After San Bernardino attack, tech firms are urged to do more to fight terrorism

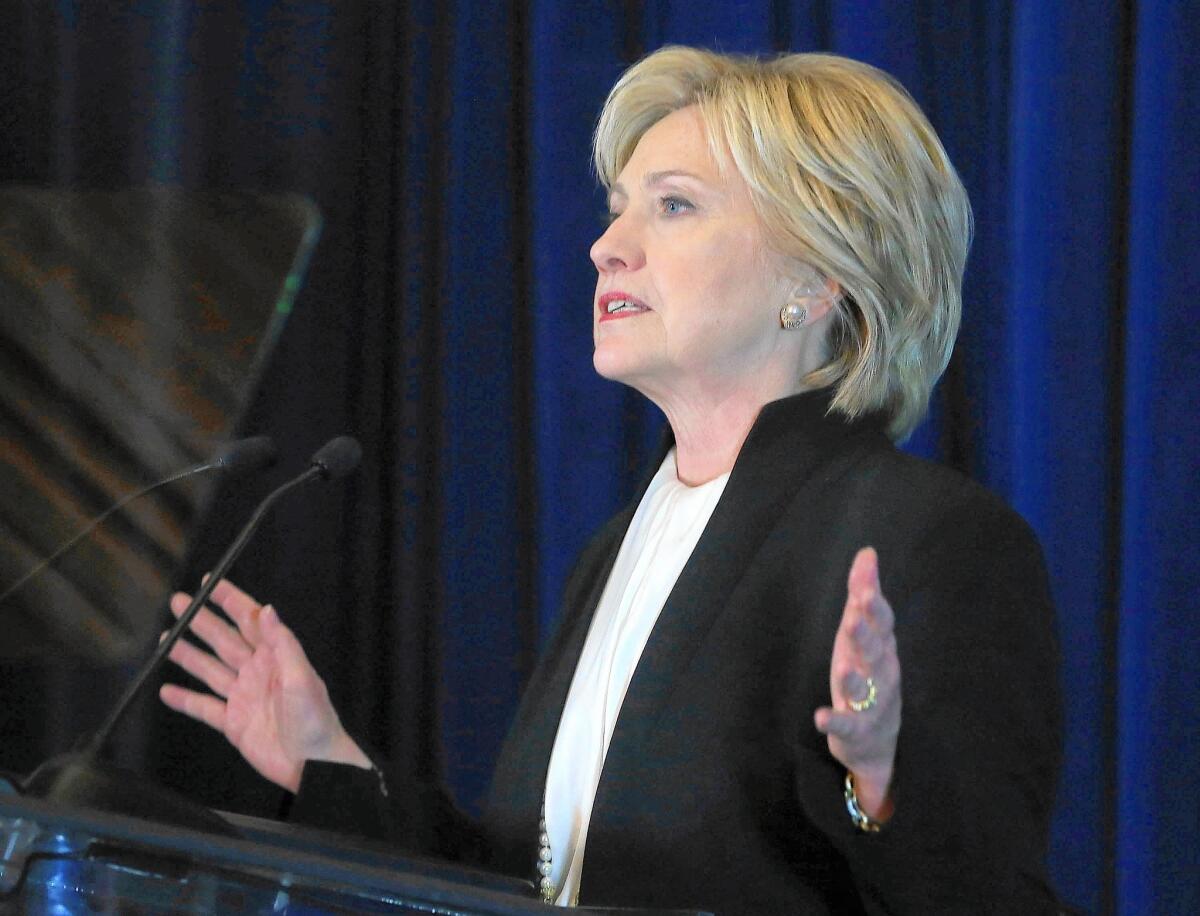

Democratic presidential candidate Hillary Clinton has called on technology companies to cooperate more with online counter-terrorism efforts and “work in disrupting ISIS.”

The attack in San Bernardino has put technology firms under new pressure to do more to fight terrorist recruitment, propaganda and plotting online, alarming Silicon Valley companies that have previously succeeded in blocking government efforts that they say would undermine privacy.

Hillary Clinton and President Obama both have publicly called on technology companies to cooperate more after last week’s shootings, saying they must work harder to help confront Islamic State, also known as ISIS, online.

Their remarks renewed the question of whether existing laws offer too much protection for Internet freedom at the expense of finding and stopping terrorists. The comments came as the directors of both the CIA and FBI were already charging that encryption services provided by some firms enable terrorists to operate out of the sight of intelligence agencies and police.

Sen. Dianne Feinstein (D-Calif.) has led a push in Congress for legislation that would require social media companies to root out and report suspicious activity. Tech firms and privacy advocates beat back an effort by Feinstein earlier this year. But the landscape has changed, and her proposal is now getting a second look.

“We’re going to have to have more support from our friends in the technology world to deny [terrorists] online space,” Clinton said in a speech here Sunday. “Technology is often called the great disrupter. We need to put the great disrupters to work in disrupting ISIS and stopping them from having this open platform for communicating with their dedicated fighters and their wannabes, like the people in San Bernardino.”

