

While they may be stout and muscular in appearance, concrete buildings without a robust level of steel reinforcement can see their columns peel off in chunks and then explode when exposed to violent side-to-side shaking.

Collapses of concrete buildings have been documented worldwide for decades.

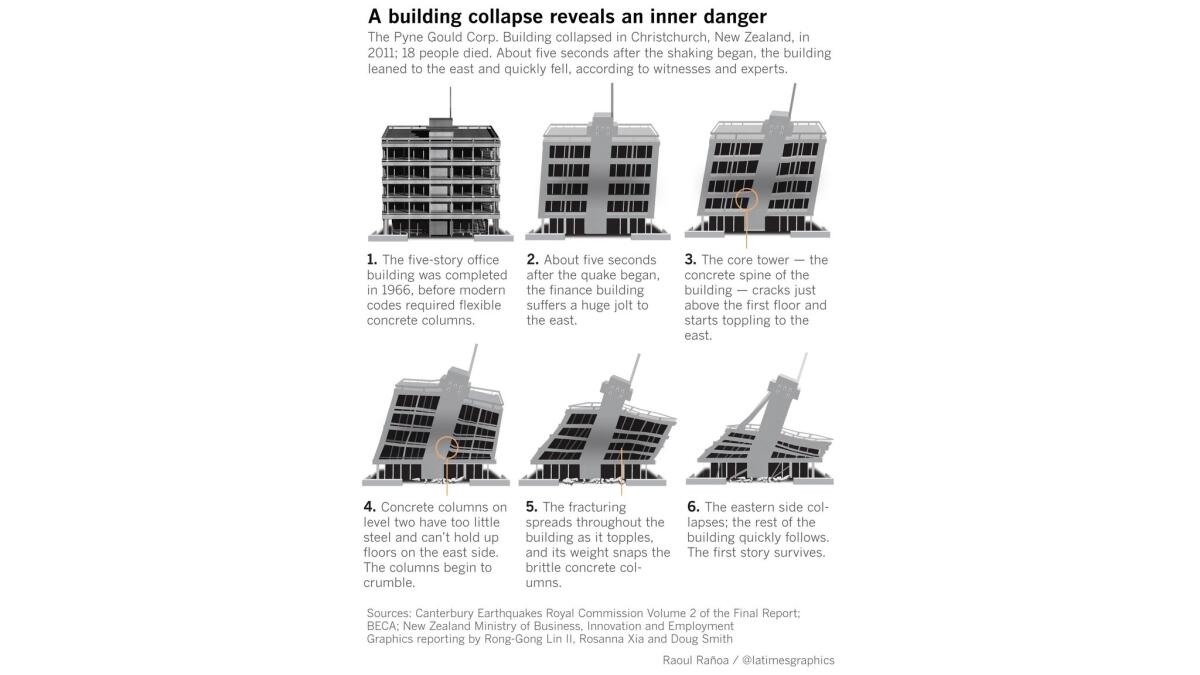

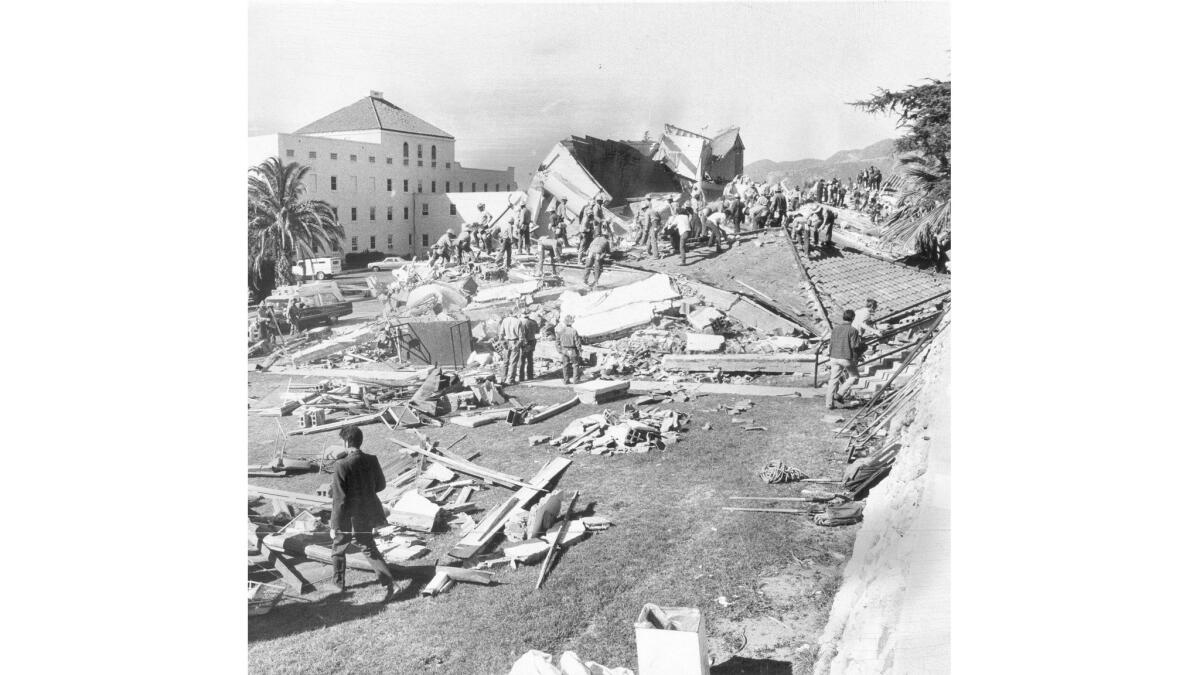

In Los Angeles, dozens died when concrete structures tumbled in the 1971 magnitude 6.1 Sylmar earthquake. Several who perished were on a newly built hospital campus. And when two concrete office towers collapsed in 2011 during a 