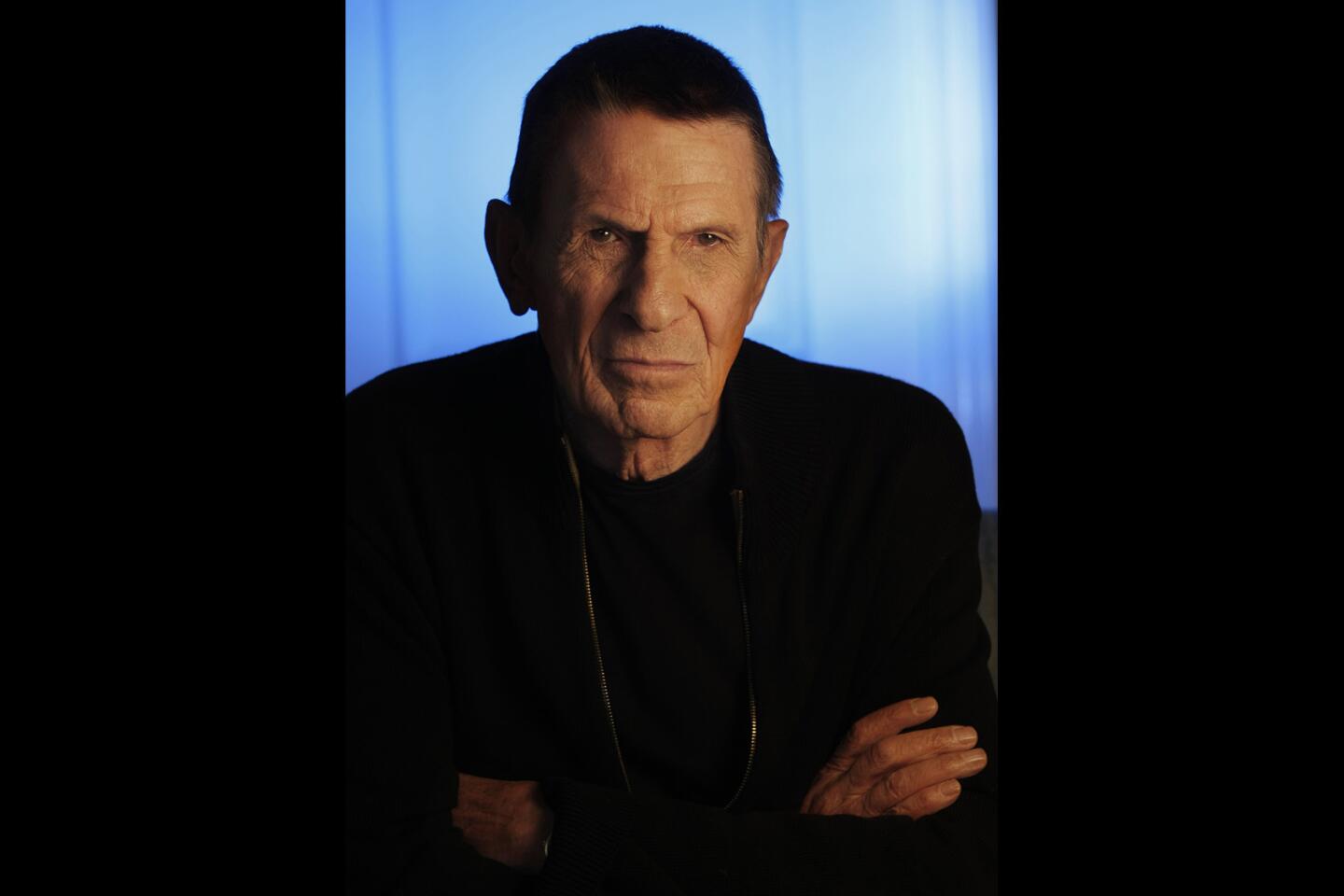

Leonard Nimoy dies at 83; ‘Star Trek’s’ transcendent alien Mr. Spock

When Leonard Nimoy was approached about acting in a new TV series called “Star Trek,” he was, like any good Vulcan contemplating a risky mission in a chaotic universe, dispassionate.

“I really didn’t give it a lot of thought,” he later recalled. “The chance of this becoming anything meaningful was slim.”

