Watch Muslim kids read letters from Japanese internment camp survivors

The Japanese American children who spent years in World War II internment camps were hopeful.

Some thought racial discrimination would end after the war, they wrote in letters about their daily lives. But now, the grown-up survivors are seeing another group endure isolation and hatred: Muslim Americans.

That link is illustrated by the Muslim American children, ages 7-13, in filmmaker Frank Chi’s video, as they read the letters aloud with internment camp survivors (not the writers of the original letters).

The Smithsonian Asian Pacific American Center posted Chi’s video on its Facebook page this week. It’s part of a Memorial Day exhibit called CrossLines: A Culture Lab on Intersectionality, and it’s meant to remind people that hateful words aren’t just words — they can cause real fear and harm.

In a November statement arguing against allowing Syrian refugees into the country, a Virginia mayor referenced the internment camps. After the San Bernardino terrorist attack and since, Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump called for a ban on Muslims entering the U.S.

Camp survivors say this language is too similar to what they heard decades ago.“If you ask me, 'Could this happen again to youngsters?' The answer is absolutely yes," said Rep. Mike Honda (D-San Jose). “When we let down our guard as citizens and political leaders ... bad things happen."

------------

FOR THE RECORD

7:22 a.m.: An earlier version of this article identified Rep. Mike Honda as (D-Walnut Grove). The designation should have been (D-San Jose).

------------

Honda is one of the Japanese camp survivors who appears in the video, next to 11-year-old Zaid Syed, from Virginia.