6.3 temblor in Christchurch, New Zealand, the 133 people who died accounted for more than 70% of the final toll.

After the Sylmar quake, officials quickly updated building requirements to add more steel reinforcement to new concrete buildings. But there was no systematic effort by many governments around the world to address the defect in existing concrete buildings.

‘it’s such a tremendous impact’

Mexico quake shows what seismic experts have long warned

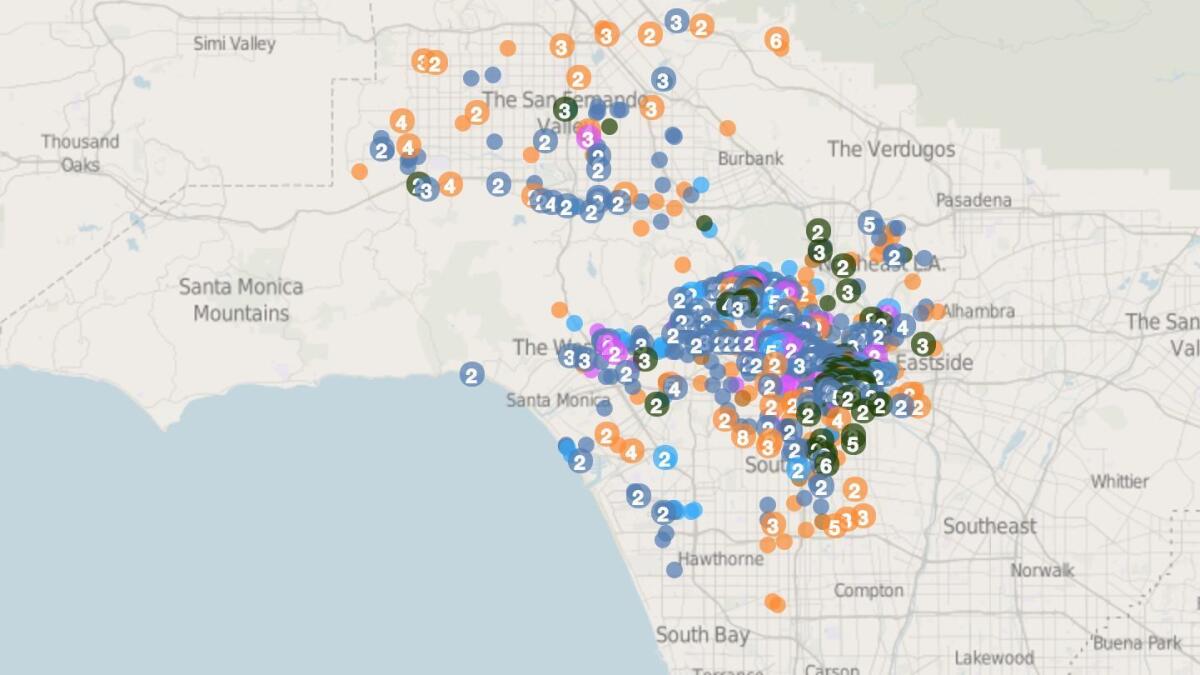

Concrete buildings dot the California landscape, a popular form of construction during the postwar boom years.