By the time “Star Trek” finished its three-year run in 1969, Nimoy was a cultural touchstone -- a living representative of the scientific method, a voice of pure reason in a time of social turmoil, the unflappable and impeccably logical Mr. Spock.

He was, as The Times described him in 2009, “the most iconic alien since Superman” – a quantum leap for a character actor who had appeared in plenty of shows but never worked a single job longer than two weeks.

Nimoy, who became so identified with his TV and film role that he titled his two memoirs -- somewhat illogically -- “I Am Not Spock” (1975) and “I Am Spock” (1995), died Friday at his home in Bel-Air. He was 83.

The cause was end-stage chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, said his son, Adam.

Nimoy revealed last year that he had the disease, a condition he attributed to the smoking he gave up 30 years earlier.

While he was best known for his portrayal of the green-tinted Spock, Nimoy more recently made his mark with art photography, focusing on plus-sized nude women in a volume called “The Full Body Project” and on nude women juxtaposed with Old Testament tales and quotes from Jewish thinkers in “Shekhina.”

He also directed films, wrote poetry and acted on the stage.

As Spock, he was the pointy-eared, half-Vulcan, 23rd century science officer whose vaulted eyebrows seemed to express perpetual surprise at the utterly illogical ways of the humans who served with him on the starship Enterprise.

Spock could barely wrap his mind around feelings. He was the son of a human mother and a father from Vulcan – a planet whose inhabitants had chosen pure reason as the only way they could survive. When he thwarted deep-space evil-doers, it was with logic simple enough for a Vulcan but dizzying for everyone else, including his commanding officer, Capt. James T. Kirk, played by William Shatner.

While worlds apart from the racial strife and war protests of the 1960s, “Star Trek” explored such issues by setting up parallel situations in space, “the final frontier.”

“Spock was a character whose time had come,” Nimoy later wrote. “He represented a practical, reasoning voice in a period of dissension and chaos.”

He also turned Nimoy into an unlikely sex symbol.

When he spoke at Ohio’s Bowling Green State University in the 1970s, a young woman asked: “Are you aware that you are the source of erotic dream material for thousands and thousands of ladies around the world?”

“May all your dreams come true,” he responded.

