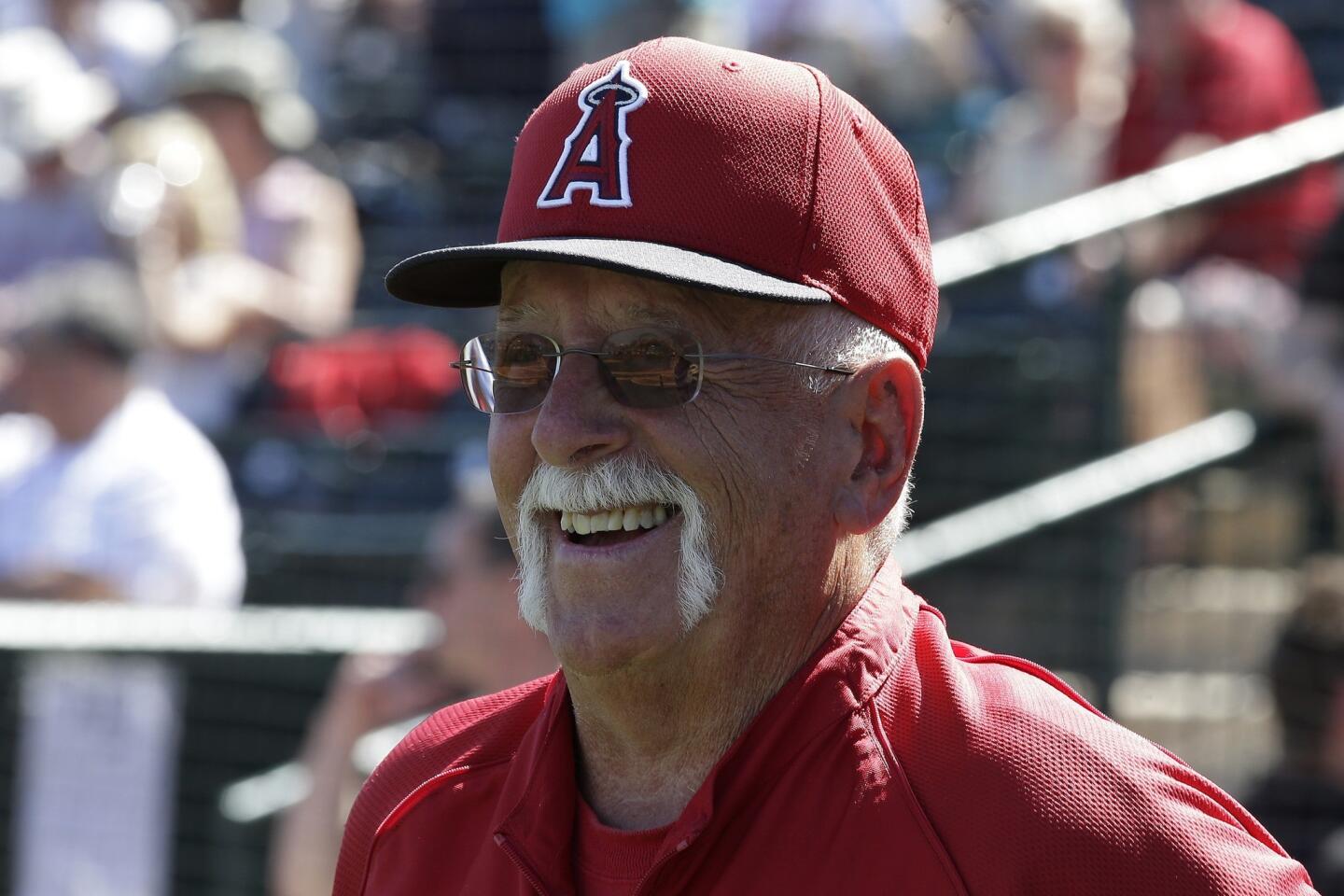

Bill Lachemann, 78, keeps Angels ahead of curve behind the plate

TEMPE, Ariz. — Bill Lachemann was on the same Dorsey High baseball team as legendary manager Sparky Anderson. He played his first professional game five years before Angels rising star Mike Trout’s father was born and caught former Angels pitcher Jim Abbott’s first bullpen session four years after qualifying for an AARP card.

He turns 79 next month, and he is 27 years older than the team that employs him, the Angels.

And what he does now is what he’s been doing for decades: produce major league ballplayers.

Lachemann coaches the Angels’ catchers during spring training, then travels the country during the summer to work with raw minor leaguers in places like Orem, Utah, Burlington, Iowa, and San Bernardino.

“It’s not a job, it’s a fun thing for me,” Lachemann says. “Whatever they want me to do, they just point me in a direction and I do it.”

By his own count, 50 of the 190 catchers he has tutored have made it to the majors.

Each morning, he pulls on a red Angels warmup jacket and bright white uniform pants, then ambles across the locker room to exchange pleasantries with the young men he works with.

“He’s the first one in here . . . has his shin guards on before a lot of these guys are even out of bed,” says Angels Manager Mike Scioscia, a two-time All-Star catcher with the Dodgers during his playing career.

