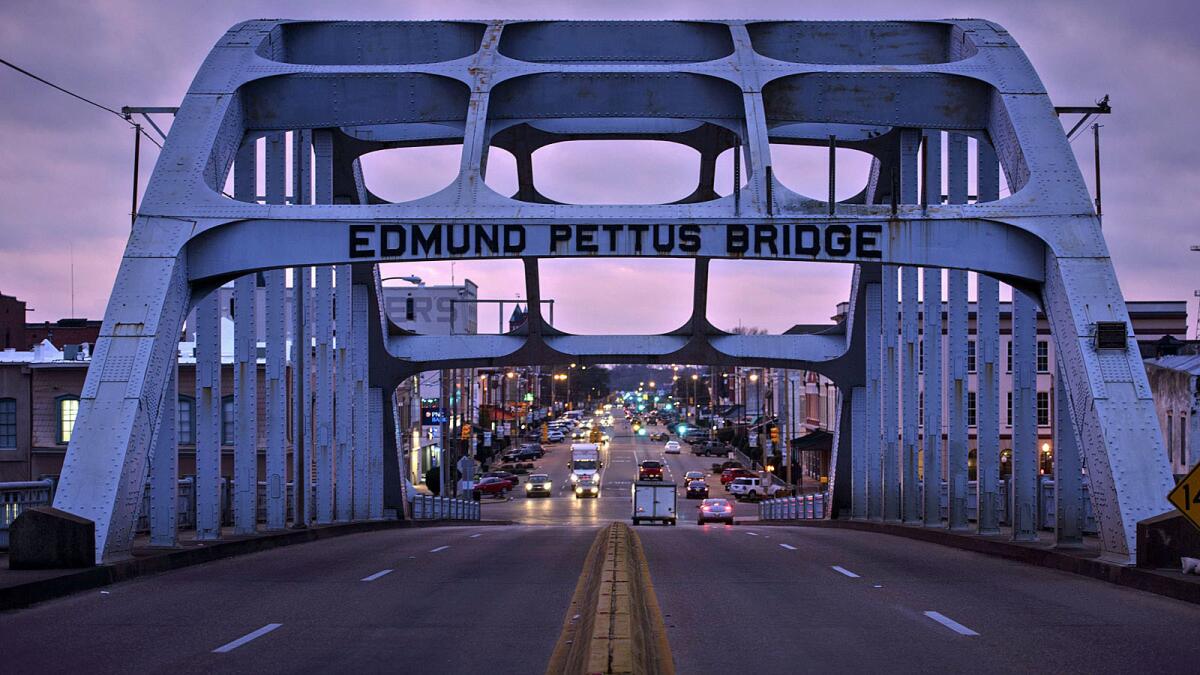

Selma updates: Recalling ‘Bloody Sunday,’ crowds cross Edmund Pettus Bridge

Crowds in Selma, Ala., marched Sunday across the Edmund Pettus Bridge, the site of the "Bloody Sunday" demonstration of March 7, 1965. Nearby, U.S. Atty. Gen. Eric H. Holder Jr., the Rev. Al Sharpton and other leaders spoke, marking the 50th anniversary of the march. The brutal police assault on civil rights demonstrators that day spurred the passage of the Voting Rights Act. Below, read Times staffers' and contributors' insights and updates from then and now.

A historic day comes to a close

Brian van der Brug / Los Angeles Times

As evening falls, there are still several hundred people making their way off the Edmund Pettus Bridge, but most of the thousands who were here today are homeward bound.

Lines of buses are in the jam of cars crowding the streets out of town. The food trucks are shutting down, though there are still lines for the Caribbean vegetarian cuisine and fried chicken.

City workers in yellow vests are clearing piles of empty food containers and plastic water bottles.

Gwendolyn Fender, 66, who came by bus from Detroit, says she's glad she got to bring her grandchildren here to the event.