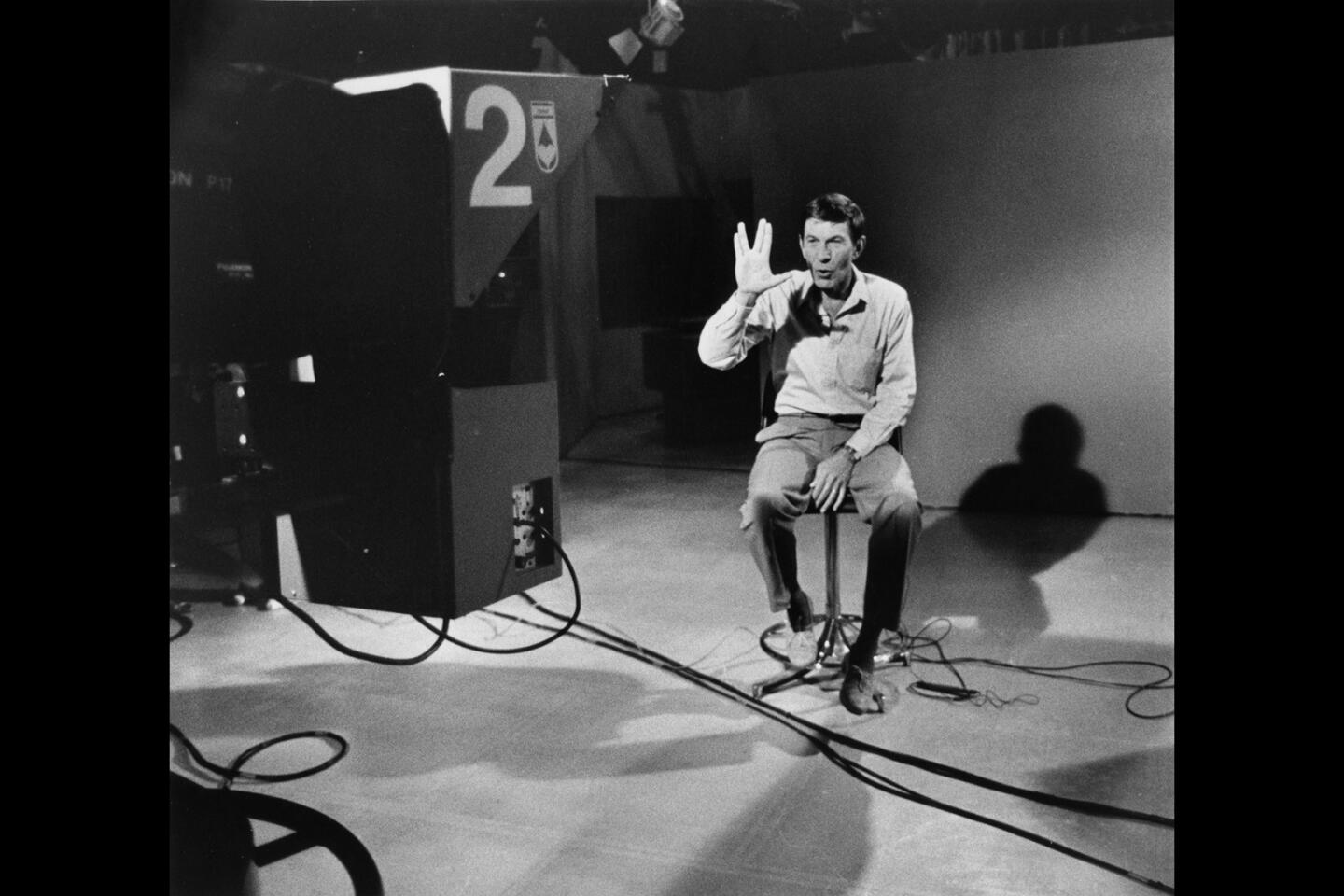

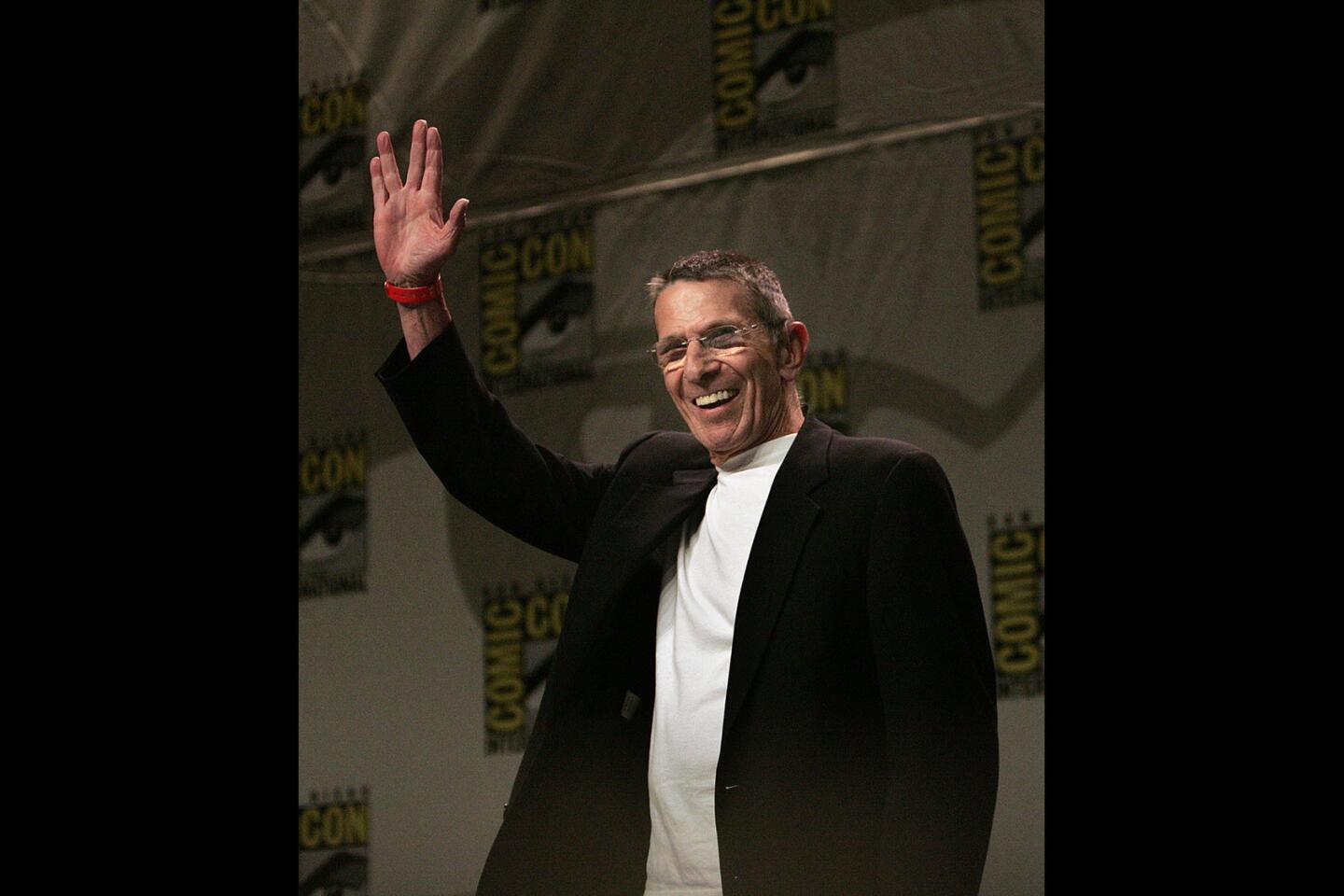

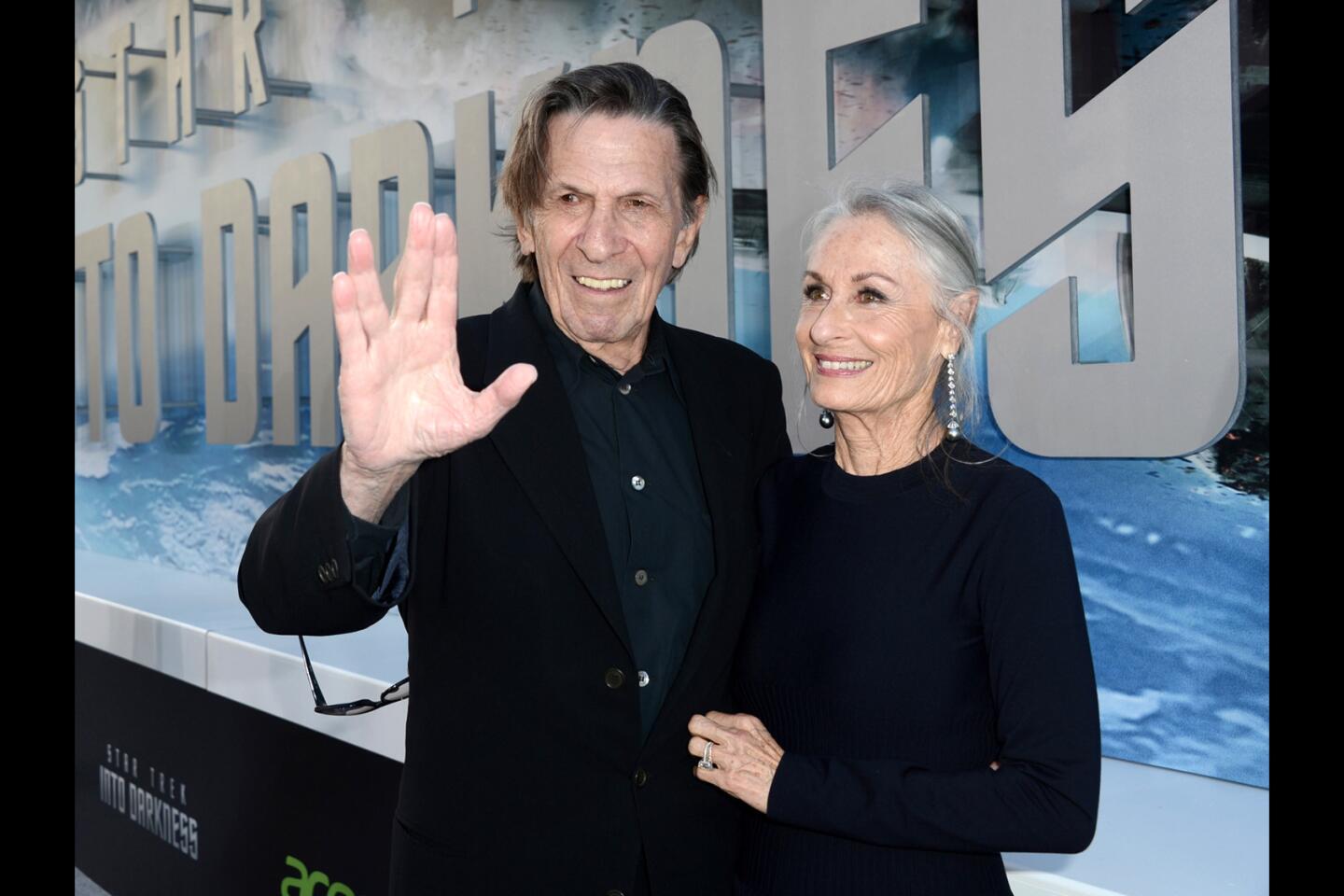

Trekkies everywhere greeted each other with Nimoy’s “Vulcan salute” – a gesture he adapted from one he had seen at an Orthodox synagogue when he was a boy.

“I was awestruck,” Nimoy recalled in a 2004 Times interview.

At the altar, five or six men chanted prayers with their arms raised. They held their hands with fingers parted between the ring and middle fingers and thumbs stuck out – a representation, Nimoy said, of the Hebrew letter shin, the start of Shaddai, a term for God.

LSD guru Timothy Leary once flashed Nimoy the Vulcan salute. So did cabdrivers who sped by on the street, and interviewers who momentarily suspended their journalistic detachment. At a 2007 fundraiser in Los Angeles, presidential candidate Barack Obama spied Nimoy across a room, smiled, and held up his hand in the familiar gesture.

Four years later, President Obama told ABC’s Barbara Walters that his critics wrongly believed he was “Spock-like,” or too analytical.

For much of his career, Nimoy had to deal with the same sort of perception problem.

While his 1975 autobiography was “I Am Not Spock,” he later called the title a mistake because it was so easily misconstrued. In the book, he said he couldn’t think of a TV character he would sooner have played.

At the same time, he was disquieted by mountains of fan mail addressed not to Leonard Nimoy, but to “Mr. Spock, Hollywood, Calif.”

The melding of actor and character was sometimes uncomfortable. On a tour of Caltech, Nimoy was asked his thoughts about complex projects by students who must have believed he had a Spock-like insight.

“I would nod very quietly, and very sagely I would say, ‘You’re on the right track,’ ” he told the New York Times in 2009.

