Newton: Nurturing hope at Homeboy Industries

Imagine Los Angeles without Homeboy Industries. Imagine that the 350 or so men and women who work at Homeboy’s various operations instead had no help finding jobs. Imagine that the 500 or so young people in the pipeline for work at Homeboy were suddenly deprived of that chance for gainful employment, security, support and stability. Imagine that the thousands of young men and women who every year have tattoos removed at Homeboy instead showed up for job interviews with necks and arms and shoulders boasting of a life they’d prefer to put behind them.

What cost would this city pay? How many of those young people would commit new crimes? Surely there would be scores more drive-bys, hundreds more assaults, many more dead and wounded. The county jails and state prisons, already full to overflowing, would be more packed. More children would grow up with parents missing or dead and all too likely to repeat generational patterns.

Life without Homeboy would be bleaker, meaner and more expensive in a society already too bleak, too mean and strapped for cash. And yet, Homeboy was almost finished a couple of years ago. Its founder, Father Gregory Boyle, had launched the organization’s expansion at its new facility on the edge of Chinatown, and Homeboy was inundated with applications and requests for help. Then the economic downturn squeezed benefactors and support fell as demand grew.

“We just weren’t prepared,” Boyle explained recently.

For a moment, it looked as though Homeboy might close. But a vigorous response from some of Los Angeles’ leading business figures helped rescue Homeboy and place it back on a path to solvency and service. (Among the most important participants was home builder Bruce Karatz, who had reason to want to restore his reputation after he was indicted — and later convicted — for back-dating stock options). Today, Homeboy raises about a third of its annual budget from its restaurant and from other sales, with philanthropy covering most of the rest of its $14-million annual budget.

That was Homeboy’s closest brush with insolvency, but the organization and its founder had weathered excruciating times before and are likely to again. Boyle refers to the years from 1988 to 1998 as the “decade of death,” when gang violence tore through the city and county. In those days, Homebody was sometimes vilified for offering help to those many saw as dangerous and undeserving. Boyle never flinched.

