His convictions were overturned; he’s in failing health. Will Bobby Joe Maxwell gain freedom in ‘70s serial killer case?

Shortly before Christmas, Bobby Joe Maxwell suffered a massive heart attack, leaving him unable to move or speak.

By all accounts, he is unlikely to recover. Yet Maxwell’s name is on a court docket in Los Angeles, where he is awaiting retrial in a slew of murders attributed to a serial killer who haunted the city’s homeless community in the late 1970s — the “Skid Row Stabber.”

Despite Maxwell’s fading health and a jail informant scandal that led to the reversal of his decades-old convictions, the Los Angeles County district attorney’s office has yet to drop the charges against him. His relatives, attorneys and legal experts fear Maxwell, 68, may die in police custody on suspicion of crimes that prosecutors can’t prove he committed.

“They stole his life,” said Maxwell’s younger sister, Rosie Harmon.

His advocates now pin their hopes on persuading a judge this week to release Maxwell from a hospital, where he’s under 24-hour guard, on compassionate grounds.

Attorneys Fred Alschuler and Pierpont Laidley, who have represented Maxwell for the nearly 40 years he has remained jailed, have appealed to prosecutors since their client fell ill.

Officials would not say if they will oppose the court petition.

“While we are aware of Mr. Maxwell’s medical condition, there are other important factors that we must consider including notification of victims’ families and how the defendant will continue to receive proper medical treatment if he is released from custody, given that he requires specialized 24-hour care,” Deputy Dist. Atty. Bobby Grace said in an e-mail to The Times.

The deaths of at least 10 homeless men in downtown’s skid row were laid at the hands of the same killer. Maxwell was convicted in two of the cases during a 1984 trial. Both convictions were overturned in 2010 after it was revealed that a notoriously unreliable jailhouse informant had lied on the stand. Maxwell has remained in legal limbo for eight years, while prosecutors decided whether to retry the case and a series of motions and discovery issues delayed proceedings.

The oldest of six siblings from Columbia, Tenn., Maxwell moved to California in 1977 with dreams of becoming a karate instructor, said Harmon, 65.

“He was just a good, kind-hearted person,” she said. “He didn’t mean no harm to nobody.”

But within two years of moving to Los Angeles, Maxwell was branded a serial killer.

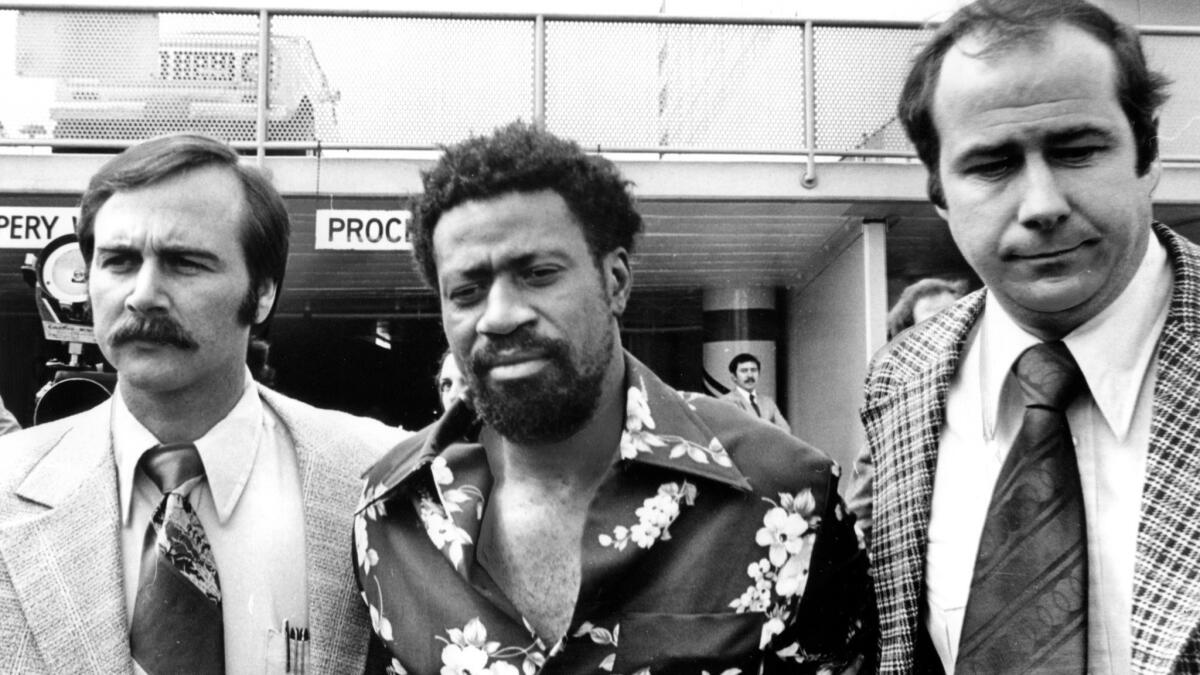

Police believe the “Stabber” victims were killed over several weeks in October and November 1978. Maxwell was arrested in April 1979.