The shin guards are something of a trademark.

Lachemann wears them mostly out of habit these days, but until he had a heart attack three years ago he frequently would catch and throw batting practice. Now, after six decades of wearing them to work, Lachemann walks stooped and with a slightly bowlegged gait. That is his only concession to age.

In the clubhouse, the players follow a strict code: high-priced veterans dress on one side, the pitchers line up side-by-side in the far corner, and across from them in the corner nearest the exit are the seven catchers who have been called to camp.

The five pounds of extra gear those catchers wear on the field spills from red and blue duffel bags — chest protectors, shin guards, hard plastic skull caps and steel-and-Titanium masks.

The equipment used to be called the “tools of ignorance,” suggesting that anyone willing to squat behind the plate, inches from a man wielding a wooden club, and trying to stop a ball darting in different directions at nearly 100 mph had to be a little crazy. But Lachemann, a former Marine with a degree in education, is far from ignorant — especially when it comes to catching.

After leaving the clubhouse on a bright March morning, he jumps in a small white golf cart and heads to the most distant back field in the Angels’ sprawling complex. There, he shares his wisdom with prospects like Jett Bandy, a 22-year-old from West Hills, and Carlos Ramirez, a 25-year-old from Arizona.

As Ramirez crouches behind the plate, Lachemann stands to one side, leaning on a fungo bat. “I mostly observe,” he says.

When the bullpen session ends, Lachemann shuffles over and offers a critique. His words are firm but he doesn’t scold. Ramirez, who is bathed in sweat, listens intently.

“Don’t get lazy with your glove. Make sure your setups are all right,” Lachemann says, referring to how the catcher positions his hands and body to receive each pitch. “And watch your footwork.”

He then bids Ramirez good day, climbs into his golf cart and heads back to the clubhouse. He’s happy, because Ramirez is working hard and improving rapidly.

With the major leaguers, most of Lachemann’s work takes place out of public view, in the dugout or a room where he pores over video in search of minute mechanical flaws. During games, he charts each pitch, then uses the information to quiz the catchers a few innings later, asking them to recite every pitch that was thrown.

It’s a test to see if the catchers are paying attention, and to help them detect patterns that might allow opposing batters to figure out a pitcher’s strategy.

Hank Conger, an Angels backup and a former first-round draft pick out of Huntington Beach High, says he used to fret about those question-and-answer sessions, but concedes they “made me a lot better.”

“The input that he gives us, the feedback that comes from his experience and what he’s seen, it’s been real helpful.” Conger says.

Conger is grateful for Lachemann’s advice, but he can’t help but tease the coach about being old school. With a bushy white mustache, gray hair and wire-rim glasses, Lachemann looks more like an Old West sheriff than a modern-day baseball coach.

His brothers, Marcel and Rene, both managed in the major leagues, Marcel with the Angels in 1994, ’95 and ’96. He and Rene also briefly played in the majors, but Bill never made it out of the low minors during a six-year playing career.

Asked why, Lachemann is blunt. “Speed,” he says. “I can run as fast now as when I was playing.”

Lachemann’s first professional contract, signed in 1955, brought him a salary of $150 a month. He figures the closest he got to the big leagues was a 1959 spring training at-bat, when Dodgers Manager Walter Alston sent him up to pinch-hit for Don Drysdale.

“I went up there and took the first pitch for a strike,” Lachemann recalls. “Second pitch, I looked at it. Another strike. And I said, ‘Screw it, I’m going to cut from my rear end.’ I struck out. And when I sat down my legs would not quit shaking. I was so nervous.

“That was my only chance. If I would have gotten a base hit, who knows what would have happened.”

That failure would lead to success for dozens of young catchers who later came through the Angels and San Francisco Giants organizations. Lachemann coached and managed nine years in the Giants’ minor league system before joining the Angels.

“He’s got just a great understanding of where guys should be and what they need to do to function on the field,” Scioscia says. “He’s a great evaluator, especially on the mental side. He puts a lot time into that. He’s just a terrific mentor to these kids.”

Asked for his take on the best player he’s seen over the years, Lachemann doesn’t hesitate.

“If you can’t say that Mike Trout is the best, then you’ve got a problem,” he says, nodding across the clubhouse to Trout’s locker. “The guys that can run are the guys that really impress me a lot. Because I couldn’t run a lick.”

Trout stole 49 bases last season, when he was American League rookie of the year and runner-up in the most-valuable-player voting.

A lifetime of squatting has cost Lachemann one knee, which was replaced last fall. He will have the other replaced in October. In addition to the heart attack, Lachemann in recent years has battled colon cancer and diabetes.

He also lost Darriel, his wife of 52 years, who died of cancer last year on Mother’s Day at the age of 70.

Baseball had taken them both to more small towns and greasy-spoon diners than any couple should have to endure. “She was always with me,” Lachemann says.

He has three grown children, a daughter and two sons, and holds close the game that has been his life’s devotion.

“When I die, I want to die on a baseball field,” he says.

Oh, and if it’s not too much trouble, he adds with a twinkle in his eye, he hopes those shin guards are on when he’s buried.

Twitter: @kbaxter11

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.