New York state trooper who investigated the disappearance of Robert Durst’s wife testifies in L.A. murder case

Robert Durst’s wife, Kathleen, who disappeared decades ago, told her divorce attorney shortly before she vanished that the eccentric millionaire “threatened to kill her,” a retired New York state trooper who investigated her missing person case test

Robert Durst’s wife, Kathleen, told her divorce attorney shortly before she vanished decades ago that the eccentric millionaire “threatened to kill her,” a retired New York state trooper who investigated her missing person case testified Monday.

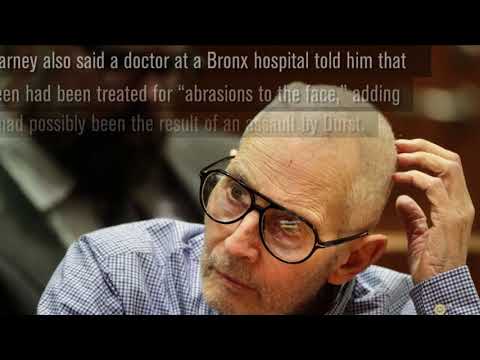

The trooper, James Harney, is one of several witnesses called to the stand by prosecutors in Los Angeles to testify against the real estate tycoon, who lived for years under the suspicion of New York authorities and now stands accused of shooting his best friend to silence her for what she knew about Kathleen’s 1982 disappearance.

Prosecutors allege Durst, 74, shot his friend, crime writer Susan Berman, in the back of the head inside her Benedict Canyon home in late December 2000. He has pleaded not guilty.

Harney testified that he was assigned to look into Kathleen’s disappearance on Feb. 5, 1982, after police received a call from a concerned friend of Kathleen’s. During Monday’s hearing, Harney read aloud from a three-page missing person report he wrote at the end of his shift.

Kathleen’s attorney told the trooper that during a phone call about a week earlier, Kathleen had expressed fear for her safety and said that Durst had “threatened to kill her,” Harney said, reading from his report.

The trooper also said that he spoke to a doctor at a Bronx hospital, who told him that about two weeks earlier Kathleen had been treated for “abrasions to the face,” adding that it had possibly been the result of an assault by Durst. No police report had been filed at the time, Harney noted.

Harney’s report mentioned that Kathleen’s brother said during an interview that his sister and Durst had a “deteriorating” relationship.

About 10 p.m. the day he was assigned the case, Harney received a call from Durst reporting Kathleen missing and inviting the trooper over.

During the interview at Durst’s home in South Salem — a hamlet in Westchester County, New York, where the couple sometimes spent weekends — the trooper said Durst told him he’d dropped his wife off at a nearby train station five days earlier to catch a ride back to Manhattan, according to the report. Durst told the trooper that he’d watched Kathleen board the train and saw it leave the station. He told Harney that was the last time he saw his wife but said that he’d spoken to her by phone for about a minute after she returned to their apartment in New York City.

A prosecutor Monday asked Harney if he recalled Durst’s demeanor during the interview that night.

“Unagitated when we started,” Harney said, adding that Durst became “agitated” when asked about Kathleen’s treatment at the hospital for the injuries to her face.

“My impression was he was concerned that we knew about this incident,” Harney said.

But under cross-examination by one of Durst’s attorneys, Harney conceded that Durst had answered all of his questions during the interview. Harney, now 65, testified that he hadn’t noticed anything out of the ordinary at the home that night.

Harney’s testimony was videotaped in case he’s unable to testify at Durst’s trial, which is unlikely to begin until at least 2018.

Prosecutors also gathered testimony from journalist and author Stephen Silverman, who briefly lived in the same New York apartment complex as Berman in the late 1970s. The two became very close, Silverman said, adding that Berman had a habit of describing her ailments in graphic detail.

Silverman, 65, testified that years after Kathleen’s disappearance he learned of a phone call from a woman identifying herself as Kathleen to a dean of the Albert Einstein College of Medicine — where she’d been enrolled — saying she’d be absent that day because she was feeling sick. Silverman said that “a bell went off” in his mind when he learned that the caller had included “graphic details” of the illness.

“This sounds exactly like Susan,” he recalled thinking.

In April, Berman’s friend Lynda Obst testified that Berman once told her she’d called the dean pretending to be Kathleen.

Prosecutors this week also plan to call a doctor who lived near Berman’s Benedict Canyon home and the former assistant chief of the Beverly Hills Police Department.

During a hearing in July, prosecutors displayed a copy of an envelope addressed to “Beverley Hills Police.” Inside the envelope, prosecutors said, was an anonymous note sent to authorities around the time of Berman’s death alerting them to a “cadaver” inside her home. A longtime friend of Durst said it looked like his handwriting.

The millionaire was arrested on suspicion of Berman’s killing at a New Orleans hotel in March 2015 — a day before the airing of the last episode of “The Jinx,” a six-part documentary about Durst’s life. In the episode, Durst mumbles into a hot microphone: “What the hell did I do? Killed them all, of course,” which some have interpreted as a confession to multiple homicides.

The documentary highlights Kathleen’s disappearance, Berman’s killing and the 2001 fatal shooting of Morris Black. Black was Durst’s neighbor when he lived in Galveston, Texas, under an assumed name and posing as a mute woman. Durst said the gun went off accidentally while defending himself against Black, but he admitted to dismembering the man’s body. He pleaded not guilty to Black’s killing and was ultimately acquitted.

For more news from the Los Angeles County courts, follow me on Twitter: @marisagerber

UPDATES:

6:00 p.m.: This article was undated with additional testimony from the hearing.

3:20 p.m.: This article has been updated with testimony from the hearing.

This article was originally published at 5 a.m.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.