In Hawaii, life goes on under the volcano, even as it spews lava and threatens to explode

David Hess Jr. stood with about 20 people early Saturday morning under a large tent, which was protecting big bags of rice, donated clothes and canned food.

Except for the light drizzle tapping on the plastic tarps overhead, it was quiet. No one spoke. All eyes were fixed on Ikaika Marzo — a tall man with a thick, dark head of hair that made him appear even taller.

“Today is not going to be a normal day,” said Marzo, who was leading the group of volunteers. “There’s a new fissure. If gas comes over Highway 132, we’re going to have to move out of here quickly. For now, we’ll stay as long as we can.”

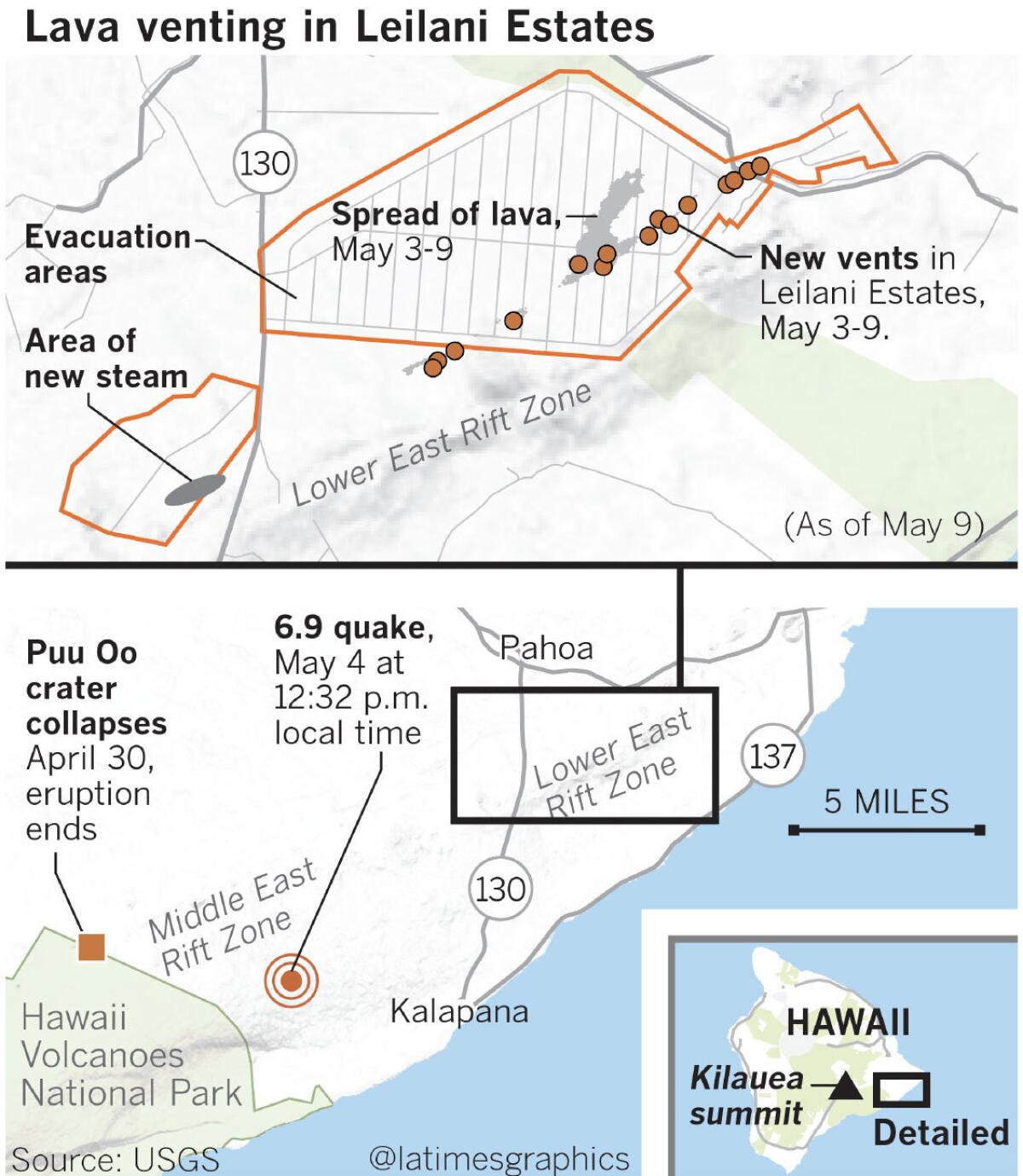

It was the 16th fissure to open, scientists confirmed Saturday.

Hess shifted his weight on his feet uncomfortably. He knew what might be coming because he’d seen it all firsthand a week earlier when Kilauea erupted and the earth opened up in his neighborhood, spewing fountains of fire and pushing a slow stream of lava to the edge of his house in Leilani Estates.

The group of volunteers who had been handing out donated supplies to about 2,000 evacuees from the region joined hands in a prayer circle. Hess closed his eyes as they asked God for protection.

And that’s about all one can do now. You can ride out a tornado in a cellar, or watch a flood from higher ground. But flowing lava? You wait and watch and worry. Or, like Hess, you try to do something to keep busy and help.

After the prayer, they ate a quick breakfast — French toast, fruits and coffee. Marzo said they had to load up a trailer in case they had to evacuate again. Hess got on his phone.

“I’ll call my family to help,” he said. “That’s about 30 people right there.”

Leilani Estates is a small rural community just outside Pahoa, where the relief supplies were being kept and evacuees had been gathering since the May 3 eruptions and earthquakes, including one 6.9 magnitude. In the last nine days, people who have lived with Kilauea’s constant but mild eruptions for 35 years are casually antsy.