“It's been phenomenal. I was able to be a part of history," she says. "I wanted to say I experienced it myself, and didn't just read about it.”

'I never became bitter or hostile, and neither can you'

Half a century ago, John Lewis was beaten senseless with a police nightstick as he tried to cross the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma.

Now a U.S. representative from Georgia, Lewis shared these thoughts Sunday:

An unusual friendship

Lloyd Gallman / Montgomery Advertiser

On May 20, 1961, John Lewis was one of the so-called Freedom Riders, testing the limits of African American access to public transportation in the South, when he and other marchers were attacked by a mob carrying rocks, bottles, even a pitchfork, as Montgomery police stood by.

In 2013, Kevin Murphy -- who was then the police chief of Montgomery, Ala. -- publicly apologized to Lewis, who is now a member of Congress, for the police inaction. Murphy had yet to be born when the attack took place, but his words were heralded as a gesture of truth and reconciliation between a white law enforcement officer and a black activist.

Murphy also gave Lewis his police badge as a way to mitigate the ugly past.

This weekend, as Lewis stepped onto the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Murphy cheered him on.

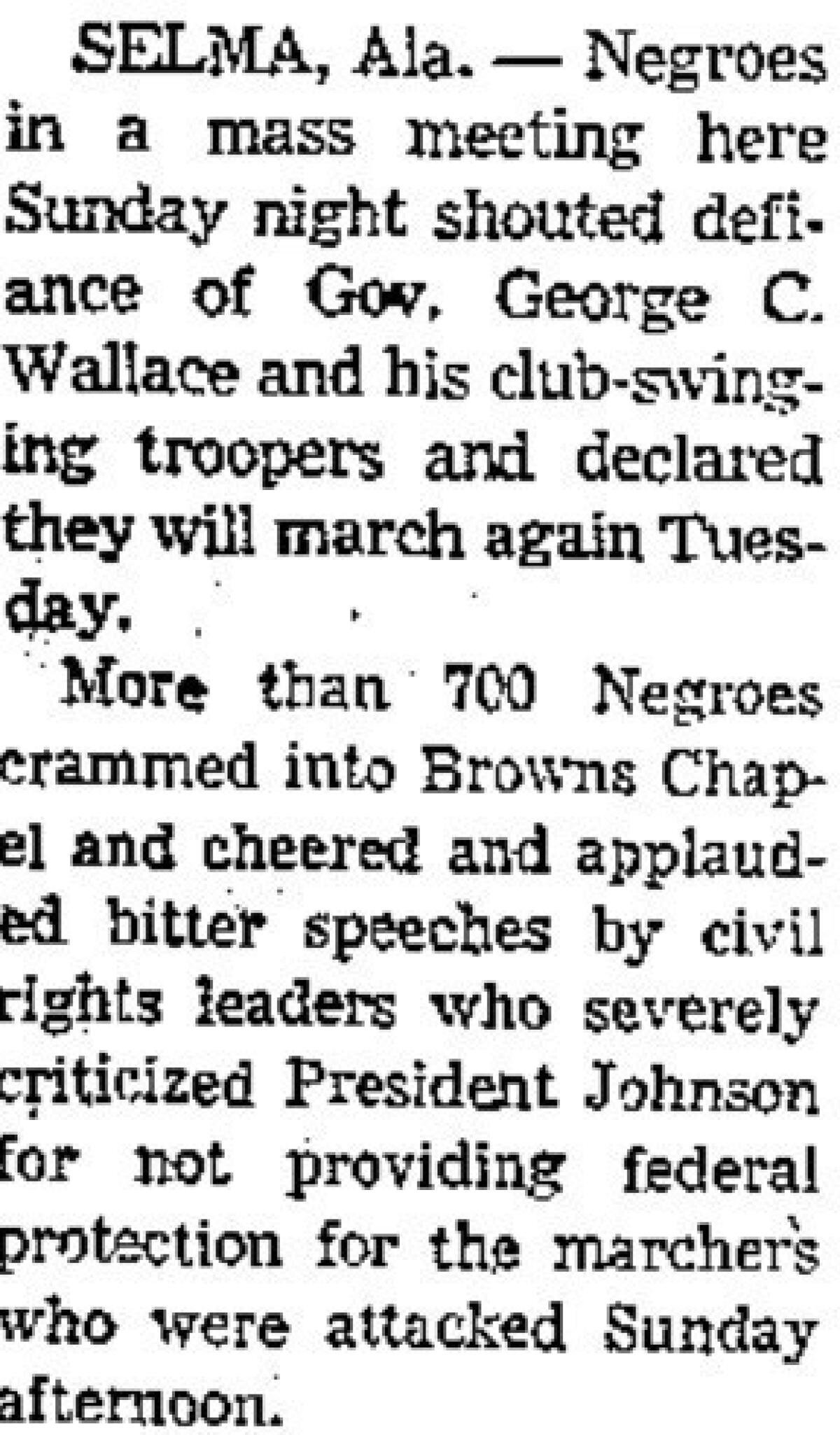

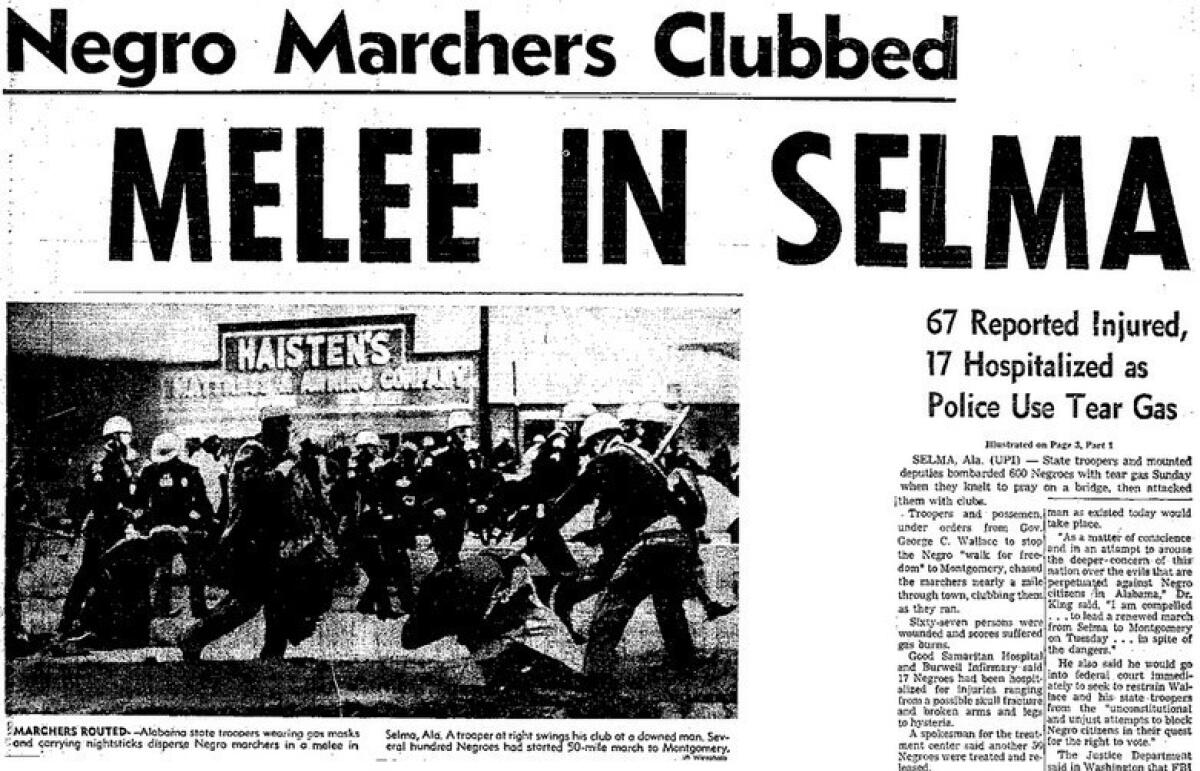

Anger at a governor, 'club-swinging troopers'

The Times' Jack Nelson, reporting from Selma, offered this scene of angry activists after "Bloody Sunday" in 1965.

