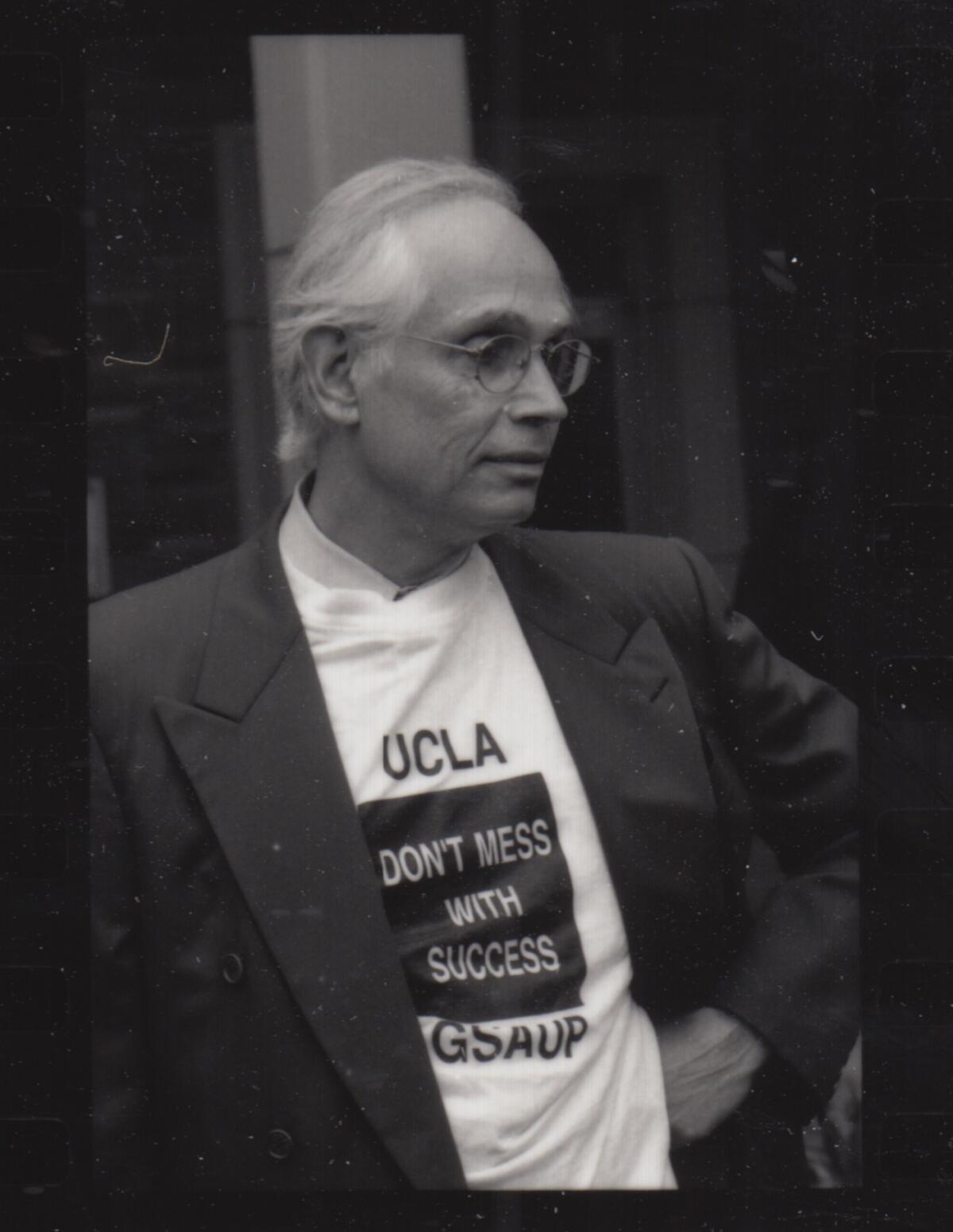

Richard Weinstein, who jumped from New York City politics to architecture deanship at UCLA, dies at 85

Los Angeles, Richard S. Weinstein liked to say, “is full of holes.” He meant it as a compliment — at least to a degree.

