As a teen, he savagely beat a classmate. The attack was forgotten, until he went into politics

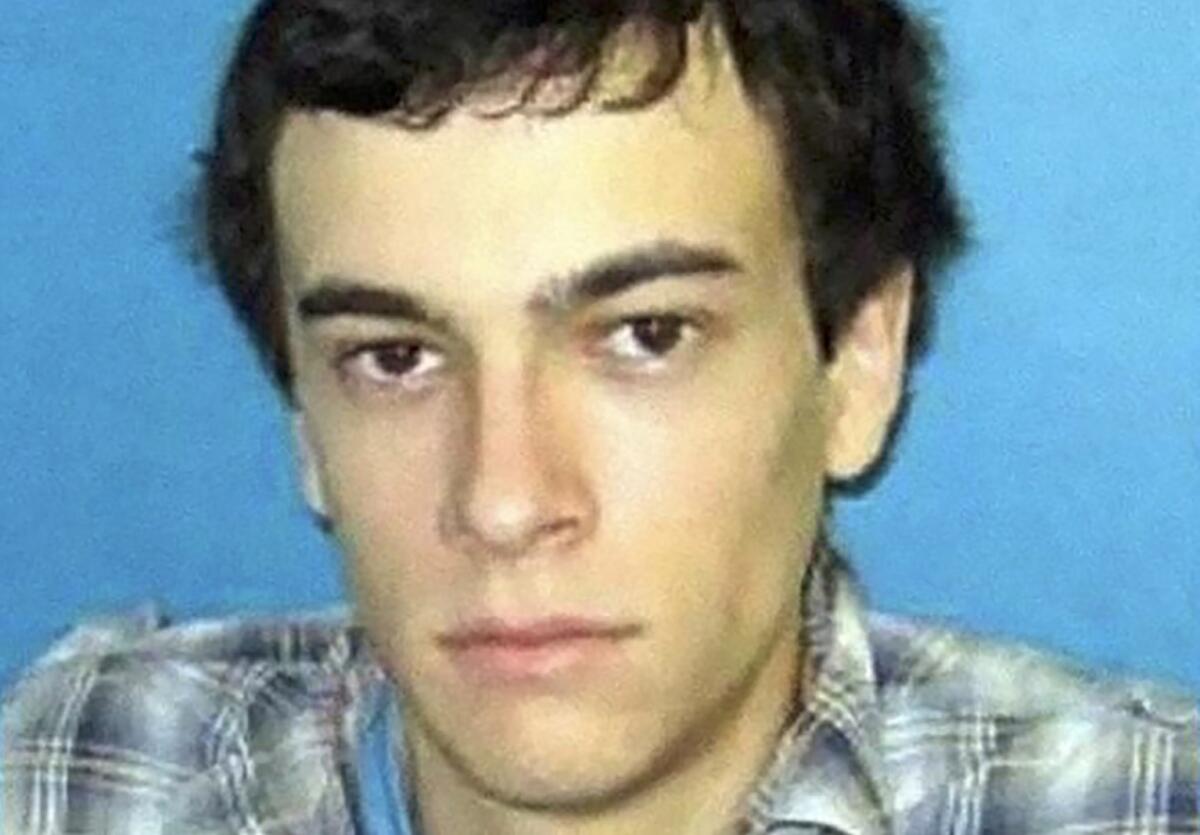

The Republicans of Broward County, Fla., knew little about Rupert Tarsey when he ran for an open slot on the local party’s executive committee. But the young man had some decent political cred.

Before the 2016 presidential election, he told them, he knocked on thousands of doors and got 50 Republicans in the liberal enclave to register to vote to support Donald Trump’s presidential campaign. He worshiped at the same church as the committee’s vice chair and headed a local chapter of the Catholic fraternal group Knights of Columbus. He came from a wealthy California family and followed four generations into a real estate career.

Within months of joining the local party, the 28-year-old was elected secretary in May, defeating two challengers who’d been around longer.

But something felt off about Tarsey for Bob Sutton, chairman of the committee. After a few months, Tarsey went after Sutton’s position, members said, by working to persuade the committee to unseat him. That’s when Sutton started getting phone calls warning him that Tarsey was not quite who he seemed.