Clinton emphasized that Silicon Valley must be more engaged despite “all the usual complaints. Freedom of speech, et cetera.”

Leaders of technology firms say they have been quietly working with law enforcement in recent months to find suspicious activity on their websites and apps, remove it and report it to law enforcement. Twitter, Facebook and YouTube are constantly being scraped for suspicious content.

But the firms’ cooperation so far has not quieted complaints from law enforcement officials, nor the growing questions on Capitol Hill.

“There is a general sense that companies are not doing enough,” said James Lewis, a senior fellow at the Center for Strategic and International Studies. “That’s the problem, not that they aren’t doing anything. It’s like people woke up one day and realized ISIS had 20,000 Twitter accounts. How do you get a handle on it?”

It’s like people woke up one day and realized ISIS had 20,000 Twitter accounts. How do you get a handle on it?

— James Lewis, a senior fellow at the Center for Strategic and International Studies

The firms, wary of alienating their users, have been coy about precisely what they do and do not report to law enforcement — several declined to answer questions — but there is general agreement in Washington that the relationship between tech companies and government agencies has improved since a low point a couple of years ago, in the immediate aftermath of Edward Snowden’s disclosures of widespread government snooping on Americans’ communications.

“We share the government’s goal of keeping terrorist content off our site,” said a statement from Facebook, which is under particular scrutiny because one of the San Bernardino attackers pledged allegiance to Islamic State in a Facebook post that investigators discovered after the shootings.

“Facebook has zero tolerance for terrorists, terror propaganda, or the praising of terror activity, and we work aggressively to remove it as soon as we become aware of it,” the company said. Facebook’s policy is to alert law enforcement if the company becomes aware “of a threat of imminent harm or a planned terror attack.”

Feinstein is unimpressed. She recently recounted how she tried, without success, to get attorneys from tech companies to remove posts that provided detailed instructions on how to build bombs. Yet whether lawmakers could successfully mandate what kind of content is and is not acceptable is unclear.

“There are enormous limitations as to what you can do,” said Lorenzo Vidino, a specialist on extremism at George Washington University’s Center for Cyber & Homeland Security. Tech companies lack the manpower to monitor every posting on their sites, he said, and Congress would be hard-pressed to provide clear instruction about what material must be taken down and reported to the government.

While Feinstein and Clinton have talked about militant groups’ use of social media to recruit and inspire potential terrorists, the Obama administration seems more focused on the problem of encryption. Tech companies have fought furiously to keep lawmakers from mandating that they build a so-called back door to encryption technologies — a way for law enforcement agencies to gain access to otherwise encoded communications.

Prosecutors and intelligence officials say current technologies can make it impossible to examine suspects’ communications even if police have a valid court order.

Law enforcement officials note that some tech companies have boasted to customers that when their technologies are used, nobody can gain access to their messages ever, including the government.

The Manhattan district attorney’s office said in a report issued in November that it was unable to execute 111 search warrants for smartphones over the last year because they were running on encrypted technology offered through Apple’s iOS 8 operating system.

On Sunday, in his Oval Office speech, Obama suggested he is preparing to act on those concerns when he said, “I will urge high-tech and law enforcement leaders to make it harder for terrorists to use technology to escape from justice.”

NEWSLETTER: Get the best from our political teams delivered daily.

A senior White House official said, however, that the administration so far is not reconsidering a decision Obama made this year to avoid asking Congress to pass new legislation on encryption. Officials say they believe a legislative effort would be hopeless and are looking to forge a voluntary agreement with tech companies.

Shortly after the attacks in Paris on Nov. 13, CIA Director John Brennan warned “there are a lot of technological capabilities that are available right now that make it exceptionally difficult, both technically as well as legally, for intelligence and security services to have the insight they need” into potential attacks. “Hand-wringing” over the government’s data-collection efforts, such as those disclosed by Snowden, had left intelligence agencies without tools they need to track down terrorists online, he said.

A back door to encrypted messages is high on the law enforcement wish list. Tech companies warn that forcing them to provide one would make Internet users less safe, as such back doors could be exploited by hackers and cyberterrorists. The Internet Assn., an industry group that represents major Silicon Valley firms, argues it would be unwise to engineer vulnerabilities into technology that protects not just messages between anonymous users, but also the nation’s electricity grid and world banking systems.

But pressure on the companies is not just coming from Washington. Leaders in Europe grappling with terrorism are starting to demand American tech companies help find a solution to the encryption problem, particularly after reports that the attackers in Paris may have successfully used encryption to evade law enforcement.

“Some people seem to hope if we just sit tight the pressure will go away,” Lewis said. “But if there are more incidents, you are going to see an international debate on how to deal with encryption.”

Times staff writer Paresh Dave in Los Angeles contributed to this report.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.