Opinion: Taylor Swift fans stymied on Spotify but not on YouTube

Here’s another story for the People Aren’t Stupid files:

After Taylor Swift pulled her songs from Spotify (and Rdio’s free tier), ostensibly to promote sales of her new album “1989,” the popularity of Swift’s music on YouTube skyrocketed. That’s according to research Nielsen did for Mashable last week.

Mashable went on to do a back-of-the-envelope analysis comparing the royalties YouTube probably pays for streams versus what Spotify pays (the former number was based on an estimate of ad sales, the latter on what Spotify has disclosed). The conclusion was that Swift would have come out ahead had she left her tracks on Spotify, which is what I argued a few weeks ago.

Let’s be clear about one thing: Discussing the economic effects of boycotting Spotify isn’t the same as discussing whether Spotify pays people fairly, or whether artists and songwriters should be getting a bigger cut of the pie. Instead, this is about whether music fans can be prodded to spend money on a format they don’t want, whether it’s a downloadable MP3 or a plastic CD, by denying them the format they do, which is an on-demand stream.

Admittedly, the Nielsen data don’t prove that Swift’s Spotify blackout caused the rise in her popularity on YouTube, they just show a correlation between the two. It’s possible that the wall-to-wall marketing for “1989” and the release of her latest single, “Blank Space,” on Nov. 12 were entirely responsible for the surge in views of all Taylor Swift-related videos on YouTube. Heck, the media tempest generated by her Spotify boycott probably helped YouTube too.

Nevertheless, there are a couple of inescapable conclusions here.

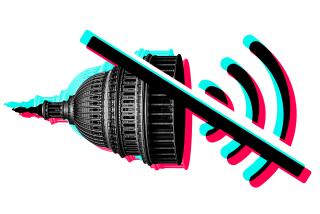

First, people who want to stream music for free will find a way to do so. Spotify isn’t really competing with music sales, it’s competing with YouTube, Pandora and the host of other streaming sites (including illegal ones). The best evidence of this is the fact that YouTube is launching its own subscription music service to try to make inroads into the market that Spotify is targeting.

Second, the heavy streaming on YouTube didn’t stop Swift’s album from selling like gangbusters. It’s impossible to tell how many people who might have bought “1989” settled instead of listening to its tracks on YouTube -- and yes, every single track is there, often accompanied by cover versions. But it’s certainly true that many, many people who’d never thought of buying Swift’s album are streaming at least some of those videos and generating revenue for Swift in the process.

The debate over which effect is bigger -- lost sales or found revenue -- is religious at this point, and it’s tied closely to the (separate) questions of whether streaming royalties are large enough and properly divided among the various interests (label, artist, songwriter, producer, manager, lawyer ...). Still, the trend lines seem clear.

Data from the Recording Industry Assn. of America show that streaming revenue grew 28% from mid-2013 to mid-2014, and it made up more than a quarter of the $3.2 billion collected in the first half of the current year -- up from one-fifth in the first half of 2013. That’s driven mainly by paid subscriptions to music services, which industry analysts say generate many times more dollars per user than streams do. The number of paid subscribers in the United States is growing rapidly too; it averaged 7.8 million in the first half of the year, compared with 5.5 million in the first half of 2013.

These data tell us that consumption habits are shifting. Diehard fans will continue to buy what their favorite artists release, but more casual ones are finding other ways to scratch the itch. You could argue that Spotify, YouTube and their ilk are enabling this shift; I think they’re just trying to capitalize on it. Those who don’t like what their getting out of this arrangement should focus on getting a bigger share of the proceeds, rather than counting on the consumption patterns of the late 1990s to magically return.

Follow Healey’s intermittent Twitter feed: @jcahealey

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.