After two decades, the Kennewick Man is reburied

On a summer day in 1996, a pair of college students walking along the Columbia River in Kennewick, Wash., stumbled upon part of a human skull, about 10 feet from the shore.

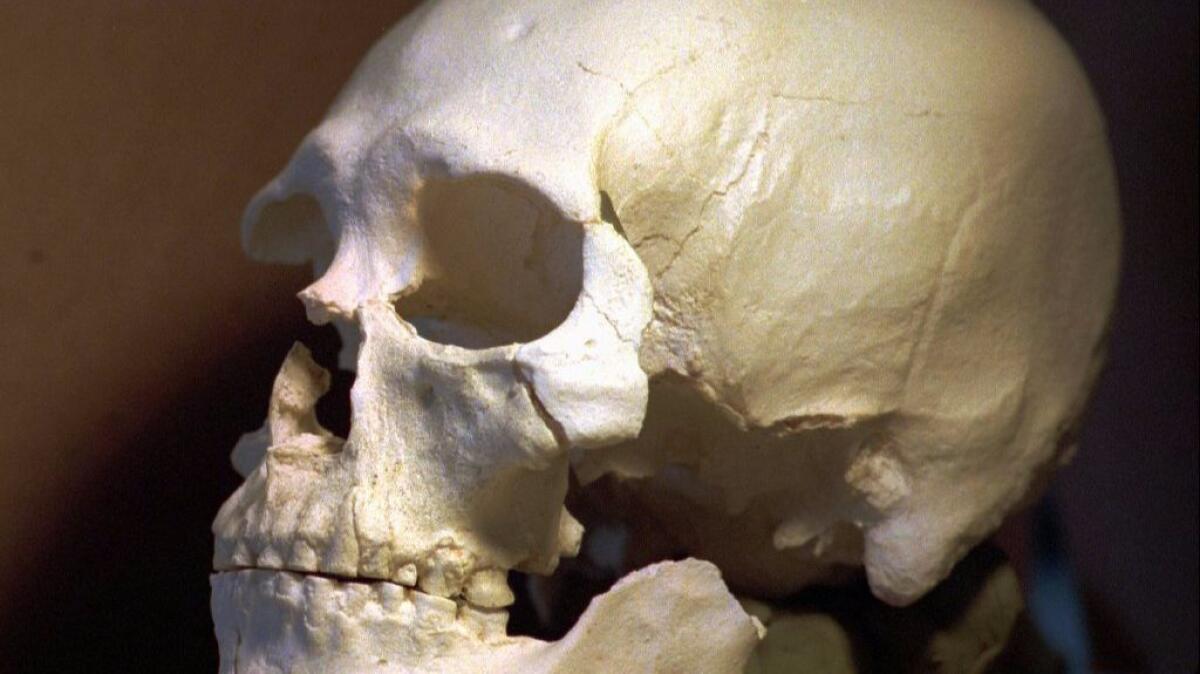

In the month that followed, investigators unearthed 300 pieces of bone that made up one of the oldest and most complete skeletons ever discovered in North America.

The discovery, known as Kennewick Man, launched a lengthy legal dispute between scientists and Native Americans over the origins of the remains and what to do with them.

The 20-year saga came to an end over the weekend when the 9,000-year-old skeleton was brought home and laid to rest.

On Friday, about 30 members of five tribes traveled to the Burke Museum in Seattle — where the skeleton was housed for nearly two decades — to retrieve dozens of boxes holding the remains. The next morning, more than 200 members of those tribes — the Yakama, Umatilla, Nez Perce, Colville and Wanapum — gathered privately at a secret location in the Columbia Basin to bury the man they call the Ancient One.

“The Ancient One … may now finally find peace, and we, his relatives, will equally feel content knowing that this work has been completed on his behalf,” JoDe Goudy, chairman of the Yakama Nation Tribal Council, said in a statement.

When the bones were discovered, scientists believed that they were unrelated to Native Americans and wanted to study them for clues about how people arrived in North America. The researchers suggested that Kennewick Man was a descendant of people who migrated from Asia into North America earlier than the populations that gave rise to modern Native Americans.

It was a controversial idea because it challenged the widely held notion that the tribes were descendants of the continent’s original inhabitants.

The tribes held that Kennewick Man was an ancestor and sought custody of his remains for reburial, arguing that further research would be a violation of their religious and cultural rights.

A prolonged legal battle followed, with scientists eventually persuading the courts that Kennewick Man’s skull more closely resembled those found in people from Japan and Polynesia than those of Native Americans.

The tribes lost the legal fight in 2004, when a court ordered that the skeleton was to remain in the museum under the auspices of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. Researchers were allowed to study the remains at the museum, while the tribes also visited to hold ceremonies.

Once the technology became available, scientists extracted the Kennewick Man’s DNA from a tiny piece of bone and compared it with DNA from people from Europe, Asia and the Americas — including two members of the Colville tribe in Washington state, one of the groups that had claimed the remains.

The results, published in 2015, revealed that Kennewick Man shared the most DNA with Native Americans, confirming what the tribes had maintained all along: He was a long-lost relative.

“We always knew the Ancient One to be Indian,” said Aaron Ashley, an Umatilla board member. “We have oral stories that tell of our history on this land, and we knew, at the moment of his discovery, that he was our relation.”

In December, President Obama signed legislation that required that the remains be returned to the tribes of eastern Washington.

The move was “the right decision” and “long overdue,” Burke Museum officials said in a statement, citing a federal law that allows tribes to reclaim human remains and cultural artifacts from museums and institutions.

Goudy, the tribal leader, vowed to fight for the return of countless other relatives, artifacts and possessions “that lie within various collections, amongst various entities, governed by various laws.”

“Our work will continue on their behalf because they must be returned to their appropriate resting place,” he said. “We must fix the governing laws that allow such disrespect to continue to be dictated to our collective peoples.”

alene.tchekmedyian@latimes.com

Follow me on Twitter @AleneTchek

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.