Photographer captured history on 'Bloody Sunday'

James "Spider" Martin Photographic Archive

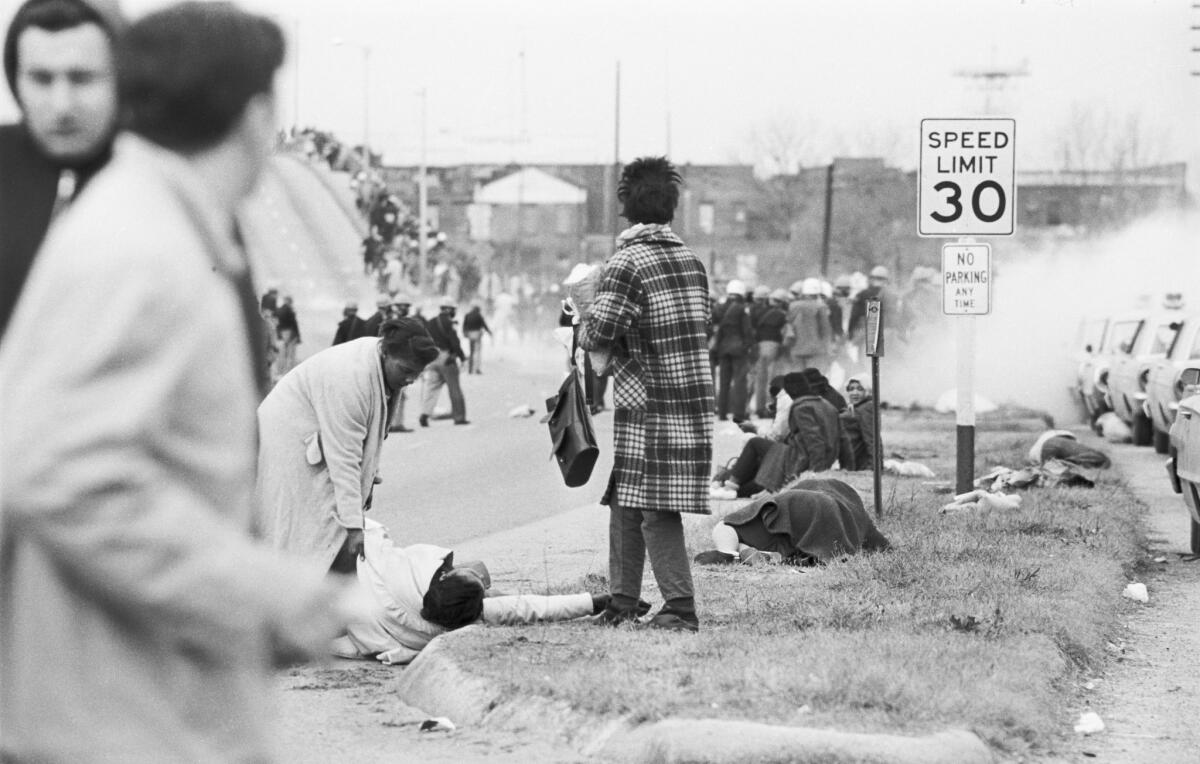

As the column of black demonstrators in Selma, Ala., marched two by two over the Edmund Pettus Bridge, James "Spider" Martin and his camera were there to record the scene.

It was March 7, 1965. Martin didn't know it yet, but he was documenting one of the most consequential moments in the history of Alabama. Every photo would become a blow against white supremacy in the South.

