Class on parenting becomes a journey through loss, grief and hope

Roshawne Mackey walked into the Jordan Downs community center clutching a pink pamphlet from a funeral over the weekend, her face like stone.

Her niece had been 11 — a diabetic who wasn’t given her insulin shots. The dozen or so women in the parenting class listened as Mackey described how the little girl used to make backpacks out of cereal boxes, how she’d adored Hello Kitty. Mackey’s expression remained stoic, but tears slid from her eyes.

Within minutes, most of the other women were crying too. Across from Mackey, Veronica Hale put her head down on the scratched laminate table and wept for her 4-month-old girl, who had recently died in her sleep. Another woman spoke of her two sons, killed years before in separate murders. Jamie Drear thought of her boy — still alive, but locked in a state mental hospital for an assault committed during a schizophrenic episode.

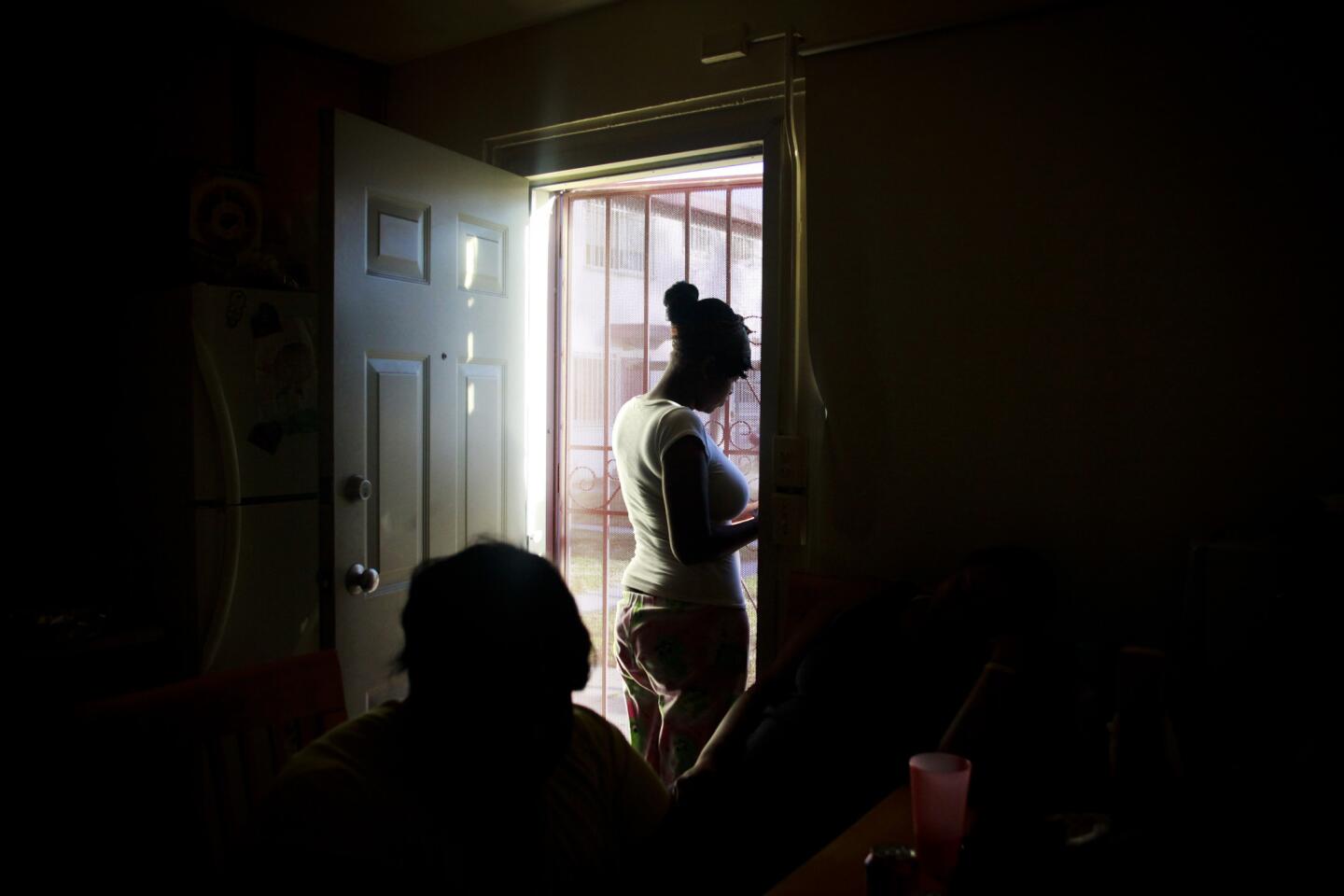

PHOTOS: Sharing loss in Jordan Downs

Their teacher, Sydnia McMillan, silently passed out tissues.

