Revised U.S. history curriculum addresses criticism, but conservatives still object

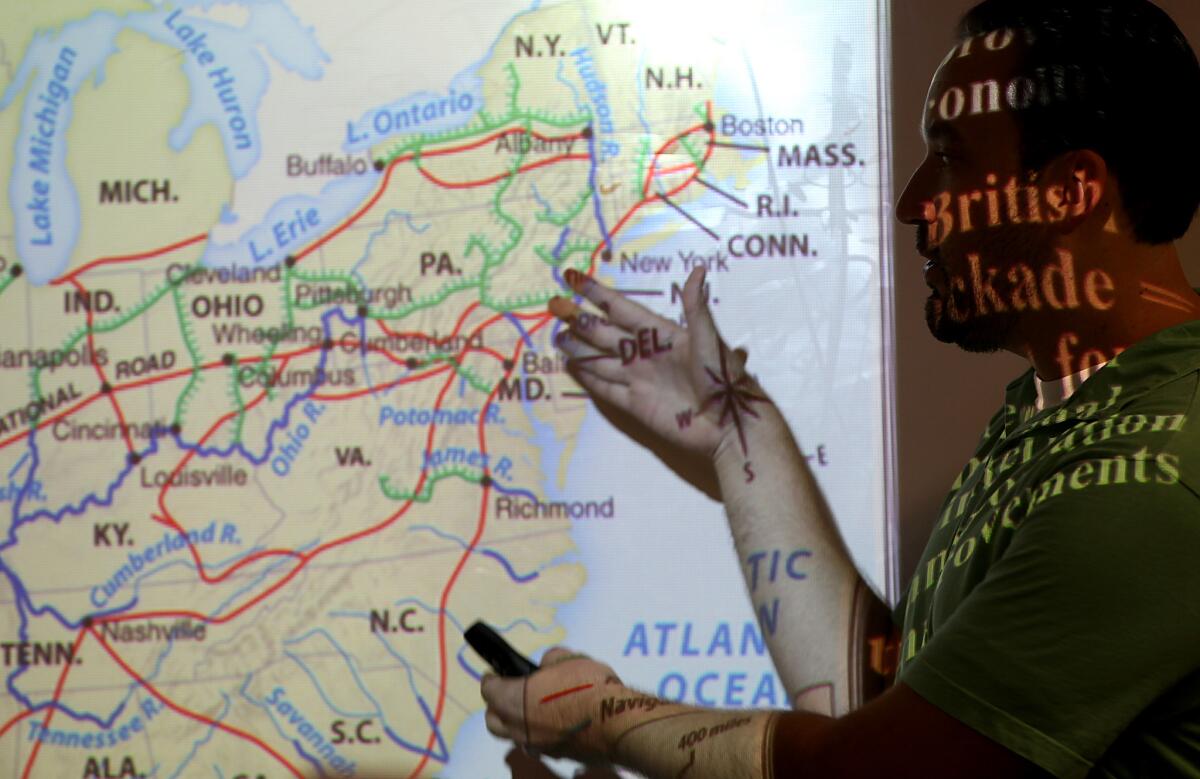

Daniel Jocz, an Advanced Placement U.S. history teacher, discusses 19th century transportation infrastructure during a 2013 class at Downtown Magnets High School in Los Angeles.

Last year, critics decried the new Advanced Placement U.S. history curriculum, saying it promoted anti-American perspectives.

This year, people on social media are up in arms about additional changes, saying the designers of the course gave in to revisionist history.

In truth, history teachers and professors said, the College Board has managed to walk a fine line in the changes it announced Thursday. They said the 2015 curriculum tells a nuanced story of American history, not “whitewashing” it nor making it all “flag waving.”

The revisions come after a year of intensive public comment, including from teachers who said the detailed framework released in August 2014 forced them to race through topics and didn’t give them the space or freedom to address key people, events or documents.

What’s new this year?

The revisions consolidate learning objectives — 19 are listed this year, down from 50 last year — and, according to the College Board, seek to make sure “statements are clearer and more historically precise, and less open to misinterpretation or perceptions of imbalance.”

They broaden how the curriculum explores American national identity and unity and how it looks at ideals of liberty, citizenship and self-governance. This includes considering American exceptionalism, which was not explicitly mentioned in last year’s curriculum — an absence that became a rallying point for conservative critics.

The new changes also highlight the nation’s founding documents and founding political leaders, including George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, John Adams, James Madison, Alexander Hamilton and Benjamin Franklin. The curriculum includes considering the productive role of free enterprise, entrepreneurship and innovation in shaping U.S. history. It explores America’s role and sacrifices during World War I and II and U.S. leadership in ending the Cold War.

Did the changes satisfy critics?

