Dorner mentor cracked case

It was nearing midnight when Terie Evans called police in Irvine with a hunch: An ex-Los Angeles police officer named Christopher Dorner might have killed a young Irvine woman and her fiance a few days earlier.

Evans, an LAPD sergeant who had trained Dorner, conceded that her theory was a long shot. But Dorner’s name had suddenly surfaced the day before in a strange phone call. And she knew he had a connection to the woman who had been killed. It seemed too much to dismiss as a coincidence.

It wouldn’t take long for Irvine detectives to realize just how valuable Evans’ tip was.

Before dawn they were looking into Dorner. An investigator uncovered a rambling manifesto Dorner allegedly posted online, in which he expressed fury over his firing years earlier and laid out his plan to exact revenge by killing officers he blamed for his downfall and their family members.

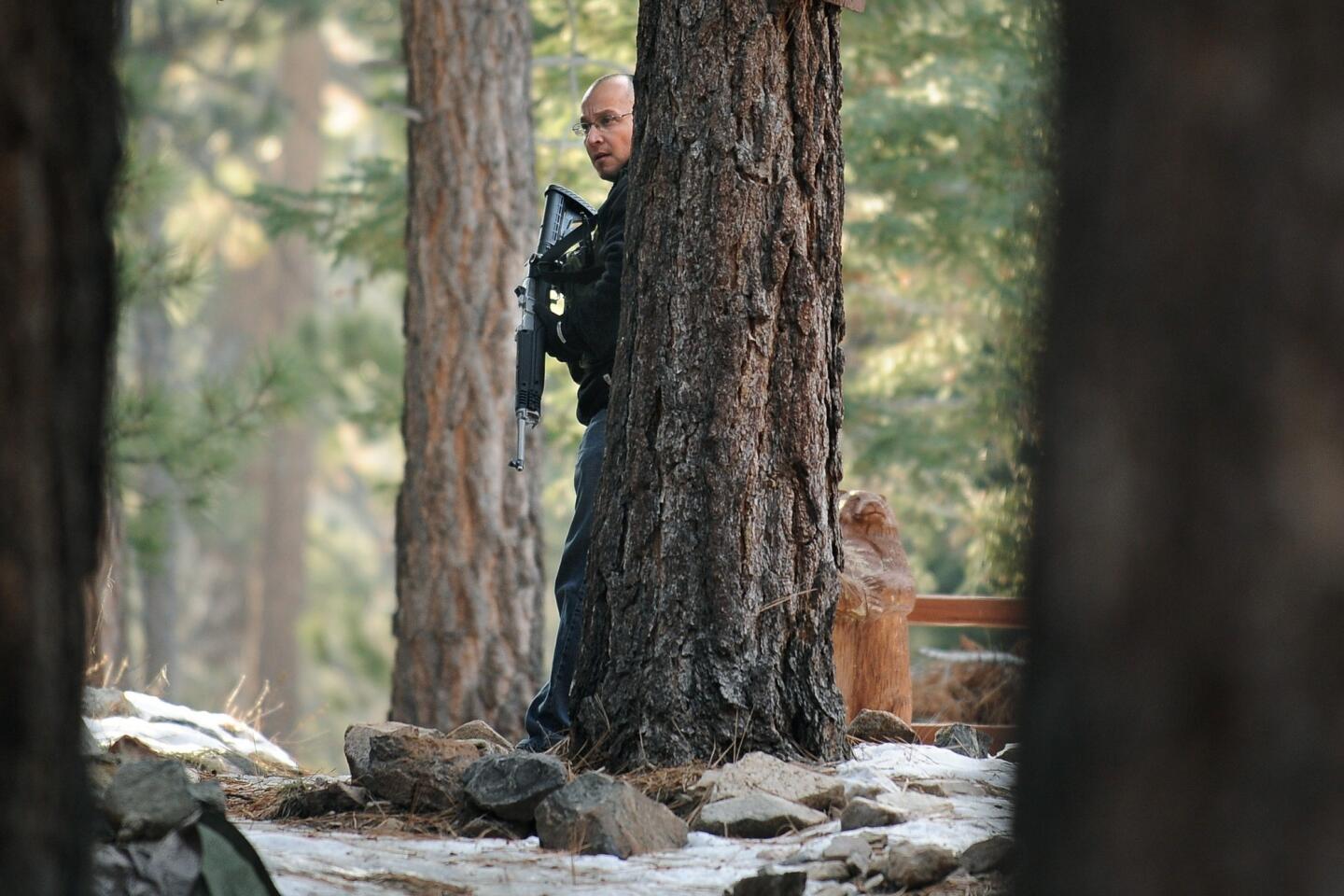

The discovery sent Evans and about 50 other LAPD officers and their families either into hiding or under the protection of heavily armed guards as a massive manhunt for Dorner unfolded across Southern California.

