Q&A: Customs and Border Protection chief discusses new era of transparency

When R.

The U.S. Border Patrol is one of the country’s largest law enforcement agencies, with 21,000 agents. It has faced recent scrutiny not only for multiple incidents concerning its use of force, but also its lack of transparency in handling those cases.

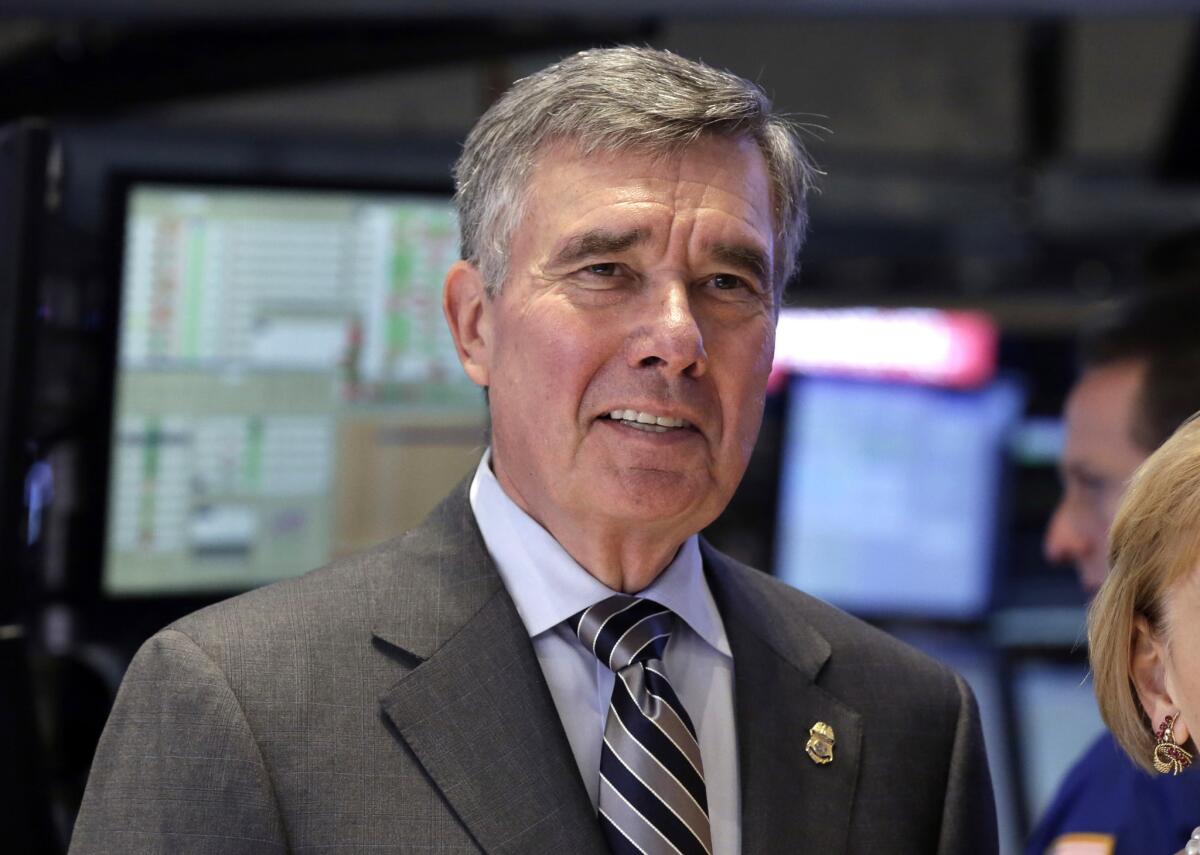

When R. Gil Kerlikowske became commissioner of Customs and Border Protection — which oversees the Border Patrol — in March 2014, he promised a new culture of openness.

He has largely delivered on that pledge, directing sector chiefs and their communications staffs to issue a statement within 12 hours of an agent’s use of lethal force.

Still, it took several days earlier this year for the Border Patrol to tell The Times the fate of a suspect shot by an agent in January.

Neither the media nor the public nor the nonprofits are going to allow Customs and Border Protection to go back to ‘no comment’ and ‘it’s under investigation.’

— R. Gil Kerlikowske, Customs and Border Protection commissioner

“We should be able to tell you if he is wounded and alive or dead,” Kerlikowske said in an interview that has been edited for clarity and space.

You’ve said that Border Patrol agents are used to being alone in the field without backup nearby and that now they have to get used to working near large population centers. How must they change what they do?

When you think about the geography of where they work and the number of people that they could encounter, the backup, the lack of radio equipment — that’s a different culture from any law enforcement agency anywhere in the United States.

I’ve told Border Patrol recruit classes, there’s no apprehension, there’s no seizure of drugs, there’s no pursuit of a vehicle that’s worth you getting hurt for. And that’s a hard change.

What kind of training is different now for the agents, given the ways you’re asking them to change?

Even with backup and someone else close by, it can still be quite dangerous and things can happen in the blink of an eye.

We like the fact that they’re expanding the training out here in the academy in New Mexico, and it’s much more scenario-based than classroom lecture. The de-escalation techniques that law enforcement has been teaching are being reflected in those scenarios.

Sometimes when an agent uses lethal force, the Border Patrol doesn’t disclose certain details that would be disclosed in an identical shooting by another agency, such as the name of the agent, the name of the subject and circumstances surrounding the shooting, including whether the wounded person is still alive. Are you telling the public enough when it comes to uses of lethal force by Border Patrol agents?

Are we telling the public enough or are we telling reporters enough? [Laughs] Our constraints are a little bit different [from a county sheriff’s office]. We have to be very mindful of playing by the rules of the Department of Justice in the criminal process.

It’s a large organization. It takes a little while to not only change policy but to have it drilled down into everyone.

Sometimes, in vast areas like Cochise County, Ariz., which is the size of Connecticut, or La Paz County, Ariz., which is the size of Rhode Island, residents will turn to the Border Patrol instead of the local sheriff’s office because the Border Patrol agents are closer. When the Border Patrol is acting in that kind of surrogate law enforcement capacity, and ends up using lethal force, is there some obligation to disclose more than even the updated statements?

We depend on state and local law enforcement as much as they depend on us.

Our restrictions as a federal law enforcement agency and what we can do and what we can enforce are different, so we don’t want to be seen at all as a primary responder to the needs of local law enforcement or the community.

Does the administration support your efforts? What happens when President Obama leaves office?

I’ll leave at the end of the term. I’ll tell you, quite frankly, they’ll never go back to the way it was. Neither the media nor the public nor the nonprofits are going to allow Customs and Border Protection to go back to “no comment” and “it’s under investigation.”

[Current executive staff members] are all still going to be there after I leave. They’ve all been schooled in this. I don’t see any administration turning the clock back on transparency.

Are you comfortable with the level of experience among agents since the massive staffing ramp-up of the Border Patrol in the mid-2000s?

The vast majority did a good job, but the hiring standards should have been more stringently applied. [Today] I’m very satisfied with the hiring standards; I’m not very satisfied that we have 1,200 open positions.

The Homeland Security Advisory Council recently recommended that agents be equipped with body cameras, which the Border Patrol has rejected in the past. How hard will it be to get agents to accept cameras?

It’s a negotiable issue with the union, and I think the union has made it clear they would be supportive of cameras. The agents that field-tested them were satisfied with them.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.