While the walls of lava that have blocked streets are dramatic, that's not what triggers fear. That comes from below, where it seems at any moment a crack could open up and magma could start shooting out with all the warning and spontaneity of a jack-in-the-box.

We knew we were living on a volcano. We know what to do.”

— David Hess Jr., Leilani Estates resident

Hess said most places have their own natural disasters — tornadoes, fires, floods. Hawaii is no different.

“We knew we were living on a volcano,” Hess said. “We know what to do.”

For those who don’t live in Hawaii, the volcano eruption seems to be viewed by some as a potential Pompeii-like disaster that could destroy the island. Images of lava seeping across streets, engulfing cars and swallowing up homes — leaving piles of hardening black lava still smoldering and smoking in its wake — have exacerbated worries among tourists.

President Trump on Friday declared it a major disaster, freeing up federal assistance in affected areas. David Mace, a spokesman for the Federal Emergency Management Agency who was on the ground in Hawaii, said the agency staff would be there “as long as it takes.”

But Leslie Gordon, a spokeswoman for the U.S. Geological Survey, also felt compelled Saturday to provide perspective and quell uncertainty among travelers who were planning to go to Hawaii.

“The hazard is pretty localized just to Kilauea volcano,” she said. “Not to the rest of the island and certainly not to the rest of the state.”

The main community affected is Leilani Estates — the “estates” part being a bit of a misnomer. This isn’t a community of mansions. It's a mix of homes on large plots of land, separated by patches of heavy vegetation, with a counter-culture, hippy vibe. There’s a homeowners association rule against keeping chickens or ducks. It’s widely ignored.

Pahoa, a small and mostly rural town, was where Hess was spending most of his days since being forced to leave his house. He had returned twice to recover items he couldn’t get during the initial evacuation when he stood wide-eyed at the wall of lava moving methodically like a fiery version of “The Blob” toward his house.

When Hess and his family escaped, they piled into his truck. So did four dogs. But one, a small black-and-white terrier named Puna, jumped out. Hess was sure Puna didn't make it. But when he returned to the house to gather some things a few days later, he found Puna by the house. Alive.

On Friday, he helped Iyra Haas load up a few things in Haas’ truck — surfboard, mirrors and some metal racks — while a few other neighbors walked down the road to see up close a few steaming fissures. Hess couldn’t reach his house from the road, Luana Street, so he had to hike through a thick, jungle-like forest filled with fire ants to reach it.

When he emerged from the vegetation, he stopped for a moment and gazed at the fresh, black mountain range of steaming lava that had come to a halt in his frontyard.

Then he walked around the house, noting the foundation had separated from the driveway. Large cracks zigzagged on the pavement around his house and on the concrete deck of the outdoor pool. He marveled that none of the windows were broken. The air was smoky, reminiscent of a fire pit, but not as pleasant. It stung the eyes.

Inside his house, he walked past a piece of paper tacked on the wall. “Home Escape Plan,” it read.

“We drew that up last year,” Hess said. On another wall were the measurements of his grandchildren — the last one marked Feb. 16. On the fridge was a picture of Kenden, his 4-year-old nephew who died of leukemia.

“We kept his ashes in the house here — along with a bunch of photos we had,” Hess said. “We took him with us that first day. We weren’t going to leave him here.”

Hess said he wouldn’t leave his parents’ ashes, either. Both had died in the house. They were among the first things he grabbed.

He picked his way through the house, seeing what he could fit in his Philadelphia Eagles backpack. In the entertainment room, where he watched Eagles games, he grabbed a certificate that noted he had attended his first Eagles game against the Washington Redskins on Oct. 23, 2017. Above it was a sign that read, “Dear Santa: All I want is for the Eagles to win the Super Bowl. Thank you.”

Carefully, he put the certificate in the backpack.

Hess had been diagnosed with cancer in 2014 — Stage 3 melanoma. He had several operations as it had spread to the lymph nodes. He said that was a wake-up call for him to start trying to knock off bucket list items — one of which included attending a home game of his beloved Eagles, on their way to winning Super Bowl LII in February.

“We saved for a year for that trip,” he said, walking out the door and facing the mountain of lava again. “I tell my family now that if they can do something like that, they can do it. You have to chase those dreams.”

But right now, he can barely look to the next day, let alone the Eagles’ upcoming season. That’s why he volunteers at the relief center, working for Marzo.

“I need to keep my mind busy,” Hess said.

That has meant working long days handing out items to evacuees, some of whom are sleeping on cots at the Pahoa Senior Center and will walk up the narrow road past Pele’s Kitchen, the New York Pizzeria and Jan’s Barber and Beauty Shop to the lot where the donations are dropped off and picked up.

A man with a long white beard who walked with a limp drove his beat-up pickup truck into the lot to donate dried milk. A few others left clothes. Marzo said water was the item given out the most, however.

Jeff O’Neill had walked from the senior center to pick up some blankets for his son, Shaun O’Neill — a 37-year-old who suffers from ankylosing spondylitis and uses a wheelchair.

Both men voluntarily evacuated from their home after a big second earthquake struck. Jeff O’Neill said it was the first time his son had left the house in years. He had to carry him out, carefully balancing on a row of two-by-four planks that dropped down at an angle from the small studio-like home on stilts. A longtime surfer, he felt confident he could keep his balance during the descent.

“I was calmly moving swiftly,” Jeff O’Neill said.

Shaun O’Neill said when the lava began bleeding out of the earth, “it was the smell of hell.”

“I wanted to get out of there,” he said.

Hess said he planned to keep working at the volunteer center because he wants to help others — just as he did when he went to the Gulf Coast of Mississippi to work with those displaced by Hurricane Katrina.

This time, however, it’s his own community. It’s home.

Twitter: @davemontero

Produced by Sean Greene

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.