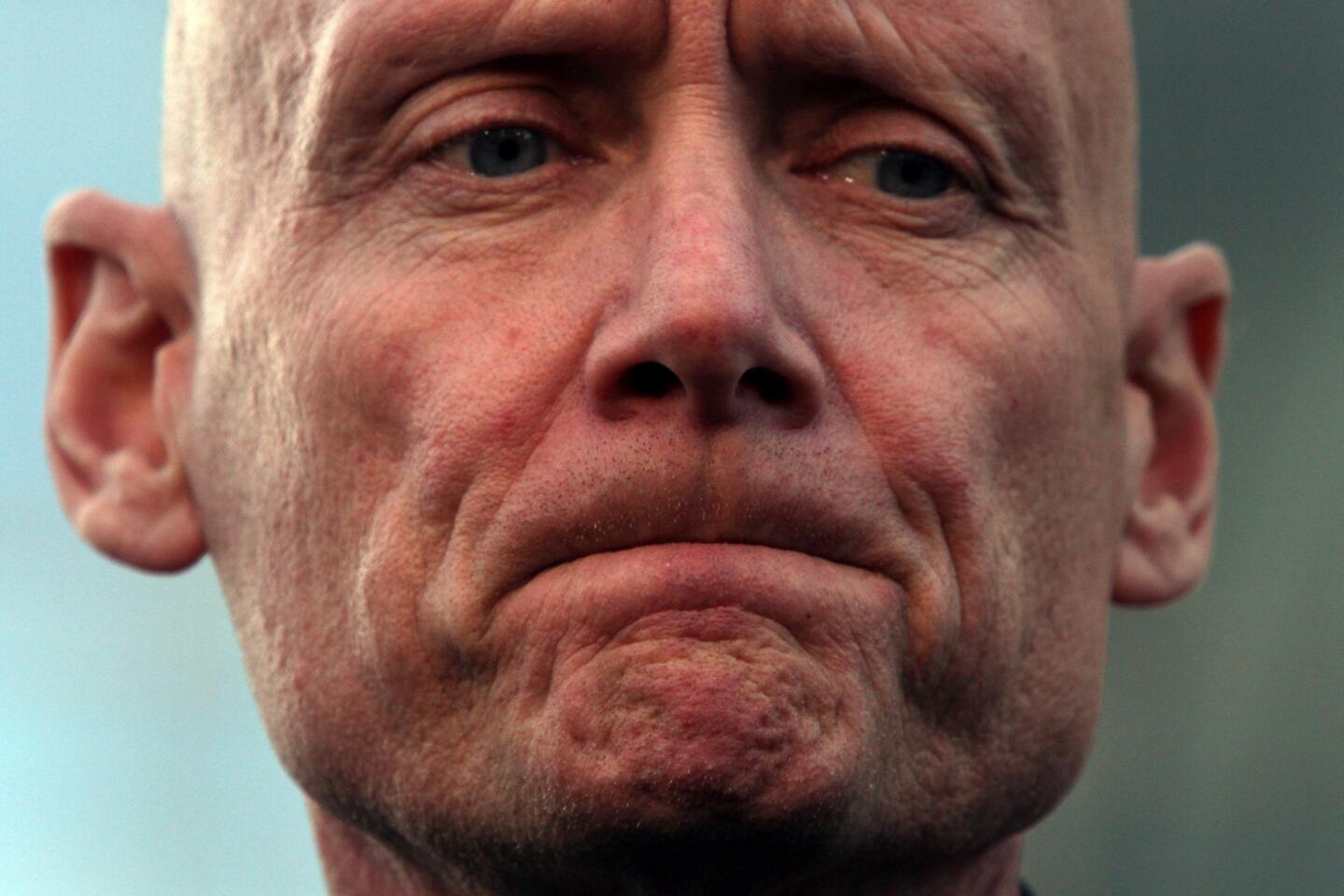

For the eight days that Dorner eluded capture, Evans remained silent and laid low, while Irvine and Los Angeles police officials kept secret her role in identifying the suspect. Evans had been Dorner’s training officer and was at the center of the incident that led to his dismissal from the force. Authorities worried it might enrage Dorner further if he knew she had once again played a lead role in determining his fate.

On Thursday, Evans spoke to The Times about what happened, and police confirmed her account. LAPD Chief Charlie Beck said he believes Evans’ actions saved lives, helping detectives identify Dorner before he carried out more surprise attacks.