But cities are just now beginning to grapple with how to make these buildings safer.

In 2015, Los Angeles Mayor

The law requires that once owners are given an order to evaluate a building, they will have 25 years to retrofit it if a study determines the structure is indeed vulnerable. City officials are in the process of identifying buildings that would be subject to the law.

A couple of other cities have done the same.

Santa Monica earlier this year published a list of vulnerable buildings — concrete, steel and wood-frame apartments — and enacted a new law requiring them to be evaluated and retrofitted if found to be vulnerable. West Hollywood also has enacted retrofit laws for the same classes of buildings.

Garcetti and seismic safety experts say the catastrophic images from Mexico this week will raise awareness of the dangers.

“Any building owner who thinks they should sit back and relax for the next 20 years should view that video. And let’s figure out a way to get to work now,” Garcetti said in an interview. “What’s more expensive? The loss of your entire property — let alone the loss of lives — or the investment in making sure that no earthquake of that size will destroy your building or kill anyone?”

The collapsed school is a case in point. California-based structural engineers who looked at a Times photo of the school’s remains said the collapse was consistent with the failure of a brittle concrete building.

Structural engineer David Cocke, vice president of the Oakland-based Earthquake Engineering Research Institute, pointed out how a concrete column at the school can be seen broken in half — a clean break. He said there should have been more steel reinforcement in the concrete that would have allowed the column to bend when shaken, not break like a piece of chalk.

“When they break in half like that, then you’ve lost it all,” Cocke said.

Structural engineer Kit Miyamoto, a member of the California Seismic Safety Commission, said the photo “looked like the columns popped out of the building … there’s no adequate reinforcement. It’s exactly the problem of nonductile [brittle] concrete.”

And the video showing the concrete building collapsing, Miyamoto said, has “such a tremendous impact. Most people think that they are helpless, it’s too expensive to fix. That’s a myth. This video can defeat that myth. Evidence exists, people are dying and we know exactly what to do.”

“Actually being able to physically see the process — I think it’s incredibly effective. It explains what a lot of the issues are,” seismologist Lucy Jones said. “Concrete buildings seem sturdy … and being able to see directly why that’s not true has got to start.”

To be sure, some buildings in developing nations are not as well-engineered as some buildings in California, Cocke said. But “these buildings are not that dissimilar to some of our worst buildings. We’re going to have failures on some of our older, nonductile concrete buildings that can be catastrophic — when we have intense shaking.”

The video, Cocke said, also shows the threat of buildings with flimsy first stories, where relatively skinny columns hold up heavier upper floors. The so-called “soft-story” flaw is found in many California apartments, where the ground floor is built to house carports, garages or storefronts; flimsy supports can snap and collapse in shaking.

Other cities are looking at the issue.

Jones is now working with the Southern California Assn. of Governments to help cities come up with seismic retrofit legislation to propose to their elected leaders. Jones said Long Beach is looking to hire a consultant to create an inventory of seismically vulnerable buildings. And Ventura has directed its city staff to work with Jones and SCAG to develop an approach for unretrofitted brick buildings and wood apartment buildings with flimsy first stories.

PEOPLE DIE IN BUILDING COLLAPSES

The grim toll of concrete buildings

The brittle concrete defect gained considerable attention after the 1971 Sylmar earthquake caused the collapse of the newly constructed Olive View Medical Center.

Several other concrete structures came tumbling down in that earthquake, in which 52 people in all were killed as a result of concrete structure failure.

Brittle concrete buildings also collapsed in the magnitude 6.7 Northridge earthquake in 1994, including a Bullock’s department store and Kaiser Permanente medical office.