Martin, then a 25-year-old staff photographer for the Birmingham News, scooted ahead of the action.

Snap – The battered bodies of injured marchers litter the side of the highway as if they'd been discarded. Tear gas obscures the bridge, named for a 19th century leader of the Ku Klux Klan who was also a Confederate general.

-- Matt Pearce

Selma today

Brendan Smialowski / AFP/Getty Images

Population is about 20,000

Blacks make up 80% of the population

Median household income is $21,000

Population living below poverty line is almost 33%

Located in Dallas County, ranked poorest in Alabama

A white man of privilege: 'I'm sorry'

Ann M. Simmons/Los Angeles Times

Patrick O'Neill stood among a swarm of people on the Edmund Pettus Bridge, a sign hanging from his neck. “I'm sorry,” it read.

He wore a T-shirt bearing an image of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

When asked by a reporter why he was sorry, O'Neill said: “I thought because I'm a white guy, it might be self-explanatory.”

O'Neill, who is from North Carolina, said that on Saturday he had stood on the bridge and had a lot of conversations with African Americans. Today he wanted to return to demonstrate his support.

“I stood on the spot where people were beaten, non-violent people,” said O'Neill, 58. “I said to myself, I'm a white man of privilege in this country, and so much is still the same.”

He said that North Carolina is facing many of the same challenges as the rest of the nation, such as the disenfranchisement of black men through mass incarceration.

“I feel I need to accept responsibility for my privilege as a white male,” said O'Neill, who runs a branch of a Christian pacifist organization called Catholic Worker House in his home state.

“I didn't want to make it complicated. Just two words of repentance.”

Elvira Carter, 48, overheard O'Neill and quickly approached him: “I just want to shake your hand,” said Carter, a resident of Butler, Alabama.

“I'm here with you in solidarity, sister,” O'Neill replied.

The new civil rights leaders

Some of the concerns are old -- voting rights, police misconduct, racial profiling. Others, such as trans rights and access to technology, are more recent. Much in the spirit of activists who pushed for civil rights a half century ago, a new generation is fighting battles old and new. To catch up with these emerging leaders, including Ta-Nehisi Coates, Patrisse Cullors and Nihad Awad, click "read more," below.

-- Matt Pearce and Kurtis Lee

Singing songs of marches past

All ages and races

Bill Frakes / Associated Press

Sunday's marchers -- of all ages and races, participating individually or with their families or church and social groups -- smiled and clapped as they crossed the bridge.

There were scattered, small protests, like a group of ex-convicts who walked backward over the bridge just before the march, to protest laws that prevent felons from voting.

T.J. Blue, 78, of San Francisco walked over the bridge with her cane as children scooted around her. "I'm just glad to be here," she said.

Several helicopters and at least one drone hovered overhead, and marchers waved at them as they walked.

As if King had just stepped away for a moment

Steven Zeitchik / Los Angeles Times

A gray-green bungalow on a scraggly block in Selma was where the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. stayed during a critical period of the civil rights movement. In 1964 and 1965, he planned the march from Selma to Montgomery at the home of his friend Sullivan "Sully" Jackson, a black dentist who lived there with his family. King knew it wouldn't be safe to stay in a hotel with the political temperature rising.

In the family's breakfast nook and at a dining room table, King convened allies such as Andrew Young, John Lewis and James Bevel to talk strategy. In that dining room, the same wicker-backed chairs are still positioned around the table, as if King had just stepped away for a moment.

In one of the family bedrooms, King would pen his sermons; he'd then deliver them at nearby churches to gird congregants for the fight ahead. The bedroom's walls are painted in the same turquoise color, the bed covered in the same gold duvet -- all preserved impeccably, like nearly everything else in the house.

A scene from Selma

Ann M. Simmons / Los Angeles Times

As their parents find shade under nearby awnings, sit in chairs talking or participate in the march, a group of girls play a hand-clapping game.