Almost all of the victims were described as homeless and found dead of stab wounds to their upper bodies in alleyways, parking lots and behind bars between 3rd and 7th streets.

The victims were Jesse Martinez, 50, Jose Cortez, 32, Bruce Emmet Drake, 46, J.P. Henderson, 65, David Martin Jones, 39, Francisco Perez Rodriguez, 57, Frank Floyd Reed, 36, Augustine Luna, 49, Jimmie White Buffalo, 34, and Frank Garcia, 45.

The killings came at a time when the city was reeling from the panic induced by other infamous serial predators. The “Hillside Stranglers” preyed on sex workers in Los Angeles in 1977 and 1978, and Vaughn Orrin Greenwood, known as the “Skid Row Slasher,” was convicted of killing eight homeless people just years before the “Stabber” attacks began.

Los Angeles police detectives had arrested and then released two other suspects in the killings, but turned their attention to Maxwell after his palm print was found on a park bench near one of the crime scenes, according to Capt. Billy Hayes, who leads the LAPD’s elite Robbery-Homicide Division.

Maxwell had also been previously arrested along skid row for possessing a knife, Hayes said, and some witnesses said they saw a man who looked similar to Maxwell walking away from the scene of a few of the stabbings.

Investigators cast Maxwell as a Satanist who killed to deliver souls to the devil. A notebook containing references to Satan was found at the home of one of Maxwell’s relatives, and drawings in the book were similar to “Satanic symbology” found at some of the crime scenes, Hayes said.

Harmon dismissed the idea that her brother dabbled in Satanism. Maxwell was “raised in the church” and tried to start a bible study program while incarcerated, she said.

In overturning his conviction years later, an appellate court would describe most of the evidence against Maxwell as “circumstantial.” The knife found on Maxwell was consistent with wounds suffered by some of the victims, but investigators could never conclusively link the weapon to the slayings, court records show. None of the witnesses who described the suspect leaving crime scenes could identify Maxwell at trial.

Alschuler and Laidley have long contended the Los Angeles Police Department captured the wrong person.

Before Maxwell, another suspect known to frequent areas where some victims were found had been under surveillance. But detectives never found physical evidence linking him to the case and he was released, records show.

