VA is buried in a backlog of never-ending veterans disability appeals

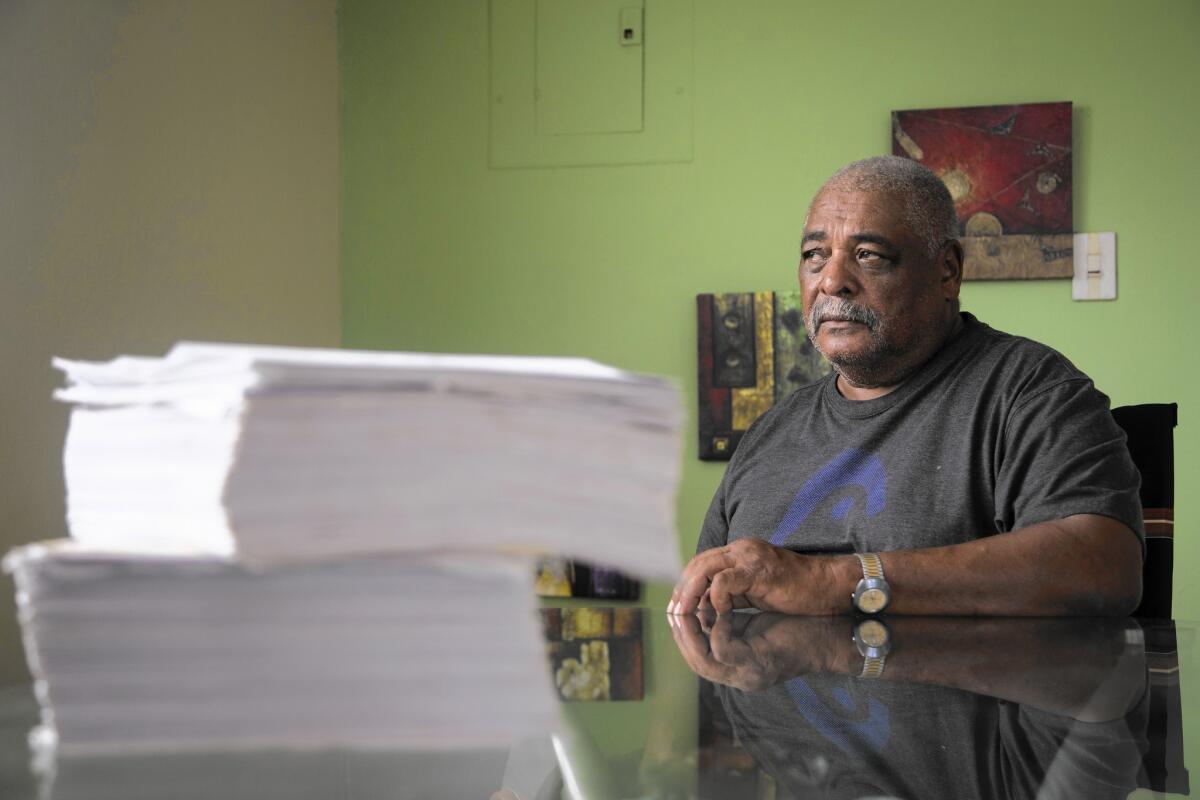

Ivan Figueroa Clausell with paperwork from his disability appeals to the Department of Veterans Affairs.

It’s a veteran disability case that never ends.

In 1985, Ivan Figueroa Clausell filed a claim for a variety of conditions he said stemmed from a car accident while training with the Puerto Rico Army National Guard. The Department of Veterans Affairs ruled that he wasn’t disabled.

He appealed and lost. He appealed again and lost again, and again and again.

In all, the VA has issued more than two dozen rulings on his case over the years. Still, he continues to appeal. Even after he won and started receiving 100% disability pay, he pressed on in hopes of receiving retroactive payments.

“I’m never going to give up,” said the 66-year-old Vietnam veteran. “I don’t care how long it takes.”

Figueroa’s is the oldest case among the more than 425,000 now swamping a veterans appeals system that advocates and government officials say is badly broken.

The appeals system does not have enough staff to handle the record number of veterans — from the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq as well as Vietnam — filing for disability payments over the last decade, then appealing when all or part of their claims are denied.

But experts point to a more fundamental problem. Unlike U.S. civil courts, the appeals system has no mechanism to prevent endless challenges. Veterans can keep their claims alive either by appealing or by restarting the process from scratch by submitting new evidence: service records, medical reports or witness statements.

They have everything to gain and little to lose by continuing to fight.

“There’s a gold ring and there’s no requirement to get in line,” said Dr. Edward Zech, a thoracic surgeon and former Navy captain who serves as the medical advisor to the Board of Veteran Appeals in Washington.

“It is intuitively obvious that there will be a backlog,” Zech said. “If we keep doing what we’re doing, we’re never going to catch up.”

Any injury or disease that can be traced back to the time of active duty — whether it occurred in combat or training or on vacation — is eligible for disability pay, with no statute of limitations on when a veteran can apply. The VA processed 1.3 million initial claims last year, a record.