'It is jam-packed downtown'

Plans to hold a formal march across the bridge appear to have gone awry, as throngs of people, overwhelming local officials, had already begun crossing the bridge.

"It is jam-packed downtown," Selma Mayor George Patrick Evans told congregants at the Brown Chapel A.M.E. Church.

The chaos meant various dignitaries didn't make it to the head of the line, but many people who had walked with the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. did make it, and led people across the bridge.

"This is no party, this is no picnic," the Rev. William Barber shouted into a bullhorn at the head of the line. "What they had was discipline. Somebody say discipline!"

"Discipline!" the crowd responded.

-- Matt Pearce and Matthew Teague ; video by Ann M. Simmons

In the path of history

Matthew Teague/Los Angeles Times

Participants sang the same songs their forebears had -- "This Little Light of Mine," "We Shall Overcome" -- and strolled by the thousands over the Edmund Pettus Bridge.

There were scattered, small protests, such as a group of ex-convicts who walked backward over the bridge just before the march, to protest laws that prevent felons from voting. Generally, though, the crowd was made up of individuals, families, church and social groups, who smiled and clapped as they crossed the bridge.

Several helicopters and at least one drone hovered overhead, and marchers waved at them as they walked.

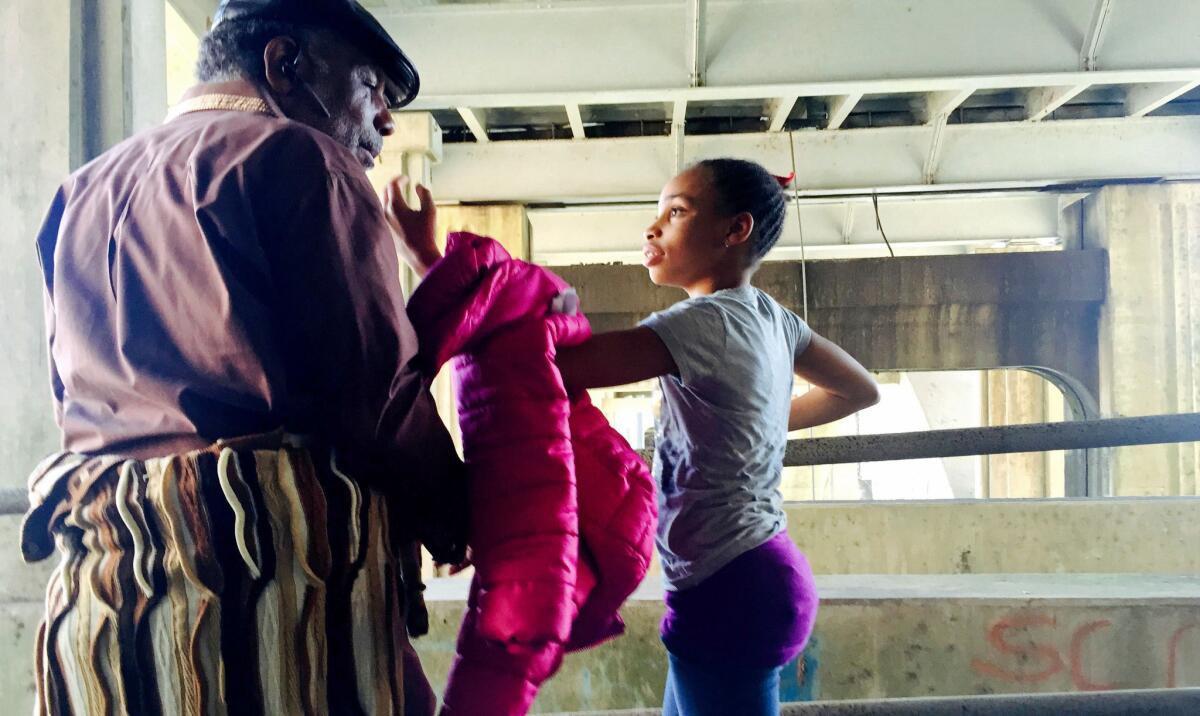

As the thousands crossed, 65-year-old Louis McCarter of Birmingham found some peace and shade under the bridge with his 10-year-old granddaughter, Chelsea. He remembered the bad times in Birmingham, he said, back when Dr. King and his supporters were at work. He brought his granddaughter to Selma to see where much of the civil rights fight began.