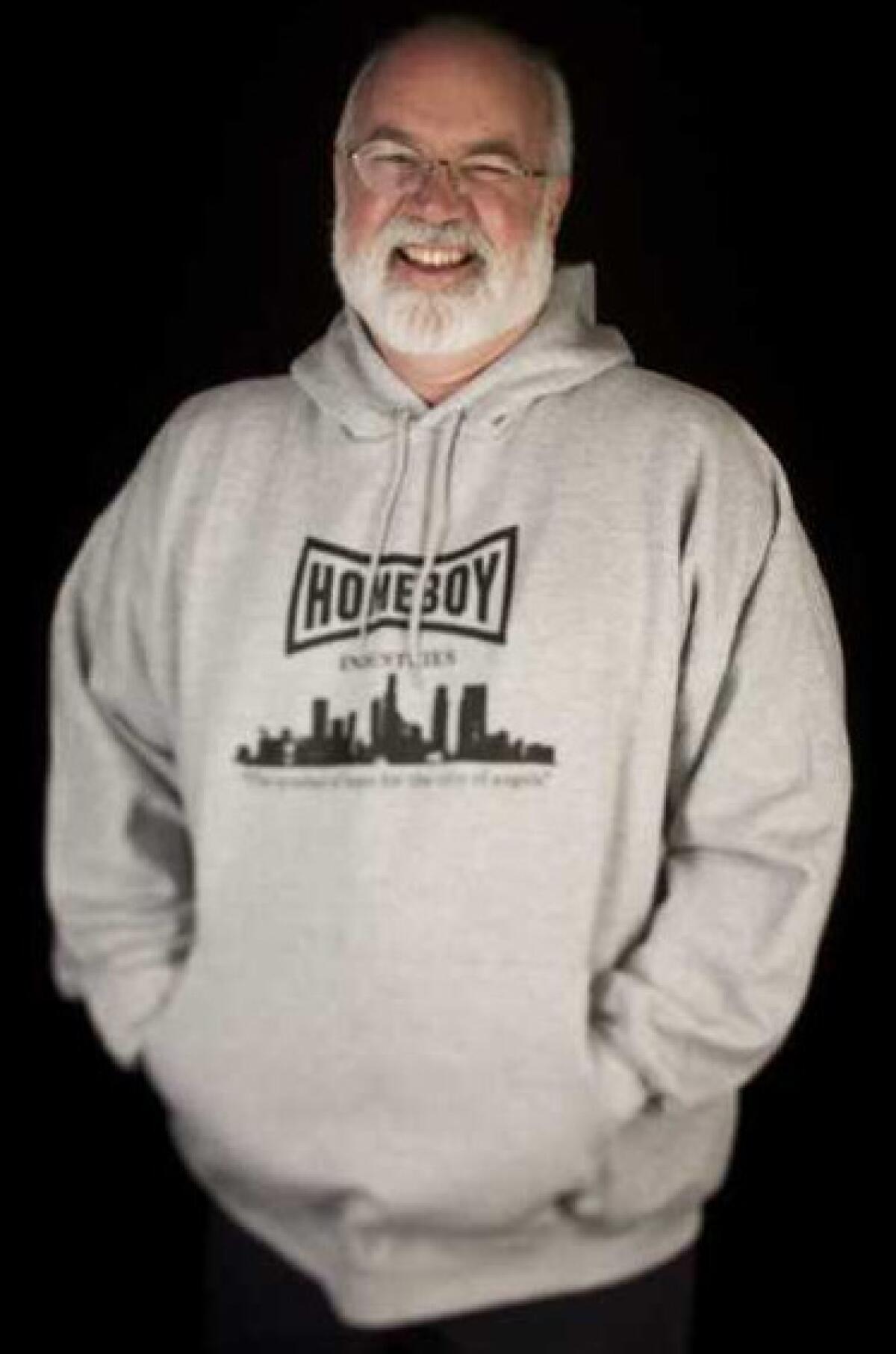

Homeboy now has become a fixture of the city, and its founder an admired icon. As we talked the other day, tours at Homeboy shuffled outside Boyle’s glass-walled office. “Viewing the founder in his natural habitat,” he said, his smile as warm as ever. In the 20 or so years I’ve known Boyle, he’s grown a little rounder and a little grayer (who hasn’t?), but that smile survives.

Homeboy — or “Hug-a-Thug” as some skeptics call it — still gets the occasional sneer, and it has had to evolve over the years. Its current challenges are different in some ways than in those years of staggering carnage. Today, Los Angeles County is home to about 300 gang homicides a year, less than a third of the annual toll in the decade of death. But in those horrible years of loss, Boyle recalls that he nevertheless could regularly find work for those who participated in Homeboy’s programs. Now, Homeboy is admired, its work appreciated, but jobs are scarce. “You want people to make the connection between public safety … and giving these people a chance,” Boyle said, and for a moment seemed discouraged.

Not for long. For Boyle, hope is the expression of compassion, of his profound belief in the human spirit. We happened to discuss the gruesome killings of Afghan civilians, allegedly by an American soldier, at a time when officials around the world were condemning the serviceman. Boyle expressed his view that only a mentally ill person could do such a thing, and that the only acceptable response to such an illness was to be compassionate for the person suffering it.

A few weeks later, while I sat in his office, Boyle glanced up, a look of alarm on his face. He excused himself and returned a few moments later, explaining that a young man outside his office had swatted his young baby. Boyle’s response was not to blame but to teach. “That’s the way he knew,” Boyle said of the young man. Now he knows better.

Boyle turns to Homeboy’s second quarter-century with some conventional aims: He’s hoping to build an endowment that would stabilize the organization’s funding. But he’s always thinking beyond those goals too. Lamenting the dearth of jobs today, he imagines a society in which employers feel an obligation to hire one additional worker as part of their social duty. “That’d be a nice little movement,” he said, and smiled.

Jim Newton’s column appears Mondays. His latest book is “Eisenhower: The White House Years.” Reach him at jim.newton@latimes.com or follow him on Twitter: @newton_jim.