In addition to stabilizing concrete structures, efforts focused on other vulnerable buildings have shown signs of success.

Los Angeles’ 1981 law requiring retrofitting of 8,000 brick buildings saved lives: Although 60 people died in the Northridge quake, none of them were in brick structures. L.A. and a handful of other cities in California are now also requiring retrofits for apartment buildings with weak first stories.

Retrofitting concrete buildings is considered more costly. The fixes could cost $1 million or more per structure. Occupants may have to move out during the renovation at an additional cost.

Yet a seismic retrofit is a bargain compared with the cost of replacing a collapsed building, Miyamoto said, which will be unusable and unable to generate rental income for owners. “There is no excuse to not do it,” Miyamoto said. “It’s spending 5% to 10% of the replacement cost to address the seismic strengthening.”

‘We don’t really know what’s going to happen’

Sober lessons from Mexico

The experience in this week’s Mexico earthquake also illustrates another fact: Just because your home or workplace survived a previous earthquake doesn’t mean it will endure the next one.

A common sentiment in Los Angeles, as in Mexico City, was that buildings that survived past earthquakes were invulnerable to shaking. That’s wrong.

Despite several devastating quakes — in 1933 in Long Beach, 1971 in Sylmar and 1994 in Northridge — many vulnerable buildings constructed during Southern California’s rapid expansion in the 20th century simply have not had to face the intense shaking that scientists know can happen during an earthquake.

The last magnitude 7.8 quake that struck Southern California hit in 1857, long before the modern era of Los Angeles.

“I hear quite often: ‘Hey, we went through the 1994 Northridge earthquake. We’re OK.’ Well, that’s a false sense of security,” Miyamoto said. “This earthquake proved it. Doing well in one earthquake doesn’t mean you’ll do well in the next.”

At its closest point, the San Andreas fault is just 30 miles from downtown L.A. That closeness means the tallest skyscrapers in the nation’s second-largest city could be quite vulnerable during a megaquake.

A U.S. Geological Survey simulation co-written by Jones and published in 2008 said it was plausible that five steel high-rise buildings throughout Southern California — whether in downtown L.A., Orange County or San Bernardino — could come tumbling down should a magnitude 7.8 earthquake strike the San Andreas.

After the Northridge earthquake, a flaw was discovered in a common type of steel building that showed how the frame can fracture in an earthquake; Los Angeles and most other cities in California have not passed laws requiring retrofits to repair this design flaw. (Garcetti on Friday said L.A. building officials are studying Santa Monica’s new law passed this year requiring retrofits of steel buildings.)

“We don’t really know what’s going to happen to those really tall buildings. We’ve never put them through a really big earthquake,” Jones said.

Downtown L.A.’s shortest buildings also haven’t been tested with extreme shaking, Jones said. At no point in modern history has downtown Los Angeles endured the kind of intense shaking that the San Fernando Valley did during the Northridge quake.

“Your Northridge-type earthquake is about as bad as it gets for small buildings like a single-family house or a small apartment complex,” Jones said. But while places like Northridge and Chatsworth have endured what is close to the worst-case shaking, places a bit farther away — like Pasadena, Hollywood and downtown L.A. — have not.

“Even Santa Monica” has not, she said, despite the intensity of damage in that coastal city during the ’94 quake. “The reason there was so much damage there was because of how old the buildings are,” Jones said.

Different earthquakes will test different buildings.

A sharp magnitude 7 earthquake on an urban fault that runs through the L.A. metropolitan region — such as the Newport-Inglewood, Whittier or Sierra Madre faults — will test short buildings like no other earthquake in the modern era, Jones said.

Meanwhile, a magnitude 8 on the San Andreas fault likely will spare the worst from striking single-family homes in places farther from the fault, including the L.A. Basin. But the same megaquake could result in “collapses of high-rises at relatively large distances from the fault,” Jones said.

Miyamoto said L.A. is on the right track in retrofit policy, but should consider accelerating the deadline for retrofit requirement.

“We should go faster,” he said. “The earthquake will not wait for us.”

Twitter: @ronlin

UPDATES:

3:30 p.m.: This article was updated with a quote from Mayor Eric Garcetti.

This story was originally published at 11:15 a.m.

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.