"Our lives are better because of this," he said.

On March 8, 1965, The L.A. Times ran this UPI wire story. The lead read: "State troopers and mounted deputies bombarded 600 Negros with tear gas Sunday when they knelt to pray on a bridge, then attacked them with clubs."

'We Shall Overcome' floats in the air

'It felt like hope magnified'

Pamela Marshall

Susan Burton of A New Way of Life in Los Angeles and Daryl Atkinson of the Southern Coalition for Social Justice finally got their turn to cross the Edmund Pettus Bridge -- twice.

Burton's dispatch:

There are just thousands and thousands and thousands of people, as far as the eye can see, people lined up coming across that bridge.

We marched backward across it the first time, signifying the rights that have been lost, the injustice of the criminal justice system. Voting rights. The fact that I can't serve on a jury, despite the fact that I'm 20 years from ever having been incarcerated.

When we reached the other side of the bridge, we turned around to march in unity with everyone else. It felt so powerful. I felt like there was a uniting of all the energy, the collective mass of individuals. It felt like we were a body, we were a power, we were a force.

There were people in wheelchairs. There was a guy who was there on the first march, he was walking up on a walker.

I'm on my way to the airport now, and people are still coming across that bridge! Oh, my goodness. It felt like hope magnified. Hope and justice magnified.