It satisfied some of the people who raised objections last year, but not all of them.

“The changes are extremely positive,” said Jeremy Stern, an independent historian and education consultant. “They have addressed what I felt were the significant problems with the first version. I have no illusions that they will satisfy people who have turned it into an ideological war, but the rational objections have been satisfied.”

Stern was a vocal critic of the 2014 framework, which he said he thought leaned ideologically to the left. He said the new version represents a much fuller vision of American history that acknowledges all perspectives. The College Board had invited him to make a detailed critique of last year’s framework as part of the public comment section, then brought him in as a consultant.

Stanley Kurtz, a senior fellow at the Ethics and Public Policy Center, a conservative think tank, was still highly critical of the framework.

“While the College Board has added a theme on American and national identity, there is little new substance to fill out the meaning of the theme,” Kurtz said in an email. “Merely referencing the words ‘American exceptionalism’ isn’t enough. The concept needs to be filled out with powerful examples.”

What is American exceptionalism?

History teachers and professors told the Los Angeles Times that American exceptionalism is too complicated and controversial a topic for the College Board to attempt to define it. By including the term as part of national identity, it give teachers the freedom to explore the topic in ways that make sense for their students.

American exceptionalism tends to have three main meanings, historians said.

There’s the conservative evangelical view, popular through the 19th century, that took exceptionalism to mean God favored the United States. Then there is the view that American exceptionalism centered on the United States’ distinctive conceptions of freedom, liberty and democratic institutions. Then there’s the view that America is exceptional in its abundant land and resources, and in its absorption of immigrants from all over the world.

Based on the learning objectives specified by the new framework, “I’m sure the College Board doesn’t mean the first, the God-centered view,” said Jon Butler, a professor emeritus at Yale University and president of the Organization of American Historians.

What do history teachers and professors think?

All the history teachers and professors interviewed by The Times said that the flap over the 2014 framework was mostly hyperbolic and that it was powered by people who had not read the curriculum. But they believed the revisions addressed some very real problems.

For instance, Butler pointed out that the 2014 version described President Reagan’s rhetoric as “bellicose.” That’s a matter of interpretation, not fact, and didn’t belong in the framework, Butler said.

The 2014 framework also did have a tendency to focus on the negative instead of the positive, historians said, and has been corrected.

Discussion of the Gilded Age in the 2014 framework, for example, focused on monopolist practices and the exploitation of labor, said Chad Hoge, an AP U.S. history teacher in Roswell, Ga. The 2015 framework adds consideration of innovations in management and industrial design.

Similarly, the 2014 framework focused almost exclusively on the plight of American Indians and not at all on the reasons American settlers were moving west, Stern said. Now both sides are considered.

Stern also said that the 2014 framework tended to judge the past by present standards, rather than by common attitudes during that time.

“Educators should seek neither to attack the past nor to glorify it (and certainly not to sanitize it) -- they should seek to explain it in as balanced, neutral and contextual a manner as possible,” he said in a follow-up email.

All of the history teachers and professors interviewed said that the new framework still rightly includes gender and race issues, and that it left a lot of room for teacher autonomy in deciding where to focus.

“It is not a prescription of the interpretation of American history, but it is a prescription for the subjects that commonly would be taught in a college-level American history course,” Butler said.

Teachers decide what to cover in their classes and which textbooks to use, although at the end of the year students take a standardized test written and scored by the College Board, the private company that puts together the framework.

What was last year’s controversy?

When last year’s framework was released, the Republican National Committee passed a resolution condemning the course, decrying it as a “radically revisionist view of American history that emphasizes negative aspects of our nation’s history while omitting or minimizing positive aspects.”

The RNC resolution urged Congress to withhold any federal funding to the College Board, the private company that designs AP curricula and the SAT and AP exams, until the course was rewritten. It called for a congressional investigation and at least a one-year delay in implementing the course so a committee of lawmakers, educators and parents could come up with a new version that would tell “the true history” of the country.

Education officials in Texas, Colorado and Tennessee had made moves to create their own curricula. Legislators in Georgia condemned the framework in a Senate resolution. Conservatives urged a focus on topics that would promote respect for authority, patriotism and “essentials and benefits of the free-enterprise system.”

Hoge, who testified against the resolution in Georgia, thinks most of the controversy stemmed from the College Board writing the framework for experts in American history, and it being read and criticized by the general public. For instance, rather than name specific Founding Fathers, as the 2015 framework now does, the 2014 framework referred vaguely to “colonial elites.”

“I know that means Benjamin Franklin and Thomas Jefferson,” Hoge said. “But others who don’t read the language that way, they may think, ‘My gosh, what have they done, they’ve taken all these great men out of history.’”

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.