Taking the oath of office seriously to fight corruption in Southeast L.A. County

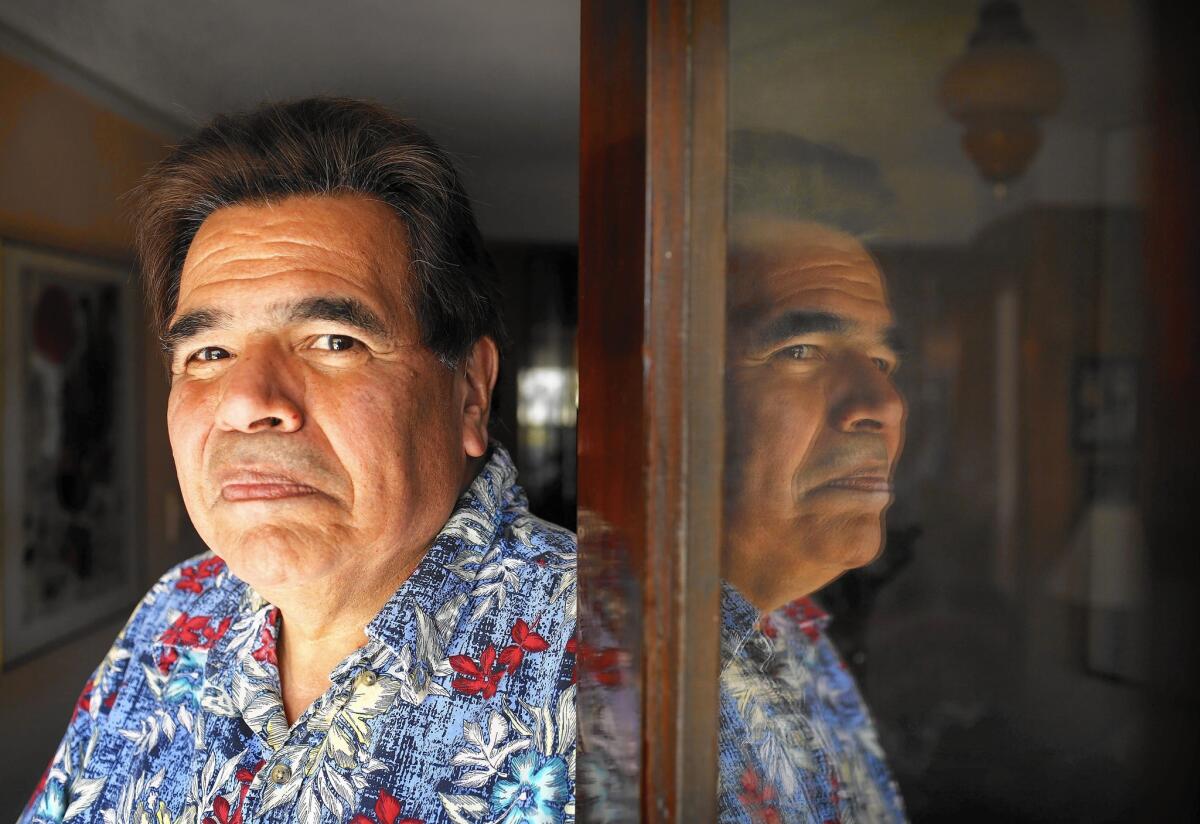

Richard “Ric” Loya, the former mayor of Huntington Park, helped the FBI bring down a corrupt casino owner.

Richard “Ric” Loya was in an unusually quiet mood, his car radio turned off as he pulled into the parking lot of the FBI offices.

He was 55, the mayor of Huntington Park and about to become an informant in a federal bribery case involving a local casino.

“What am I doing?” he asked himself.

That was 14 years ago, and Loya helped earn a corruption conviction.

Loya’s efforts were held up as a model for how local officials can fight the graft and greed that has long plagued the small, heavily immigrant cities that line the 710 Freeway south of downtown Los Angeles.

Many of these towns — Bell, Vernon, South Gate, Cudahy — have been scenes of major corruption scandals. In many of those cases, residents lamented that more elected officials didn’t come forward to report what was going on.

After the Huntington Park corruption case ended, the U.S. attorney issued a statement praising Loya for upholding the oath of his office and for doing “exactly the right thing by reporting this bribe attempt to the FBI.”