“Houston, we’ve got a problem,” he said one caller told him.

It wasn’t long before the story of Tarsey’s past unfolded.

It began a decade ago, some 2,700 miles away at the exclusive Harvard-Westlake High School, a private college preparatory academy where tuition this year is $37,100 and which is a magnet for the children of Los Angeles’ elite.

Rupert Ditsworth, a 17-year-old from Beverly Hills, was a senior. One day in May, he finished an Advanced Placement exam and was waiting for a friend when he saw another schoolmate, Elizabeth Barcay. He invited her to lunch in his Jaguar.

They’d known each other for two years and eaten together before. She accepted.

They took the Jaguar to a Jamba Juice and sipped smoothies. After lunch, Ditsworth asked Barcay if she would go with him to mail something on the way back to school. She agreed.

Soon after, according to court records, he drove past a mailbox and detoured to a quiet residential street, parking at a dead-end with the passenger door up against a wall. There, he told Barcay he had thoughts of suicide. She suggested he drive back to school and see a counselor.

Instead, according to court records, he reached inside his backpack, pulled out a claw hammer and started swinging. Ditsworth delivered dozens of crushing blows, smashing Barcay’s nose and leg, splitting her scalp and giving her two black eyes, the records say. Her family said they counted at least 40 visible wounds.

During a struggle, the weapon broke. So Ditsworth grabbed Barcay’s throat and tried to strangle her, she testified during a preliminary hearing.

Barcay said she bit down on his finger to stop the attack. He let go.

“I’m done,” he screamed.

Bloody and wounded, Barcay managed to escape from the car before collapsing in front of a nearby home.

She survived the attack, emerging with fierce resolve. Five days later, she went to prom — in a wheelchair — and was crowned queen, the high school’s student newspaper reported at the time. Barcay could not be reached for comment for this article.

Prosecutors filed three felony charges against her attacker: one count of attempted murder and two counts of assault with a deadly weapon. If convicted of those charges, Ditsworth was facing the rest of his life behind bars.

But he never spent a day in jail.

What followed instead was a series of moves that gave the teenager a near-clean criminal slate, allowing him to reinvent himself in Florida.

“When you have a lot of money, you can kind of get away with stuff,” said Celeste Ellich, vice chair of the Broward County Republican Party, who had supported Tarsey’s secretary bid before she knew about his past. “They thought they had it buried.”

Deputy Dist. Atty. Ed Nison, who prosecuted the case in California, told The Times that because Ditsworth was relatively young, had no prior record and suffered from psychiatric issues, putting him in jail “would not serve the purpose that it’s supposed to serve.”

“The goal was to avoid a reoccurrence of this kind of behavior,” Nison said. “And simply locking him up wouldn’t have done anything to prevent future behavior under these circumstances.”

But at the time, others saw the situation differently.

“You should have gone to prison,” David Barcay, the victim’s father, told Ditsworth at a dramatic court hearing in 2010. “Instead, you’re going to school and making friends and enjoying the outdoors and posing for pictures with your fraternity brothers with paintball guns in army fatigues …. You have moved to Florida and created a life that has allowed you to forget.”

You should have gone to prison.

— David Barcay

After the attack, Ditsworth’s parents immediately admitted him to a hospital for mental health treatment. Ditsworth, who previously had been diagnosed with autism, spent three months in a psychiatric hospital in Texas, then four years in a residential treatment program for autistic students in Florida, according to court records.

A band of private attorneys represented him in criminal proceedings, brokering a plea deal with prosecutors that involved pleading no contest to one count of assault with a deadly weapon in exchange for six years of probation. A judge terminated the terms after five.

His attorneys argued, according to court records, that Barcay screamed when Ditsworth expressed suicidal thoughts, and his hypersensitivity to sound caused him to react to “silence the noise.”

Court records show his family settled a civil lawsuit brought by his classmate for $1.17 million.

Ditsworth changed his name to Rupert Tarsey, after his mother, Patrice Tarsey, an attorney who represented her son and testified for him in the name-change proceedings, according to court records. A judge granted the request in October 2010.