After working early in his career as an advisor on urban design to New York City Mayor John Lindsay, Weinstein, who died Feb. 24 in Santa Monica at 85, moved to Los Angeles in 1985 to become dean of the Graduate School of Architecture and Urban Planning at UCLA. After 10 years in that role, he spent another 13 as a professor in the department.

The city he found here was full of empty or under-developed space, with political power fragmented across a wide region — in contrast to the crowded spaces and even more constricted politics of New York.

“In Los Angeles, there is always a chance,” he told a reporter in 2008 with his trademark wry irony. “You can occasionally drive a great building into the gaps.”

In both his UCLA post and as a consultant and confidant to architects and patrons in Los Angeles, he tried to keep those gaps open and those great buildings coming. Weinstein served on the design jury that picked Frank Gehry as the architect for Walt Disney Concert Hall and as co-chair for the architectural selection committee of the Cathedral of Our Lady of the Angels, ultimately designed by Spain’s Rafael Moneo.

Anne Marie Burke of UCLA’s School of the Arts and Architecture confirmed Weinstein’s death and said the cause was “complications from a number of neurological and cardiac health issues.”

In a statement, UCLA credited Weinstein for championing “experimental West Coast architecture” and for putting the department “at the forefront of a movement to incorporate the burgeoning field of computer technology and robotics” into architectural education.

That’s true as far as it goes. But it was Weinstein’s political savvy above all that propelled his career on both coasts.

“Richard’s experience in urban planning and his work with the city of New York and New York government made him very helpful as an advisor to those of us who were starting to get more projects of a public nature,” Gehry said in an email. “He was a great counselor and was able to cut to the chase and get to the essence of what we were being asked to do.”

Samuel Richard Weinstein (he would later swap his first and middle names) was born Nov. 30, 1932, in New York City. After graduating from the Ethical Culture Fieldston School in the Bronx, Weinstein left New York City to attend the University of Wisconsin and then Brown University, where he earned a bachelor’s degree in 1954.

After earning a master’s degree in clinical psychology from Columbia, he turned to architecture, spending one year at Harvard’s Graduate School of Design before leaving to study under Louis Kahn, Robert Venturi and others in a master’s program at the University of Pennsylvania.

Weinstein blamed his quick departure from Harvard on his preference, in those days, for Frank Lloyd Wright over International Style modernism. “I decided I wanted to become an architect and got into Harvard,” he said in a 1994 oral history, and “was abominably treated because I brought Wright’s books into the drafting room and was told that was not permitted for a first-year student.”

Weinstein worked for architects I.M. Pei and Edward Larrabee Barnes and spent a year at the American Academy in Rome as a winner of the Rome Prize before joining the mayoral administration of the newly elected Lindsay in 1966.

Lindsay, who had a keen interest in architecture and urban planning, quickly established the Urban Design Group as part of New York City’s planning department. Weinstein worked there alongside a number of other young and ambitious architects and planners in close coordination with Lindsay’s policy guru, Donald Elliott. When Lindsay created new development offices for different parts of the city, he asked Weinstein to direct one covering Lower Manhattan.

Among the Urban Design Group’s most important initiatives were the sale of air rights above shorter buildings to developers who wanted to build higher elsewhere, generating revenue for the city, as well as so-called incentive zoning.

As Peter Blake wrote in a 1973 New York magazine article praising the urban-planning innovations of the Lindsay administration, “Private developers would be rewarded with virtual cash bonuses if they included theaters, or arcades, or shops, or ‘mixed uses’ (apartments as well as offices in a single building), or connections to mass transit, or other public spaces, in their developments. Most of these design tools were translated into city laws, and will help shape this city clearly for the better long after Lindsay.”