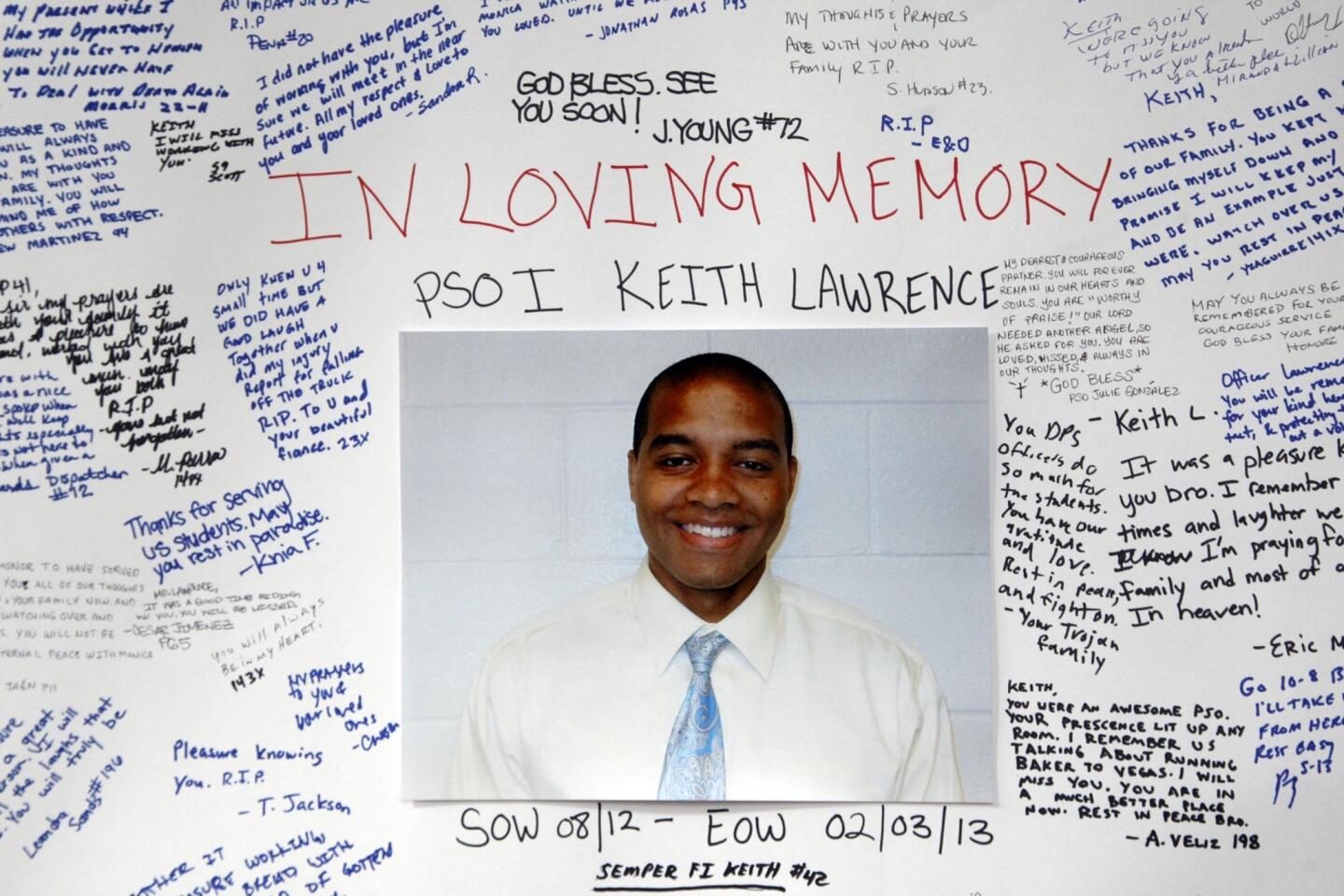

It began for Evans on Monday, Feb. 4 — the day after the bodies of Monica Quan and Keith Lawrence had been found riddled with bullets in their car. Evans, 47, received a message that an officer from a small department south of San Diego was trying to reach her. When she returned the call, the officer told her that he had found pieces of a large-sized police uniform, some ammunition and other items discarded in a dumpster that appeared to belong to an LAPD officer with the last name Dorner. Evans’ name and other items were written in a small notebook found with the other things. The officer asked: Did Evans know this guy Dorner?

She did know him. Several years earlier, Evans and Dorner, a rookie cop, had been partners. The pairing had ended badly when Dorner accused Evans of kicking a handcuffed man.

Evans denied the allegations and an investigation cleared the 18-year veteran of wrongdoing. LAPD officials went on to fire Dorner after concluding he had fabricated the story.

“Just hearing his name was enough to make me feel sick,” Evans said.

Evans hadn’t been able to shake the uneasy feeling when she went to work the following evening. Before beginning her night shift, she stopped in the police station’s parking lot to talk with some other officers. The conversation turned to the Irvine killings. Evans had heard about the case, but knew no details. The dead woman, one of the officers said, was the daughter of Randy Quan, a former LAPD captain-turned-lawyer who represented LAPD officers in disciplinary hearings when they ran afoul of the department.