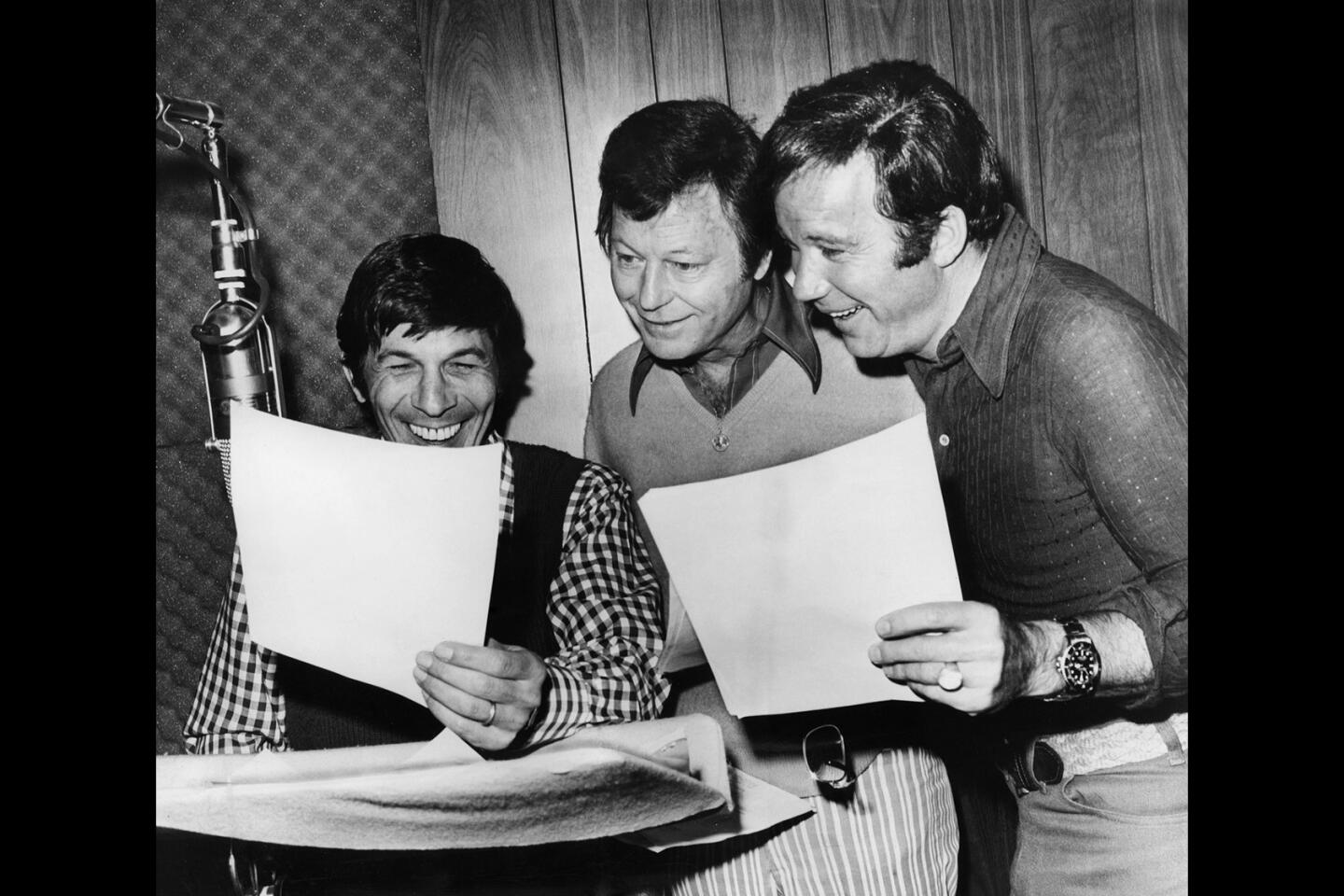

Nimoy appeared in the original “Star Trek” TV series, which ran on NBC from 1966 to 1969. He received three successive Emmy nominations.

He also was Spock in feature films, including: “Star Trek: The Motion Picture” (1979); “Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan” (1982); “Star Trek III: The Search for Spock” (1984); “Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home” (1986): “Star Trek V: The Final Frontier” (1989); and “Star Trek VI: The Undiscovered Country” (1991).

He retired from “Star Trek” pictures until 2009, when he became Spock Prime, a Mr. Spock who inhabited an alternate universe in J.J. Abrams’ “Star Trek.” He did a cameo performance as the same character in “Star Trek Into Darkness” (2013).

Rumors of Spock’s impending on-screen demise in “Star Trek II” prompted death threats to director Nicholas Meyer.

“I received a helpful letter that ran: ‘If Spock dies, you die,’ ” Meyer wrote in “The View from the Bridge: Memories of Star Trek and a Life in Hollywood.”

The scene was filmed anyway -- so affectingly, according to Meyer, that the crew wept openly “as the dying Spock held up his splayed hand and enjoined Kirk to ‘live long and prosper.’ ”