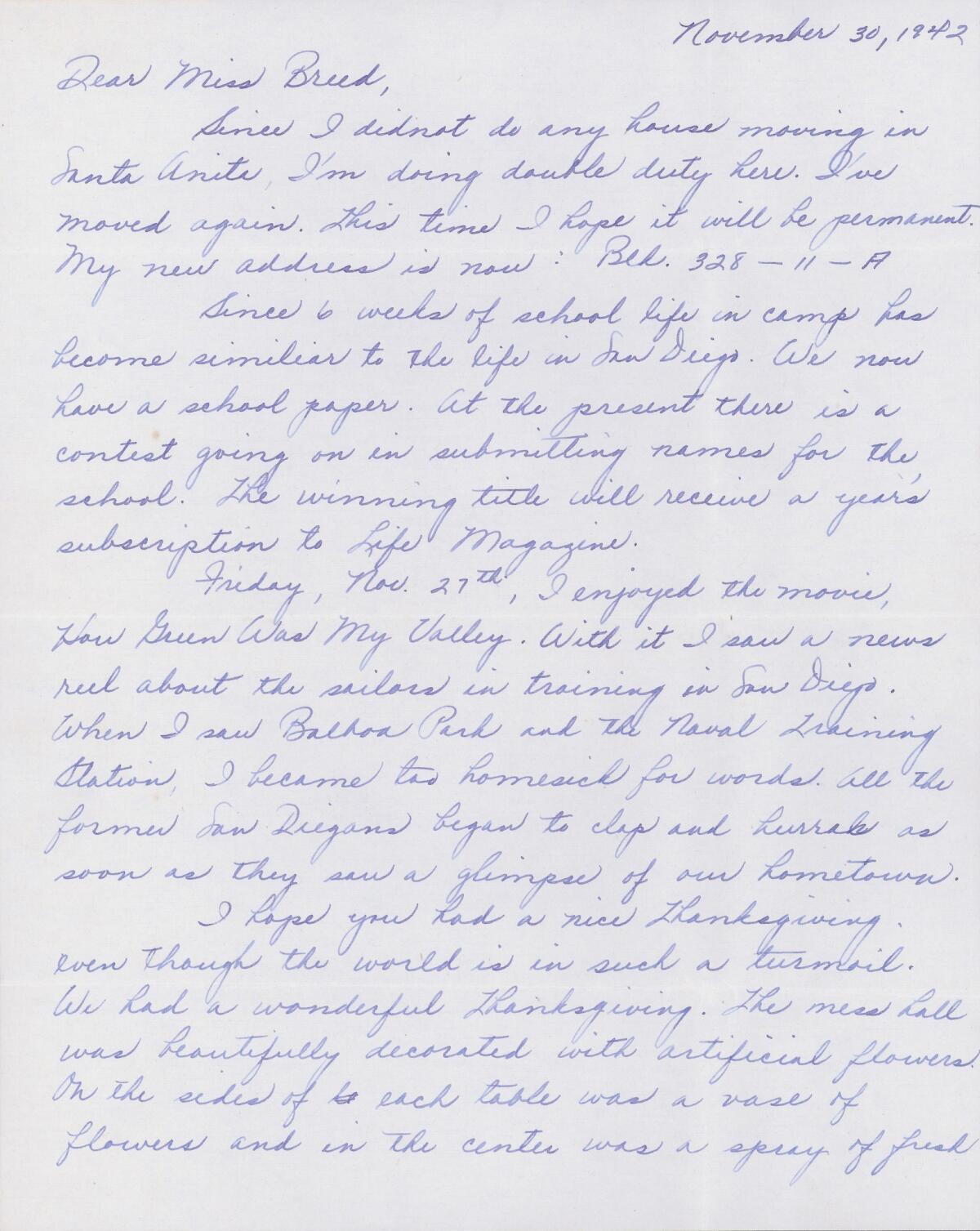

In the video, Zaid reads part of a letter that a girl named Louise Ogawa sent in 1942.

"One discouraging thing which occurred here is the building of the fence," Zaid reads, standing next to Honda in front of the American flag. "Now there is a fence all around this camp. I hope very soon this fence will be torn down."

This video is one form of speaking out against hateful rhetoric, Honda said.

That's the lesson Saba Baig wanted to teach her son Zaid, when she agreed to let him be a part of the video.

Baig was born in 1976 to parents who grew up in Pakistan and raised her in New Jersey. She remembers multiculturalism being celebrated at her school, but that feeling of acceptance has changed in the last decade.

------------

FOR THE RECORD

7:07 a.m.: An earlier version of this article stated that Saba Baig was born in 1986. She was born in 1976.

------------

Last year Baig was with Zaid and other family members at an ice cream parlor, when a man noticed her hijab and began telling the family that they should be Christian and that their children would die and go to hell, she said. Other patrons chased the man out of the shop, and the manager called police.

But before someone intervened, Baig saw that her children "had fear in their eyes."

This video, Baig said, was a way to teach her son how to combat hate in a positive way.

Where did the letters come from?