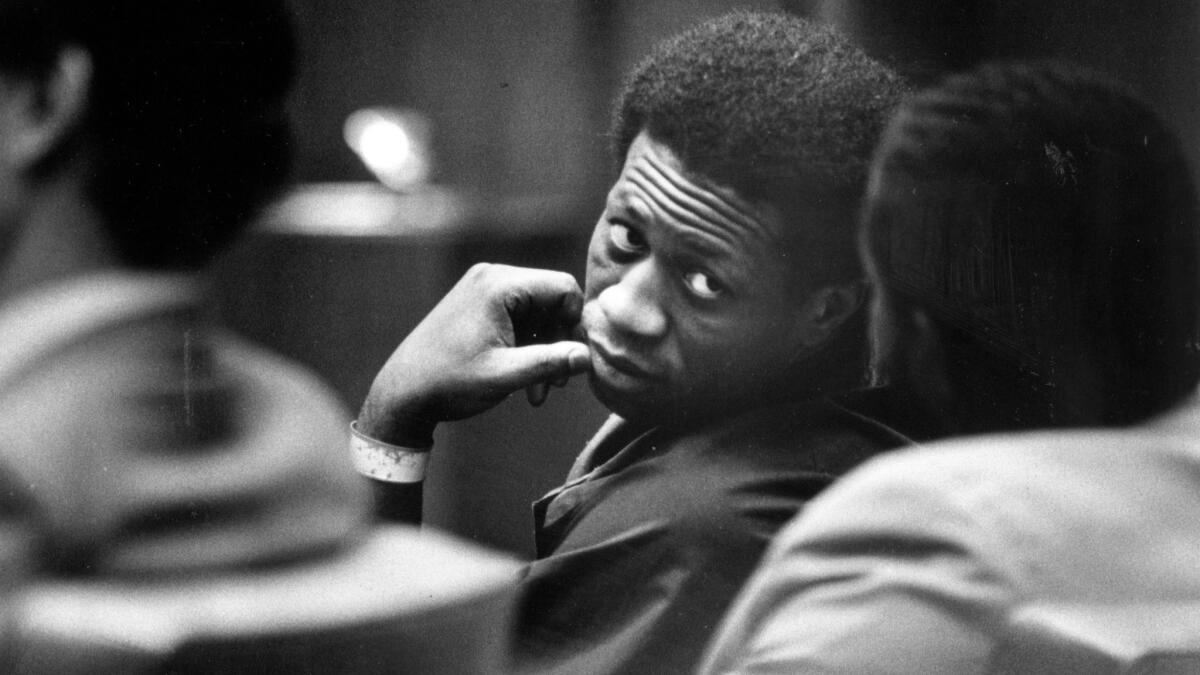

The prosecution’s star witness at Maxwell’s trial was jailhouse informant Sidney Storch, who claimed Maxwell confessed to the killings. Maxwell was convicted of two of the 10 murders and sentenced to life in prison. The same jury acquitted him in three of the slayings and deadlocked on the remaining five.

Doubts about Maxwell’s conviction would surface years later, when investigations into the use of jailhouse informants in Los Angeles County revealed many had been fabricating confessions in order to gain lighter sentences. Several informants said Storch taught them how to “book” other inmates by gleaning details about high-profile cases from newspapers and using that information to allege they confessed.

Some LAPD investigators had raised concerns about Storch’s reliability as an informant prior to Maxwell’s trial, according to court records. Storch was indicted on a perjury charge in 1988 as part of the investigation into the jailhouse snitch scandal, but died before he could stand trial.

Despite questions about Storch’s credibility, it would take more than two decades before the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals overturned Maxwell’s convictions.

While the court said it could not rule on the validity of Storch’s testimony about Maxwell’s confession, it did find Storch had demonstrated a “willingness to commit perjury.” The court also found Storch lied during the trial about his past as an informant and that he had received leniency in exchange for his testimony.

“Storch simply repeated facts about the Skid Row Stabber killings contained in a newspaper article he admitted to possessing, and he offered no details about any of the crimes that were not already public and in widespread print,” the ruling read.

News of the 9th Circuit decision brought a measure of relief to Maxwell’s family, who believed their long ordeal to prove his innocence was finally over.

“We all went through it. We went through hell. Stressing, you name it. My granny, every day she would ask me ‘Rosa, when is he coming home?’ ‘I don’t know, but he’ll be home soon.’ I always told my granny that,” Harmon said. “Even before she died she asked me, ‘When is Bobby coming home?’ ”

But in 2013, the district attorney’s office not only sought to retry Maxwell in the murders of Garcia and Jones, but obtained grand jury indictments in three of the slayings — those of Reed, Cortez and Drake — the jury deadlocked on in 1984. With the exception of Storch’s testimony, prosecutors presented the same information to the 2013 grand jury that they did at the original trial. Maxwell was denied bail.

Asked if the district attorney’s office still believes Maxwell was the only suspect, Grace said prosecutors have “never taken a position on whether there was a lone suspect.” Hayes said the LAPD remains convinced that Maxwell was responsible for all 10 killings, and declined to say whether he should be released.

“The doctors have indicated he would not recover from this,” Hayes said. “So, I don’t know that it serves any value and justice in continuing with it, but that’s up to the prosecution.”

Voluminous discovery requests and destruction of much of the evidence have delayed the case.

“The judge ordered live hearings on discovery issues. They went for over a year, during the course of which, thousands of pages of material were produced,” Alschuler said, adding that prosecutors provided several exculpatory statements that were not presented at the original trial.

Hayes said past investigators likely destroyed evidence in cases where a death penalty verdict had not been reached, or if the appeals process had been exhausted. In Maxwell’s case, physical evidence was destroyed in the three murders he was acquitted of. Some evidence in one of the cases he was convicted of was also destroyed.

Paula Mitchell, the legal director of the Project for the Innocent at Loyola Law School in Los Angeles, said the decision not to release Maxwell given his medical condition and the circumstantial evidence appeared “a little vindictive.”

“After he was able to prevail on appeal, to go back and charge him with things that the jury hung on? Given what we know now about the jailhouse informant scandal…It does cry out for some answers,” she said.

Alschuler said the district attorney’s office has both a moral and legal obligation to release Maxwell and allow him to live his final days with his family.

“It amounts to execution by false incarceration,” he said. “He just wants his name cleared.”

Follow @JamesQueallyLAT for crime and police news in California.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.