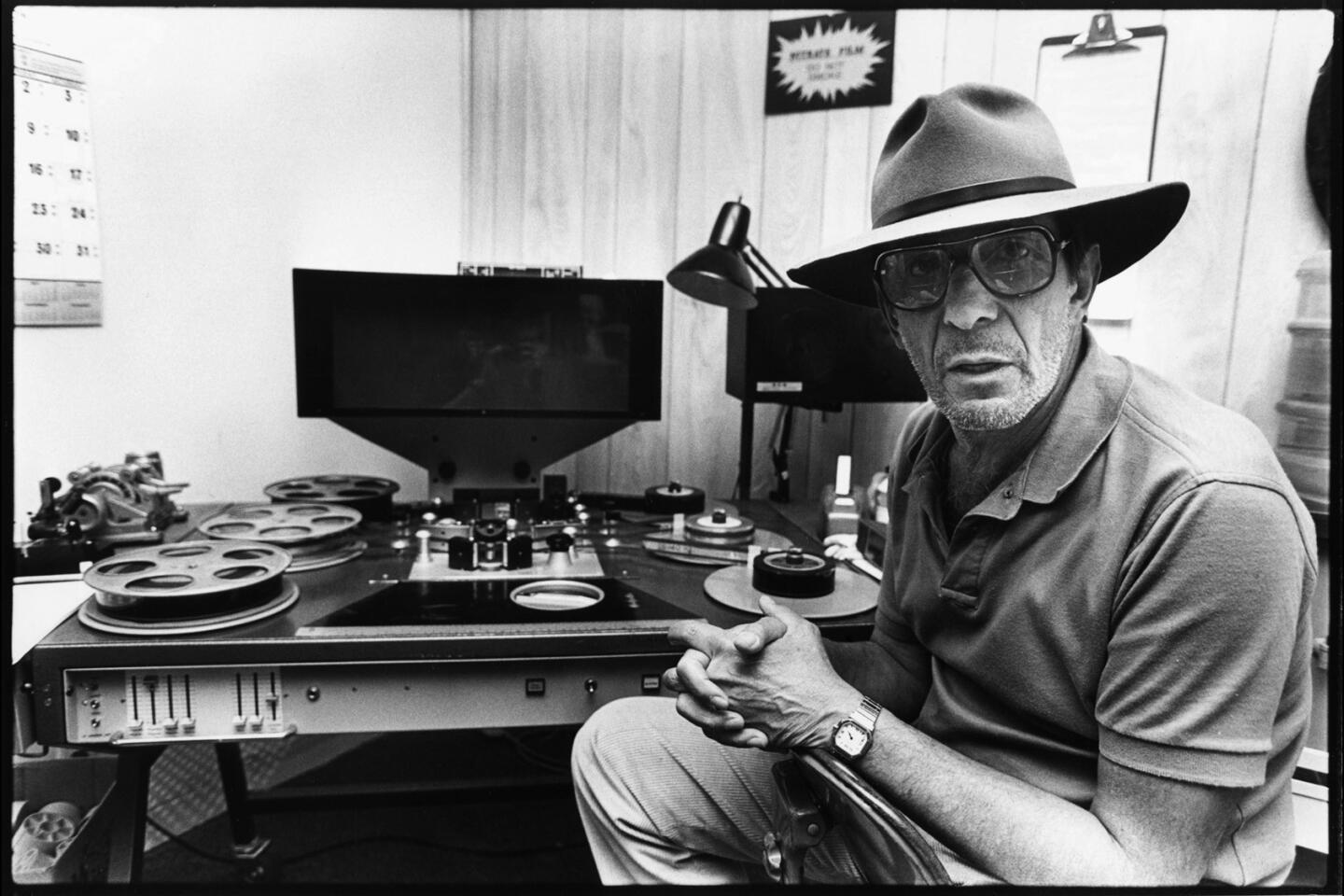

Thanks to an ancient Vulcan ceremony and some tortuous plot twists, Spock was resurrected in “Star Trek III.” Nimoy directed that film, as well as “Star Trek IV.” He went on to direct the 1987 comedy “Three Men and a Baby” and the 1988 drama “The Good Mother.”

In numerous public appearances, he pointed out the irony of his success.

“My folks came to the U.S. as immigrants,” he said in a 2012 speech at Boston University. “They were aliens, and then became citizens. I was born in Boston a citizen, and then I went to Hollywood and became an alien.”

Born on March 26, 1931, Leonard Simon Nimoy first acted in a community settlement house for immigrants. At 17, he was cast in a Boston production of the Clifford Odets play “Awake and Sing!”

To his parents’ chagrin, it confirmed his passion for acting. The play was about a Jewish family much like Nimoy’s and it probed his kind of teenage confusion.

“I was electrified,” he recalled. “The author gave me a voice when I was struggling to find my own.”