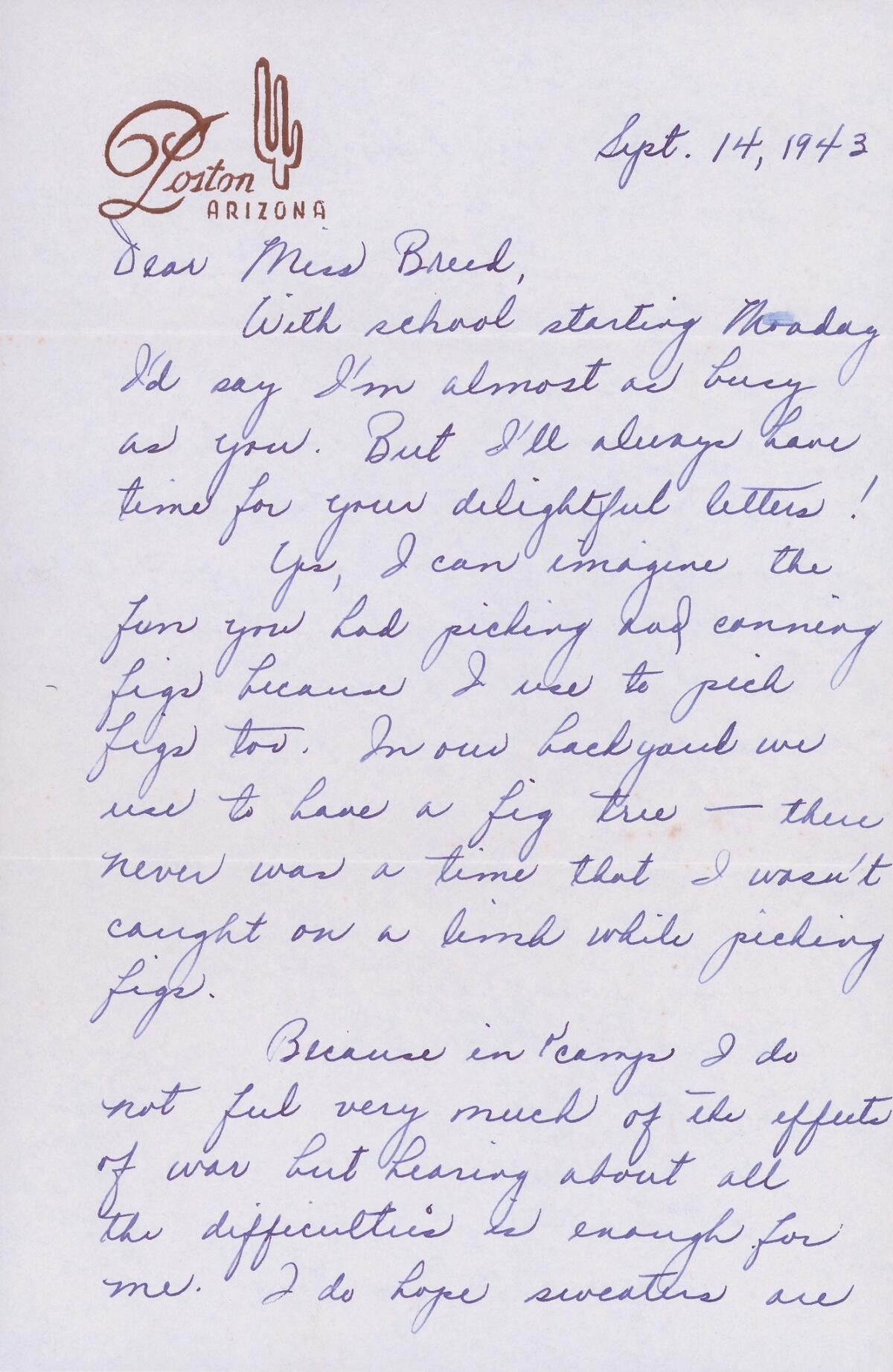

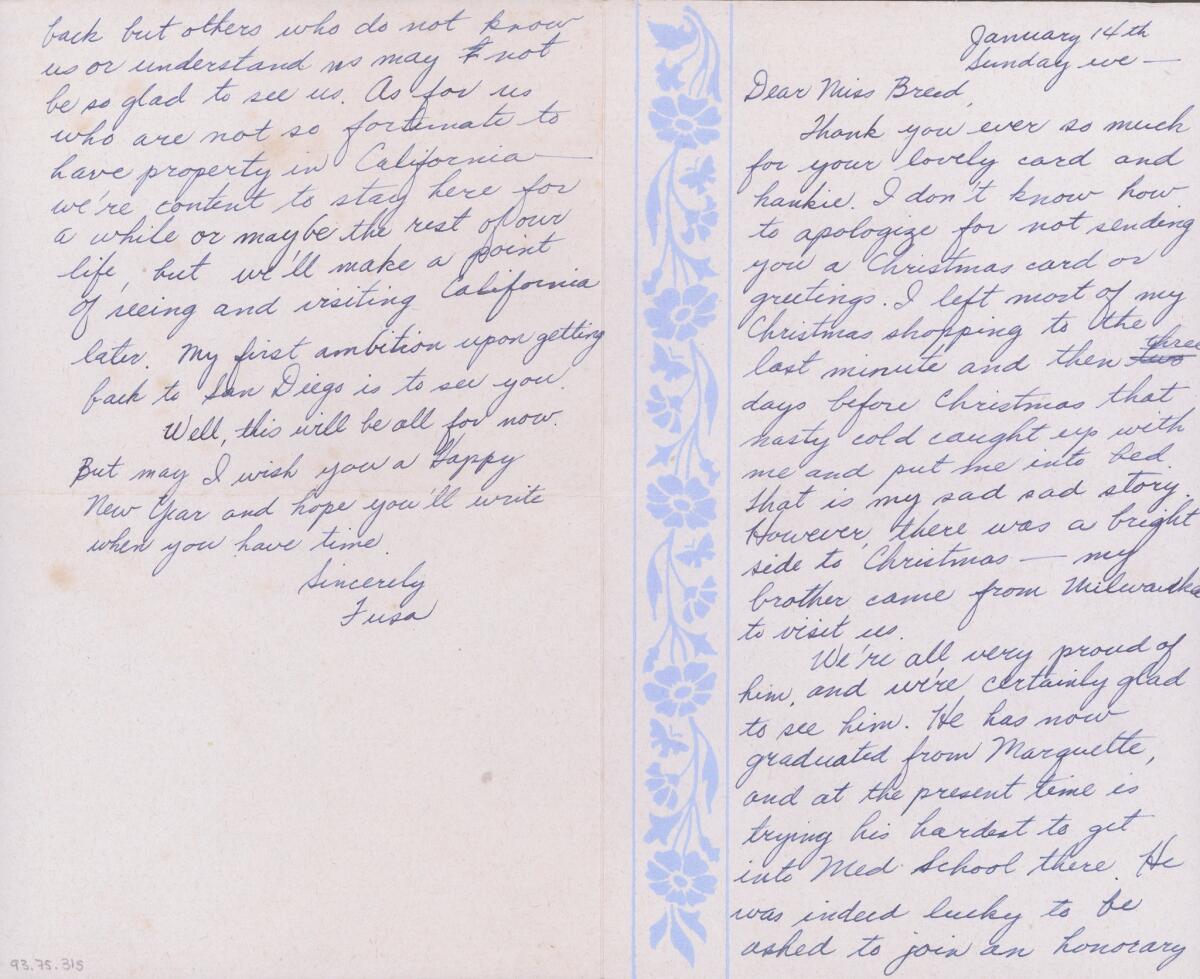

In the 1940s, as Japanese American families were being rounded up and sent into years of imprisonment, a librarian in San Diego named Clara Breed gave children paper and ink and stamps. She told them to write to her, and she sent them books and letters.

Chi came across the collection of letters on the Japanese American National Museum's website. The museum, in Downtown L.A., houses the collection in an archive.

The letters discuss life in the camps, what the children hoped for upon their release, how they wanted America to look.

"I am sure when this war is over there will be no racial discrimination," reads one letter, "And we won't have to doubt for a minute the great principles of democracy."

The video includes six pairs of children and Japanese elders, reading from three different letters: two from from Louise Ogawa in Arizona and one from Fusa Tsumagari in Minneapolis.

Breed is a beloved figure in the Japanese American community, said Greg Kimura, president and chief executive of the Japanese American National Museum.

------------

FOR THE RECORD

10:08 a.m.: An earlier version of this article omitted a full identification of Greg Kimura, president and chief executive of the Japanese American National Museum.

------------

She was a representative of mainstream America who made sure these children knew that their thoughts mattered, Kimura said.

Chi shot most of the video in the Menlo Park home of Claire Haratani Chambers, an 89-year-old who was incarcerated in camp as a teen. Six family members went from a three-bedroom Santa Clara house on a 10-acre farm with walnut trees and raspberries into one room, first at Santa Anita and then in Heart Mountain, Wyo.

"When we left [home], no one was at the station to say goodbye to us," said Chambers, who had no one to send letters to. " Clara Breed "was very courageous and very thoughtful.”

Though the letters aren't currently on display at the museum, they are online.

Chambers wants people to see this video to understand what children like her went through because other Americans make judgments based on religion or race.

“It happened once," she said. "It should never happen again."

Reach Sonali Kohli at Sonali.Kohli@latimes.com or on Twitter @Sonali_Kohli.

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.