The hair on the back of Evans’ neck stood up. Another wave of the shakiness she had felt on the phone washed over her. She struggled to make sense of her thoughts. Quan. Dorner. The belongings in the dumpster.

Through her night shift, a “nagging, sinking feeling” dogged her. “I have to call Irvine PD,” she recalled thinking.

“In my mind, it felt like such a long shot,” Evans said. “But my gut feeling made it a lot stronger than that. I just knew. Something told me that there was some kind of a connection.”

Evans called the Irvine Police Department and told a supervisor her theory: Quan had represented Dorner at his termination proceedings. What if Dorner had killed Quan’s daughter and her fiance as part of a vendetta and then tossed his belongings in the dumpster before escaping across the border to Mexico?

About 1 a.m., an Irvine detective called back and Evans repeated her suspicions. A few hours later, her shift ended and Evans went home to sleep. When she awoke, a message from another Irvine detective, left early that morning, was waiting for her. Investigators were pursuing her lead and were on their way to San Diego to examine Dorner’s belongings.

“At that point, I was absolutely sick,” Evans said. “I thought, ‘Oh my god, it really is him.’ I knew no one knew where he was ... I thought, ‘What am I going to do?’ At the time Mr. Dorner was terminated, I had a very uneasy feeling. I knew he was very upset and I had concerns that at some point he may try to contact me. So, this was just validating the bad feeling I carried with me for years. I was scared to death.”