A retired elementary school principal in her late 50s, she’d been hired to give parenting tips to mothers at the rundown housing project because of her expertise in education. With a master’s degree, a comfortable home in Inglewood and a close-knit family of high-achieving children, she inhabited a different world.

How could she hope to help these women? Only four months into the job, she felt overwhelmed by the unplanned pregnancies and meager job skills, the violence, disease and unnecessary death. In her first weeks of work, she met three mothers who had lost more than one son to murder.

Staring at her sobbing students, she had an idea. “Today we’re going to talk about the process of grief and loss,” the teacher said.

I too have lost a child, she said softly. Like you, I know what it’s like to feel sorrow so heavy I can’t imagine rising from bed in the morning.

Often over the next eight months, the women in her class would think back to the lesson she offered that day, as they set about trying to change their lives.

::

McMillan is among about two dozen teachers, social workers and others who descended upon Jordan Downs last March as part of an unprecedented campaign to transform the Watts project from a long-standing hub of violence and poverty into a safe and appealing community that can draw in wealthier residents.

The plan, which will depend heavily on millions of dollars in still-uncertain federal funding, calls for replacing the shabby buildings with condominiums, apartments, fresh lawns and gardens.

McMillan’s job is to help prepare the way.

Her class for English-speaking mothers meets every Monday morning, sometimes with more than 10 women gathered around the table, sometimes with as few as three. Like McMillan, all of her students are African American. Some have lived in Jordan all their lives.

On paper, the curriculum is standard stuff: instruction on the importance of family rituals and early literacy, advice on getting kids to eat their vegetables and heed the rules. In reality, the lessons often veer into edgier territory.

A conversation on conflict resolution, for instance, morphed into a back-and-forth over a 24-year-old woman’s brawl with her boyfriend’s new girlfriend — in front of their kids.

The young woman had come to class with a black eye and a profane new tattoo across her knuckles, boasting of her toughness.

“Have you learned anything in this class that will help you?” McMillan asked.

The woman nodded. “I can walk away.”

She paused a moment.

“But if they keep talking, I turn around and sock ‘em.”

The teacher sighed. “What am I going to do with you?” she asked.

The class broke into laughter.

::

In time, McMillan could see how hungry the women were to do things differently.

They wanted to help their children do better in school than they had done. They diligently practiced Spanish at the end of every class, smiling shyly as they tried to roll their “rrs,” because they thought it would help them get jobs in their increasingly Latino neighborhood.

Among the most determined students was Drear, 42. Six feet tall and soft-spoken, Drear began having children in junior high. Her daughter Krystal Jones, a high school dropout struggling to find direction in life, was 27. Her son Eric, the one committed to a state hospital for assault, was 25.

She wanted them to be able to make it — for Krystal to “be able to focus on herself, and be able to provide for herself,” and for Eric “to be in society and function … and be around the family again, so we can be a family. We missing him so much.”

Adding to her worries, she had become a full-time parent again. A social worker found her three nieces, ages 7 to 17, living as squatters in a house with no heat, hot water or power. They had come to live in the one-bedroom apartment Drear already shared with her daughter.

She has posted their artwork and school papers on her living room wall. Every morning, she tells them the same thing: “You’re going to school, every day.”

Again and again, though, McMillan heard of personal tragedies: “Loss from death. Loss from incarceration. Loss from accidents. Lots of loss.”

Sometimes the pain emerged indirectly.

Hale, a 24-year-old mother of four with an ever-changing hairstyle and an enviable wardrobe, held court in class with gossip and quips. She had dropped out of high school after becoming pregnant and getting into a fight with another student, but she was sharp. Tell her something once — a string of Spanish vocabulary or a list of “positive family attributes” — and she’d remember it forever.