--Susan Burton

Crowd leads itself across the bridge

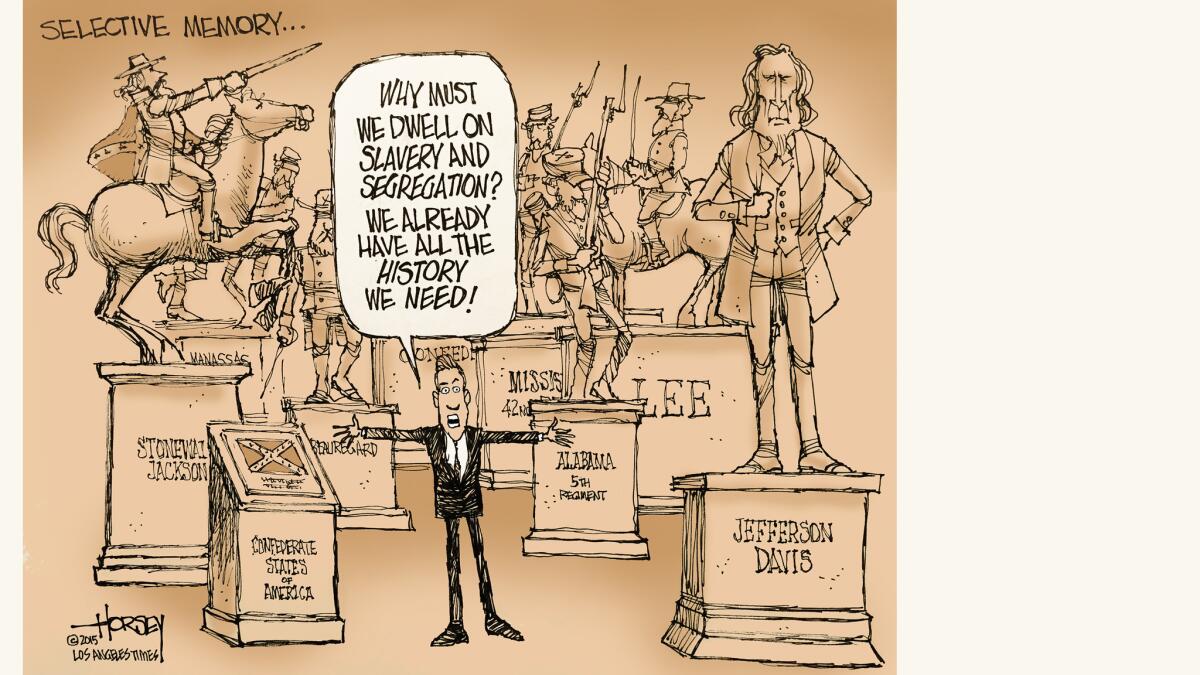

Stop the silence about the struggle

David Horsey / Los Angeles Times

Several black University of Alabama students have told me that their grandparents who lived through the dark days of segregation never talked about it, never shared their stories with their grandchildren. They had buried away the pain and shame they experienced and were not eager to dig it up again. The students also told me that the history of Alabama they were taught at school was sketchy and sanitized. Yes, they heard about Rosa Parks and Martin Luther King Jr., but not very much about the horrific social conditions that caused people such as Parks and King to stand up and say, “No more.”

Not since 1776 have there been patriots any more important to the fulfillment of the American claim of liberty and justice for all. And the fact that so many of these heroes are still alive and with us makes it crucial that we listen to their stories while they are with us.

-- David Horsey

Sharpton talks LGBT, immigrant rights

A civil rights icon is wheeled into the crowd

Ann M. Simmons / Los Angeles Times

Officer Devon Fields of the Dothan Police Department rushed to get a photo with civil rights icon Amelia Boynton Robinson, who was wheeled out into the crowd.

"It's awesome, meeting all these stars," said Fields. "It's history."

After that, 74-year-old Ed Larvadain Jr. hurried up to Fields and tapped him on the shoulder. "That woman took a whipping so you could get that job," he said.

"I know," said Fields.

Larvadain, of Alexandria, La., recalled how his wife was in labor on the day of the Bloody Sunday march in 1965.

"When she came out of delivery, she asked me, 'Did they make it?' " Larvadain said.

"I told her, no."

Read our full story about Robinson below.

Bringing the next generation

Tamara Gobi Wakhisi, 39, and her husband Kofi, 40, brought their 1-year-old daughter, Leilah, to the bridge so she could be part of history.

They had her stroller on hand.

"Just telling her she was here is one thing," Kofi Wakhisi said. "But when she sees herself being here, that's another thing."

A day for celebrating diversity

Sonya Vaughn

Marchers from the Alabama Coalition for Immigrant Justice were just one group among many that our citizen blogger Sonya Vaughn--a TV producer from the San Fernando Valley--caught with her camera today.

"Glad to see a lot of diversity in parade groups," she wrote.

Earlier, she captured one of her favorite lines from the Rev. Al Sharpton's address at the Martin Luther King Jr. Unity breakfast: "There are those that are trying to dismantle what we are celebrating," she quoted him as saying.

"We got you, Jim Crow. We'll get you, too, Jim Crow Jr."

Rep. John Lewis recalls Bloody Sunday

Saul Loeb / AFP/Getty Images

Although John Lewis has represented an Atlanta-area congressional district for nearly three decades, rural Alabama is where his roots lie.

It's where he was born and raised and where, in March 1965, he helped lead marches from Selma, Ala., to the state capital, Montgomery, in a defiant quest for African Americans to exercise the right to vote.

On March 7, 1965, the day that became known as Bloody Sunday, the 25-year-old Lewis was among dozens of black demonstrators who were tear-gassed and beaten as they crossed Selma's Edmund Pettus Bridge in what was intended as a peaceful march for civil rights.

"They started beating us with nightsticks, trampling us with horses and releasing the tear gas. I was hit in the head by a state trooper with a night stick. I lost consciousness," Lewis, shown above with President Obama, said in a "Meet the Press" interview that aired Sunday.

-- Kurtis Lee

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.