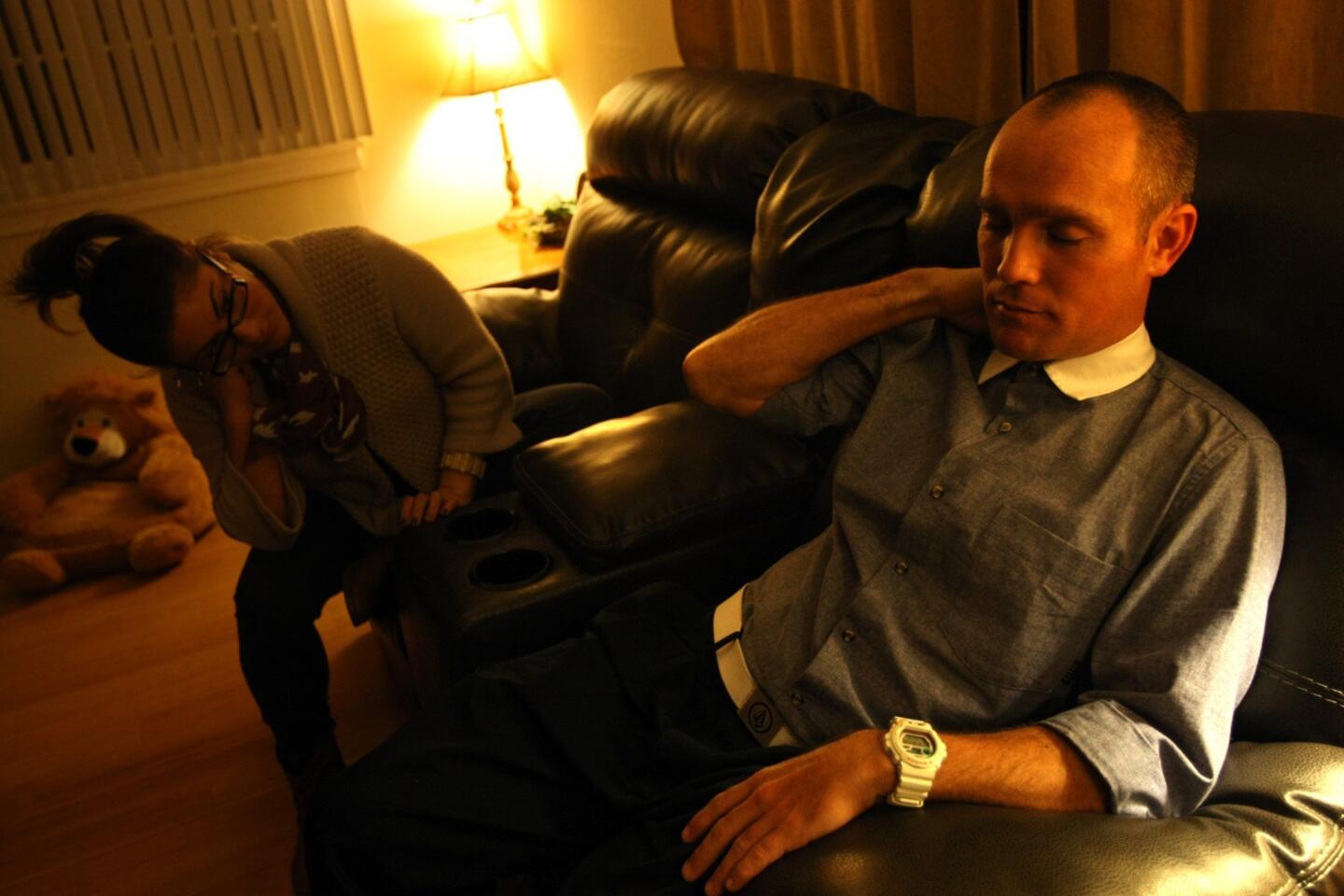

About 1:30 p.m., Evans said she was on her way to watch her teenage son play soccer when her phone rang again. They had discovered the manifesto. “I was told my family and I were not safe.”

After making sure her son was with his father — a retired cop — Evans drove around aimlessly, fearing that Dorner could be waiting for her at her home or police station. Within 20 minutes, she recalled, someone from the LAPD called to make plans for protecting her and her family.

Police say Dorner killed two officers as well as the Irvine couple, and injured three more officers in gun battles, before apparently killing himself last week in the basement of a Big Bear cabin as authorities closed in on him.

Evans has not yet returned to her home. She and police officials said Evans has continued to receive threats. In addition, someone tried to break in to her home, police said.

“I honestly don’t think my life will ever be normal the way it was before. This was such an extraordinary circumstance, I don’t know if I’m ever going to feel safe in my home again,” Evans said. “Years from now, my family could potentially still be at risk.”

joel.rubin@latimes.com

Times staff writers Christopher Goffard, Kurt Streeter and Andrew Blankstein contributed to this report.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.