Those policies helped save South Street Seaport and revitalize Times Square, among other parts of Manhattan.

“When we left office,” Weinstein said in the oral history, “there were one hundred first-class architects working for the city.”

According to Dana Cuff, a UCLA professor of architecture and urban design, Weinstein admired Linsday for having “been so bold to let all these young men take over the city. Richard felt they really made a huge change in the way cities are planned.”

After helping plan and oversee the expansion of the Museum of Modern Art in the mid-1970s, a project that hinged on the transfer of air rights, Weinstein spent six years working on redevelopment along 42nd Street in Manhattan before making the leap to the West Coast.

At UCLA, he found that learning about politics and urbanism wasn’t always a top priority for students. “No matter what I try to do,” he said, “what the students want are the hot, cutting-edge designers. They’re not as interested in the social issues of the built environment, or political issues. They get interested later, when they’re professionals.”

In the end he split the difference between his priorities and those of the students. He promoted the work of many innovative, digitally minded L.A. architects, including Thom Mayne and Greg Lynn.

“He took me under his wing,” Mayne said. “He saw something in me. He decided I needed to do certain things and that I was going to do them. He coached me. He critiqued me.”

Weinstein founded the Lewis Center for Regional Policy Studies at UCLA and immersed himself in political debates over architecture and planning in Los Angeles. Along with Mayne and Cuff, he recruited Sylvia Lavin, Craig Hodgetts and Mark Mack to the UCLA faculty. He led one of the committees helping to prepare the “L.A. 2000” report for Mayor Tom Bradley, published in 1989, on the city’s future.

He also continued his architectural work, contributing to the design of the Temple Kehillat Israel in Pacific Palisades and the Westside Children’s Center, among other projects.

What he liked most was to be in the middle of the action, whispering in the ears of elected officials, prominent architects and architectural patrons such as Eli Broad. He enjoyed working on civic projects not despite but sometimes because of the red tape they came wrapped in.

“Kind of like [the artist] Christo, he took great pleasure in the bureaucratic achievements that made the thing possible,” Cuff said.

Sam Hall Kaplan, writing in The Times about Weinstein’s rumored arrival at UCLA in 1985, noted his reputation as “a hard-headed, action-oriented urban designer very much involved in the shaping and misshaping of cities.”

Mayne described him differently: “He was a New Yorker through and through, but he had a great twinkle in his eye. He was a provocateur, but never just for the sake of provocation. Only to move the world forward.”

By the time Weinstein left the UCLA deanship, the architecture and urban planning programs had split apart, a change that disappointed him.

“He never really overcame that,” Cuff said. “He felt UCLA didn’t understand his vision and the vision he carried over” from his predecessor as dean, Harvey Perloff.

Weinstein continued to be fascinated by the urban form of Los Angeles and all the ways it was distinct from the New York streetscapes he knew so intimately. He saw L.A.’s openness, both physically and temperamentally, as its great distinguishing characteristic.

“We live in a city where there is more space than buildings — unlike Paris, London or New York, where public spaces, such as streets and parks, are carved out of a mass of buildings,” Weinstein wrote in an op-ed for The Times in 1997.

He never lost his interest in architecture’s public role, especially the way prominent buildings meet the civic realm. In 1989, when Pei and Henry N. Cobb’s Library Tower (now the U.S. Bank Tower) opened as the tallest building on the West Coast, Weinstein told The Times he was more concerned with how it looked from the sidewalk than in the skyline.

After all, he said, “the top 60 feet belongs to a few people. The bottom 60 feet belongs to everyone.”

Weinstein was “the last of an era,” Mayne said. “He thought of architecture as a noble profession. Can you imagine?”

Weinstein is survived by his wife of 34 years, Edina; two sons from an earlier marriage to Sandra Cohen; and two granddaughters.

christopher.hawthorne@latimes.com

Twitter: @HawthorneLAT

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.