Nimoy’s Ukrainian-born father Max, who ran a barber shop in a Boston tenement neighborhood, tried to warn his son about the dangers ahead.

“Learn to play the accordion,” he urged. “You can always make a living with an accordion.”

Instead, Nimoy briefly studied drama at Boston College, sold vacuum cleaners, and, at 18, left for acting school in California. He dropped out after six months.

His earliest film roles include Narab, a Martian in the 1952 film “Zombies of the Stratosphere.” The same year, he scored his first title role, in the boxing movie “Kid Monk Baroni.”

After a stint in the Army, Nimoy he was back in Los Angeles by the mid-1950s, studying acting and picking up work on shows like “Dragnet,” “Bonanza,” “Dr. Kildare” and “The Man from U.N.C.L.E.”

In 1965, he drew the attention of Gene Roddenberry, the producer behind the upcoming “Star Trek” series.

In an early scene, Spock and company were huddled over a computer screen and he uttered the one-word line: “Fascinating.”

Then he tried it again.

“The director gave me a brilliant note which said: Be different,” Nimoy recalled in an interview for the Archive of American Television. “Be the scientist. Be detached. See it as something that’s a curiosity rather than a threat.”

“I said, ‘Fascinating.’ Well, a big chunk of the character was born right there.”

Despite its fans’ enthusiasm, the show ended its run in 1969, a victim of low ratings and tepid support from NBC.

By then, Nimoy was famous. Even his much-derided 1967 record album, “Leonard Nimoy Presents Mr. Spock’s Music from Outer Space” sold more than 130,000 copies.

He put in an unsatisfying two years on “Mission: Impossible” and then pursued a range of interests befitting the Renaissance man he had become.

He received a master’s degree in education from Antioch University. He turned out seven books of poetry and created a comic book series with science fiction writer Isaac Asimov. He directed six films and, from 1978 to 1980, toured in a one-man show, “Vincent,” about Vincent Van Gogh.

From 1977 to 1982, he hosted the documentary TV series “In Search Of …” about paranormal phenomena. In 1978, he played a pompous self-help guru in the film “Invasion of the Body Snatchers.”

He poured himself into projects reflecting his Jewish heritage. In 1982, he appeared as Israeli Prime Minister Golda Meir’s former husband in the TV movie “A Woman Called Golda”; nine years later, he played a Holocaust survivor who waged a courtroom battle against Holocaust deniers in the TV movie “Never Forget.”

His photography book, “Shekhina,” pictured nude and sensually draped women, with a cover shot of a woman wearing tefillin, Jewish ritual objects traditionally worn by men. It raised some hackles in the Jewish community, but Nimoy said it was his vision of feminine Jewish spirituality.

“I’m not introducing sexuality into Judaism,” he said. “It’s been there for centuries.”

In 2009, the Santa Monica Museum of Art exhibited images Nimoy made in Northampton, Mass., of strangers willing to be photographed as their “secret selves.”

The show, called “Who Do You Think You Are?” featured a rabbi with a leather vest over his bare torso and a conservatively dressed female psychologist toting a chain saw.

Asked by a Times reporter about his own secrets, Nimoy demurred.

“I have to laugh,” he said. “I have no secrets left. I revealed it all a long time ago.”

Nimoy was married to Sandi Zober from 1954 to 1987, when they divorced.

In addition to his children from that marriage, son Adam and daughter Julie, his survivors include Susan Bay, his wife since 1989; his stepson Aaron Bay Schuck; six grandchildren; a great-grandson; and his brother Melvin.

Instead of flowers, Nimoy’s family asks that donations be made in his memory to the Everychild Foundation, P.O. Box 1808, Pacific Palisades, CA 90272; the COPD Foundation, 20 F Street NW, Suite 200-A, Washington, D.C. 20001; Beit T’Shuvah treatment center, 8831 Venice Blvd., Los Angeles, CA 90034 or the Bay-Nimoy Early Childhood Center at Temple Israel of Hollywood, 7300 Hollywood Blvd., Los Angeles, CA 90046.

ALSO:

Leonard Nimoy: ‘Star Trek’ fans can be scary

Leonard Nimoy in search of human life forms through photography

When Spock met Hendrix: ‘Trek’ icon Leonard Nimoy’s cosmic moment

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.