Two years earlier, he had filed a separate request to change his name to Robert Ditsworth, to carry on the name of his late grandfather, court records show. It was dropped when he didn’t show up to a hearing in 2009. Before that name change request, and while his criminal case was pending, someone using the name “Rypert Ditworth” and Tarsey’s birthday registered to vote in Broward County, a Florida Department of State spokeswoman confirmed.

In Florida, Ditsworth continued to get 12 hours a week of one-on-one behavioral therapy. About a year after the attack, he made the dean’s list at Nova Southeastern University in Fort Lauderdale.

He graduated with multiple honors and in 2013 earned a master’s in business administration. Property records show he now owns a $1.7-million waterfront condo with a pool, basketball court and home theater.

Over the course of more than two years, a psychotherapist sent at least 21 letters, which were obtained by The Times, to the Los Angeles County Probation Department describing Ditsworth’s progress.

In a letter from December 2011, she wrote that Ditsworth’s close friends from college named him godfather of their first child. In another letter a year later, she wrote that Ditsworth lovingly cared for his new cockatiel and delighted in giving his pet new toys.

Heidi Rummel, a professor at USC Gould School of Law, said that, while Ditsworth’s outcome was very unusual, he did well with a second chance.

“That second chance is not afforded to most — kids of color, kids of poor communities. When they commit a crime like that, in most cases, they spend many, many years in prison,” Rummel said. “A lot of kids do well with a second chance. We should be thinking about that more broadly for the kids who never had a first chance.”

Almost a decade after the attack, his attorneys cited much of the same progress detailed in the letters when they asked a judge to reduce his felony conviction to a misdemeanor.

“Rupert was an immature 17-year-old autistic high school student with multiple untreated documented neurological and communication disorders,” they wrote in the application, filed last year. “A felony conviction would constitute an almost insurmountable impediment to being granted a license, much less obtaining employment in the field in which he is trained.”

It worked. A judge granted the request on Jan. 12, 2016.

Two days later, with the felony scrubbed from his record, Rupert Tarsey registered to vote.

The Broward County Republican Party was already beset by fundraising problems and leadership turnover. Tarsey had been putting out feelers to committee members, asking if they’d support him in a bid for chairman.

“The minute he became secretary, he decided he wanted to be chair,” said Ellich, the committee’s vice chair. “He told me he wants to be ‘president of Earth.’ I thought he was kidding. I didn’t take any of that serious at the time, but I think he truly believes that.”

He told me he wants to be ‘president of Earth.’

— Celeste Ellich, vice chair of the Broward County Republican Party

When his past came to light, the group fell into disarray. Some felt they’d been deceived. Others were shocked that Tarsey had so eagerly jumped into the spotlight with such a disturbing history of violence. Many wanted him out.

“I am all for rehabilitation and second chances, but this individual went through extensive means to hide his name,” said Sutton, the group’s chair. “No self-respecting Republican, Democrat or independent would support an individual who took a claw hammer to a female.”

In an email to committee members soon after the revelations reached the board, Tarsey said the negative attention was retaliation for supporting efforts to unseat Sutton. The incident a decade earlier, he wrote, resulted from a verbal argument with a classmate that turned physical when his classmate kicked him and pinned him against the side of the car. He used the hammer, he said, in self-defense.

“BUT TO BE CLEAR,” he wrote, “EVEN THOUGH I WAS ACTING IN SELF DEFENSE I STILL REGRET WHAT HAPPENED AND FEEL THAT MY ACTIONS WERE UNCALLED FOR.”

That was nearly three months ago.

Despite calls for him to resign, Tarsey hasn’t stepped down. When reached by phone, he declined to comment, other than to say, “I don’t really see how it’s a controversy — this is not a state-level position. This isn’t a public office.”

Two grievances, one filed by Tarsey against Sutton and another by Sutton’s attorney against Tarsey, are pending before the Florida Republican Party.

Until there’s a ruling, the executive committee does not intend to meet. Meanwhile, its website lists the secretary position as vacant.

To read the article in Spanish, click here

alene.tchekmedyian@latimes.com

Twitter: @AleneTchek

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.