Loya used much the same words last month when he ran into Huntington Park Councilman Valentin Amezquita at a council meeting. Like Loya, Amezquita had recently played the role of FBI informant in a federal bribery case against the owners of a towing company.

“As a voter, it’s important to let an elected official know when they have done something good,” Loya said later. “And voters should let them know when they’ve done something bad too.”

Though the alleged bribes Amezquita received while working undercover were not very large — as in Loya’s case — experts say the amount of money involved is often beside the point.

“Whether the bribe is $5 million or $5, the action is the same. You’re saying: I’m in it for myself; I’m not in it to serve the public, and I’m willing to go around the rules and break the law,” said Jessica Levinson, a Loyola Law School professor. “It leads to a general dissatisfaction of government.”

In Southeast Los Angeles County, a region made up of a cluster of small, working-class cities such as Huntington Park, poor civic engagement by residents and political volatility have been the norm for years. Even intensely contested elections are often decided by a tiny number of voters.

Though this part of the county has been the focus of several prominent corruption investigations, L.A. County has 88 cities and it’s unclear whether municipal malfeasance is common elsewhere.

Last year, a pastor who worked as a management analyst for Pasadena was charged by county prosecutors with embezzling more than $5 million from the city over the course of a decade. The allegations against Danny Wooten were an embarrassment for an affluent city that prided itself on good government.

The L.A. County district attorney’s office declined to comment on the issue of municipal corruption, but former top prosecutor Steve Cooley said Southeast L.A. County generated the most complaints.

“We were so active down there conducting investigations, inquiries and prosecutions,” said Cooley, who started the district attorney’s Public Integrity Division. “We handled a number of complaints and resolved them. Some were unfounded and some were well founded.”

Cooley said there was no way to completely eradicate corruption, but that media attention, “an engaged and informed electorate” and skilled prosecutors were key to tackling it.

Several years ago, South Gate Mayor Henry Gonzalez said he was wrapping up a lunch meeting with a trash hauler at a Denny’s in Artesia when he felt an envelope pressed against his knee.

“I look inside the goddarn envelope and I see $100 bills. I got so upset,” Gonzalez recalled. He said he threw the envelope at the man’s chest, spilling some of the cash in the booth.

“I should turn you over to the law, man,” Gonzalez said he told the man before walking out.

Looking back, Gonzalez — who fought against a corrupt regime in South Gate years ago — said he should have reported the incident to authorities. He said he probably would have been asked to go undercover, like Loya and Amezquita.

“Most people seem to forget that when you’re an elected official, you are sworn in and you put your hand on the Bible and you vow to uphold the law of the state and the city,” said Gonzalez, who retired last year. “Any time you do anything to violate that you’re wrong. You violated your principles.”

In June 2001 Loya’s principles were put to the test when Harry Hwang, owner of LA Casino, paid him a visit at Huntington Park City Hall. According to Loya and federal authorities, Hwang offered to pay off Loya’s campaign debt, provide political contributions and pay for a family vacation to Italy in return for the mayor’s support of a measure that would forgive a $40,000 debt the casino owner’s business owed the city.

Loya reported the bribe to the FBI. Officials asked him to wear a wire the next time he met with Hwang. Going undercover was stressful, Loya recalls.

His mind raced: “Be careful what you say.” “What if the mic slips out?” “What if he figures it out?”

Loya said, “You feel lonely. There were things I couldn’t tell my wife.”

Loya said when Hwang was convicted and the case was over, he felt a sense of having done the right thing. But he also worried about retaliation. One day he found a bullet in the back of his BMW. He could never tie it to his undercover work, but it made him think.

For Amezquita, who has received praise from Huntington Park residents, the story is far from over. The owners of H.P. Tow Inc. have not been formally indicted on criminal charges.

A federal affidavit filed in October alleges that the men gave the councilman checks totaling $2,650 in exchange for his support on a measure that would allow them to automatically raise the fees they charge each year.

The checks came from friends, family and the two owners, all in an effort to avoid raising suspicion, according to the federal document. Amezquita secretly recorded conversations with the two men that took place at restaurants, on the phone and at the tow yard.

Amezquita has declined to comment about the case, but previously said in a statement to The Times that he took his oath of office and the rule of law seriously.

“I could relate,” Loya said of the councilman. “He did the right thing. It restored faith in government, for a while.”

Twitter: @latvives

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.