The backlog has occurred as the VA has celebrated its success in whittling down delays in processing new claims. Fewer than 80,000 veterans have currently been waiting more than 125 days for initial decisions, down from a peak of more than 600,000 two years ago.

The number awaiting appeals, however, climbed from 167,412 in September 2005 to 425,480 this October.

Veterans’ advocates say the VA has simply traded one problem for another, having shifted many of the agency’s workers from appeals to initial claims.

“They’re robbing Peter to pay Paul,” said James Vale, director of benefits for Vietnam Veterans of America. “Congress doesn’t give the VA enough money to hire the staff to do the job.”

NEWSLETTER: Get the day’s top headlines from Times Editor Davan Maharaj >>

VA officials say the appeals rate has held steady for the last two decades at about 12%. The sheer number of cases, however, has become unmanageable.

Appeals that can’t be resolved at VA regional offices around the country wind up at the appeals board. The 65 judges who handle cases ruled on 55,713 cases last fiscal year — an all-time high.

They held 12,738 hearings, often by video conference. At that pace, it would take five years to see all 65,000 veterans with pending requests for a court appearance, a right guaranteed for any veteran who wants it.

While judges can grant or deny a claim, nearly half the time they do neither and instead send it back to a regional office for more thorough review.

Cases often remain in the system for years in a slow-motion volley between the appeals board and the regional offices, with occasional detours to federal court. Inside the VA, it has become known as “the churn” and “the hamster wheel.”

According to the VA, 74% of current appellants are already receiving disability pay but want the VA to recognize more of their ailments or raise their compensation for those already approved. Ultimately about 1 in 10 appeals leads to higher disability compensation.

Some veterans never get an answer. Since 2009, more than 32,000 have died with their appeals unresolved, VA data show.

Alison Hickey, who until recently was the top VA benefits official, told reporters this summer that the current procedure was “inefficient and ineffective.”

VA officials say there are two possible solutions to the bottleneck: money to hire more lawyers, judges and other staff to process appeals, or a rewrite of the law by Congress. A proposal in Congress would create a pilot program that would fast-track appeals for veterans who give up the right to add new evidence to their cases at a certain point.

“That has been incredibly controversial in the veterans’ community,” said Michael Allen, an expert on veterans benefits at Stetson University College of Law in Florida.

Above all, the disability system was designed to protect veterans from being shortchanged by the government, and veterans groups are reluctant to support changes that would limit a veteran’s ability to continue pursuing a case.

“If they limit veterans to one appeal a claim, it makes the system more efficient at the detriment of veterans’ rights,” Vale said.

Based on records collected by a congressional committee looking at the problem, Figueroa’s is the oldest pending case in the system.

He returned to Puerto Rico after Vietnam and became a police officer. In 1977, several months after joining the National Guard, he was ejected from an Army Jeep during a training exercise and broke both arms, according to extensive records he provided.

“We hit something in the road and rolled over,” he recalled.

In 1986, the VA in Puerto Rico recognized his fractures as service-related injuries but said they weren’t disabling. It rejected his claims for problems with his left hand, wrist and finger, ruling that those ailments stemmed from a mishap while changing a tire on his police car in 1980.

It also denied his claim for a “nervous condition” that emerged around the same time and led to his dismissal from the police force.

Over the next two decades, Figueroa’s dispute with the VA largely revolved around which accident — the one in 1977 or the one in 1980 — had caused the problems in his left hand. A breakthrough came in 1996. After shoulder joint replacement surgery, the VA ruled him 60% disabled. It later determined that the injury made him unemployable, entitling him to 100% disability pay.

He now receives $3,068 a month tax-free.

He has kept fighting to overturn the parts of his claim that were denied. If his other conditions are finally recognized, compensation could be backdated to when he first applied for them.

“I’ve spent a lot of time on this,” Figueroa said by telephone from his house in Cieba, a coastal town about an hour and a half east of San Juan. “But I’m not the only one.”

In 2011 — 26 years after he filed his original disability claim — the appeals board ruled that his hand injury in fact stemmed from the 1977 accident, though it was not deemed disabling enough to qualify for payment. He is still trying to get compensation for his pinkie.

More significantly, Figueroa is fighting for recognition of the “nervous condition” that was part of his original claim. He says it is really post-traumatic stress disorder linked to horrors he witnessed in Vietnam.

He was diagnosed with PTSD in 1991, when he joined the Army Reserves and was quickly deemed too troubled to serve.

The VA has repeatedly denied his claim, saying that his mental health difficulties are unrelated to his military service. The issue is under review by the appeals board.

If Figueroa succeeds, he could receive hundreds of thousands of dollars in retroactive compensation.

Twitter: @AlanZarembo

ALSO

U.S. intelligence: No specific threat to Thanksgiving travel after Paris attacks

Why fewer Mexicans are leaving their homeland for the U.S.

New York City’s schools debate removing metal detectors

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.