Man learns his true identity after having amnesia for 11 years

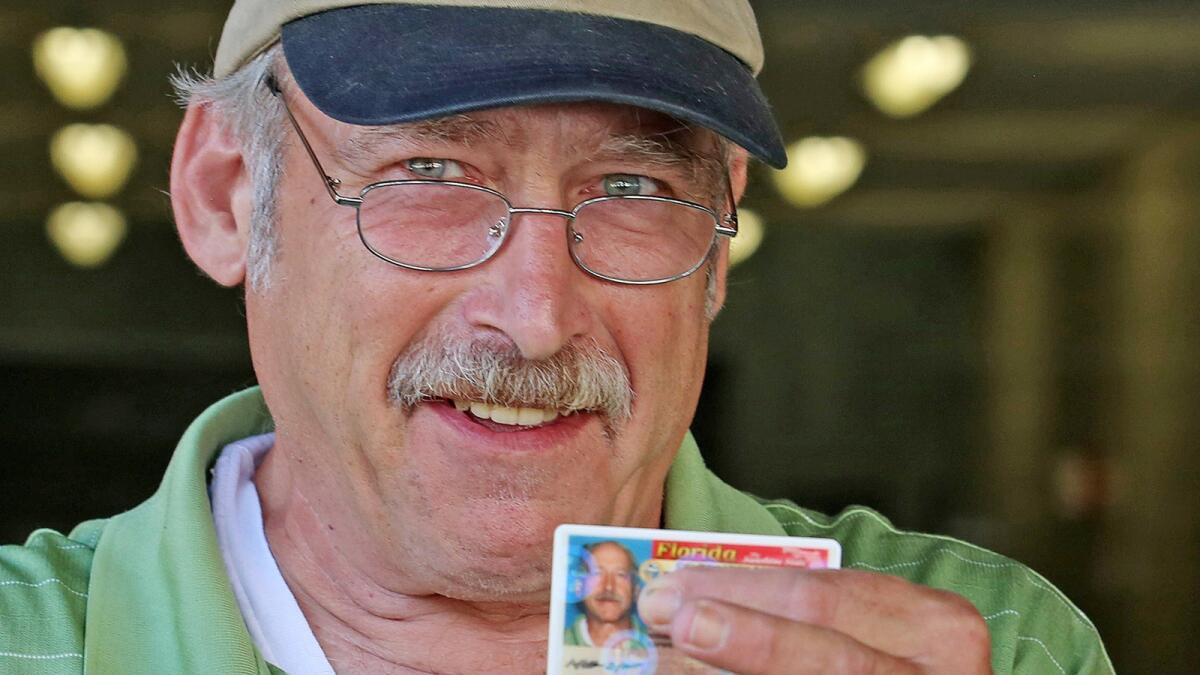

Benjaman Kyle places his fingers over his real name on his newly issued Florida ID card in September.

The man who can’t remember his past came to Orlando in search of a future.

For more than a decade, he called himself “Benjaman Kyle,” because he didn’t know his real name.

“It was like I was a ghost,” he said. “Legally I didn’t exist.”

Kyle, whose extraordinary ordeal has been featured on “Dr. Phil,” CNN and in National Geographic, was diagnosed with retrograde amnesia 11 years ago when he was found unconscious behind a Burger King in Georgia.

The cleaning woman who found him near the restaurant’s dumpster told a dispatcher in Richmond Hill, a suburb of Savannah, that she thought he was dead. He was naked and covered with fire-ant bites.

Police found nothing to identify him and called paramedics to take him away, figuring he was homeless.

When he awoke, he couldn’t help authorities solve the mystery.

One of the only biographical facts he recalled was his birthday: He was exactly 10 years older than pop singer Michael Jackson.

“You see it in the movies: Someone gets conked on the head and they forget everything. Oh, yeah, right,” said Jacqueline Dowd, an attorney with IDignity, an organization that helps homeless and other low-income people get government-issued identification.

“But in this case, it’s true. We’ve seen the medical records that prove he does have that condition.”

IDignity invested more than two years helping Kyle collect documents needed to prove he wasn’t a ghost.

DNA testing, meanwhile, proved recently that he wasn’t Benjaman Kyle either.

While in the hospital, he had assumed the name Benjaman Kyle partly because the hospital staff had dubbed him “B.K.” Doe — for Burger King — and partly because he thought Benjaman sounded vaguely familiar, though it’s usually spelled “Benjamin.”

A YouTube documentary titled “Finding Benjaman” explores his rare condition, his quest for his identity and the struggle to live in the United States without a government ID.

The film begins: “Hello, my name is Benjaman Kyle. You don’t know who I am and, quite frankly, neither do I.”

It also claims Kyle was the first U.S. citizen whose whereabouts were known, but who nonetheless was listed on the FBI’s kidnapped and missing persons database.

His fingerprints turned up no criminal record.

In the 2012 documentary, Kyle said, “It’s pretty pathetic if no one’s actually looking for someone that disappeared. Isn’t there anyone important enough in your past life that would want to look for you?”

NEWSLETTER: Get the day’s top headlines from Times Editor Davan Maharaj >>

A team of genetic genealogists, led by CeCe Moore of theDNAdetectives.com, finally helped him learn his true identity.

The method was similar to a procedure developed for adopted people who want to identify their birth families.

The genealogical team compared Kyle’s DNA to records in databases across the country to find clues, determined his most likely ancestral bloodlines by cross-checking and using a process of elimination, and eventually located an older brother in Indiana.

“It was so wonderful to finally see all the pieces come together for him,” Moore said.

Kyle, 67, could have obtained his state ID card anywhere in Florida but chose Orlando because it’s home to IDignity, which helped him cut through red tape to regain his legal identity.

The organization often tracks down lost birth certificates, original Social Security records and other documents, some of which have to be amended because the names on the paperwork do not match precisely — and they have to, attorney Dowd said.

“To assemble the documentation necessary for a name he hasn’t used in over 10 years took some doing,” she said.

Michael Dippy, IDignity’s executive director, said government-issued identification is essential to American society.

Kyle, for instance, could work only “under the table” because he couldn’t get one.

“Without it, you can’t apply for a job, collect government benefits, sign a lease, enroll in school, get a library card, write a check, cash a check and, in some places, you can’t even stay at a homeless shelter,” Dippy said.

Kyle said he won’t reveal his true identity until he meets with relatives in Indiana, his birth state.

Some may have thought he was dead.

He obtained his Florida ID card, aided by IDignity, which paid the $31.50 state fee.

The laminated card, which includes a hologram as a counterfeiting deterrent, features his picture, which he said looks “terrible,” and his birth name.

Kyle described the ID card as “a big turning point” in his struggle and said, “I now exist — and can prove it.”

He said he intends to have his Social Security number tattooed on his backside — as a precaution.

ALSO:

Pet micro pigs? Chinese biotech firm says it will sell very small swine

Oregon sheriff wrote, ‘Gun control is NOT the answer,’ and residents agree

Nobel Prize in medicine goes to 3 scientists for work on parasite-fighting therapies

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.