She told charming, meandering stories. McMillan would ask her about financial planning and she’d ramble about a child she found wandering alone at the project and how she met a Latino man during her search for the mother who complimented her on her Spanish. That would somehow lead to a discussion of the nicknames for various landmarks around Jordan Downs and — even after a plea from McMillan to stay on topic — an endorsement of President Obama.

One subject Hale rarely mentioned in class was her 4-month-old daughter, Angeliyah, who died last January in her sleep, apparently of sudden infant death syndrome. A glance at her back told another story: Her daughter’s name had been tattooed in black ink across her skin.

Last New Year’s Eve, she poured her anguish out on Facebook.: “angeliyah I missing u so much.... you not being here with us eating me up .. in tears missing my baby.”

Mackey, the woman whose niece died, was more closed off.

When outreach workers knocked on her door last year, the 46-year-old had taken to staying in her apartment with the shades drawn, day after day.

She had never gotten over the death a decade before of her toddler son, who was killed in a car accident. Her husband died soon after of an aneurysm. She gave up being a foster parent, which once had filled her house with noise and laughter.

McMillan persuaded her to join the class, even though she had no kids at home, hoping to dislodge her from her hide-out. She often sat without speaking, her face drawn and impassive.

When Mackey’s niece died, McMillan went to the funeral with her.

The following Monday, the teacher decided on the spot to tell the women about a death they didn’t know about: that of her own son.

He was a doctor, just 32 years old. In 2005, he went to Jamaica on vacation and died. She keeps the details to herself.

The grief paralyzed her, she told her students. She was working as a principal at an elementary school in Carson and found she could no longer do the job she once loved.

“Every little boy was my little boy, just a constant reminder. I was coming to work very sad, crying before I went into work,” she explained later. “I just didn’t have the energy to lead anymore.”

Eventually, after taking a few years off to help raise her grandchildren, she felt the need to return to work and heard about the job at Jordan Downs.

“There is life beyond the loss,” she told the class.

From that day, the tenor of the class shifted; the women began to open up — even Mackey.

“It helped me realize, it’s OK to talk about it,” she said. “I don’t feel so shelled around me, like I used to.”

Mackey told the others just how despondent she had become. A few years after her son’s death, she decided to kill herself with a kitchen knife. She stood in her living room, the blade pointed toward her heart, when her sister appeared at her door.

“That was nothing but God,” she told the class. She was meant to live.

The day Mackey spoke, McMillan announced that she was starting a grief group on her own time, for parents whose children had died.

The first meeting, in July, had six people. By Christmas, when she held a candle-lit memorial service at the nearby fire station, so many came they ran out of chairs.

McMillan led the ceremony that night, her voice breaking as she spoke of her son. Her involvement at Jordan, she said, “has given my grief a direction. Before, I had nothing to do with the grief but grieve. But now I have a purpose … a way to express it so it is helping others.”

Mackey started attending the meetings. She got more involved in church, spending more time with family and friends. She also enrolled in a program at Jordan to get her GED, part of the initiative to transform Jordan. On the day her certificate was awarded last fall, she stood in front of a small crowd to read a poem she had written.

“Can people look inside and see that I have feelings? Do they know it’s hard to make my way, to keep on trying every day?”

The poem hailed McMillan and her GED teacher — “those who kept me there, every day, what made me the person that I am today.”

::

By late winter Mackey still hadn’t found a full-time job, though she was working part time at a day-care center.

Drear was thrilled to see Krystal finally get her GED. But then she learned her niece, one she had just taken in, was pregnant. She just turned 18.

A few days later, Hale’s cousin, a woman well known to many in the class for her colorful personality, died in her sleep. No one knew why. Not yet 40, she left seven children. Some of the kids had fathers who could take them in, but others might wind up in foster care. The women worried about how to pay for the funeral.

Hale’s face suddenly crumpled. She was reminded of the day she’d gone door to door seeking donations for the burial of her 4-month-old.

She waved her hand, as if to push the memory away. She had to focus. The following day, she was going to take her GED test.

“I’m ready,” she said. “So I can get me a job.”

McMillan smiled in encouragement.

After class, she retreated to her office, saddened by her students’ latest troubles and marveling at their perseverance.

“It’s a steep challenge, every day they wake up,” she said. “But their gift, their spirit, is they don’t stop.... The mere fact that they continue to come to class means they continue to have hope. That’s the one thing that has not died —- hope for a better future.”

This is one in a series of occasional articles on the attempt to remake Jordan Downs.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.