Op-Ed: Remember King George III’s injustices on the first Trumpian Independence Day

In 1976, the United States’ bicentennial year, my little brothers and I woke up on the Fourth of July in a spirit of patriotic fervor so overflowing that we felt compelled to share it with the neighborhood. My brother Justin propped his stereo speakers on the ledge of his bedroom window, facing out, above the basketball backboard, and cued up a record of all-American ballads and anthems, which we blared at top volume, sending belligerent strains of music lolloping through the treetops of the maples and oaks of a dozen neighbor lawns. Among the songs were “Yankee Doodle Boy,” “You’re a Grand Old Flag,” Kate Smith’s version of “God Bless America,” and a gung-ho number whose title I never knew, but whose refrain asked, “What’s more American than saying — I am, I am, I am?”

Ours was not a fist-pumping jingoistic family; but we were history-minded, and conscious of our advantages as American citizens. Our dad had been an Eagle Scout, and our mom had an outsize sense of occasion and community outreach that meant we celebrated everything remotely celebratable. The month before, our parents, stirred by the significance of our nation’s birthday, had loaded the three of us into the station wagon, and driven us from our Indiana town to Washington, D.C., Philadelphia, and Gettysburg, Penn., so we could absorb some of our country’s most resonant national symbols — the Lincoln Memorial, the Liberty Bell, and the Civil War battlefield where, in 1863, an eloquent, unifying leader from Illinois (our parents’ home state) had declared to a doleful crowd that, despite the rancor seething among the populace, this American experiment of “government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the Earth.”

For the record:

6:12 p.m. April 23, 2024This article originally gave the year for the Gettysburg address as 1864. It was delivered in November, 1863.

Not often, but every now and then, I remember the spontaneous outpouring of love-of-country my brothers and I gave vent to on that long-ago Independence Day. One time in particular comes to mind. It was days after 9/11, in New York City; and I was walking, kind of shell-shocked, like everyone else in the city, into the Astor Place Kmart to do some errands. As I approached the entrance, I looked south down Lafayette Street and saw the still-smoldering rubble of the twin towers. (Two days earlier, on the 11th, one block away, I had watched the towers sink to the ground.) Once through the revolving doors, I was met by the voice of Kate Smith belting “God Bless America,” with strong, proud confidence, her pure, assured notes pouring through the store’s speakers, washing over the streaky linoleum, the air-conditioned aisles, and started to cry. The triumphal playlist from 1976 now seemed recast as dirge, echoes of an era of peace, plenty and optimism, retrievable now only in memory.

The abuses of George III seem less notional now, less archaic and unrepeatable than they once did.

Back in the ’70s, my whole family — parents, cousins, siblings, grandparents — lived in Illinois or Indiana. But in ensuing decades, most of us dispersed: to Oklahoma, Texas, California, Washington state, New York and Virginia. Still, every other summer, for more than 30 years, all of us have gathered for a week in northern Michigan for a Fourth of July reunion. At the gift shop of the tiny harbor village, my nephews and nieces load up on smoke bombs and sparklers and snakes, just like we did in the ’70s; and on the Fourth itself, three generations of us stake out spots along the picket-fence and flower-basket lined main street, where a parade of buntinged boats and floats passes by before lunchtime.

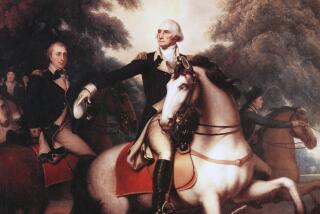

In the afternoon, after the picnic, before family fireworks on the beach (Roman candles and bottle rockets), and hours ahead of the show-stopping town display in the sky above the lake, our Aunt Ea reads aloud the Declaration of Independence, the words that the Founding Fathers signed and made public on July 4, 1776, listing the tyrannical abuses of a foreign power — England — that had spurred them to rise up in revolution. Abuses like: refusing to pass laws that help the public; refusing immigrants access to the country; and obstructing justice.

I’ll admit, in past years, I have not always listened with full attention to Aunt Ea’s recitation. My first political memory was of Watergate, in 1973 and 1974, when I was 7. Since the country had weathered that demoralizing episode well enough, it did not seem urgent to me to revisit King George III’s injustices. But this year, a fractious and controversial U.S. administration has plunged the country into a mood of division, anger and suspicion, testing the cohesion of our nation and the civility of our citizens toward each other. The abuses of George III seem less notional now, less archaic and unrepeatable than they once did. These days I’m grateful for the tradition my aunt instituted, teaching the younger generations to respect the historic roots of our national holiday.

It’s a good thing, I think, as a kid, to feel proud of your country. But the Declaration of Independence reminds us that the freedoms we enjoy are freedoms that our ancestors fought for; and freedoms that we have to defend, if we don’t want to lose them. That’s another song that was on the album Justin cued up, in that golden, liberated summer, that I want my nephews and nieces to hear and understand: “Freedom Isn’t Free.”

Liesl Schillinger is a writer, translator and author of the book “Wordbirds.”

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinion or Facebook

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.