Tony La Russa sticks out his neck in trying to make the Diamondbacks winners

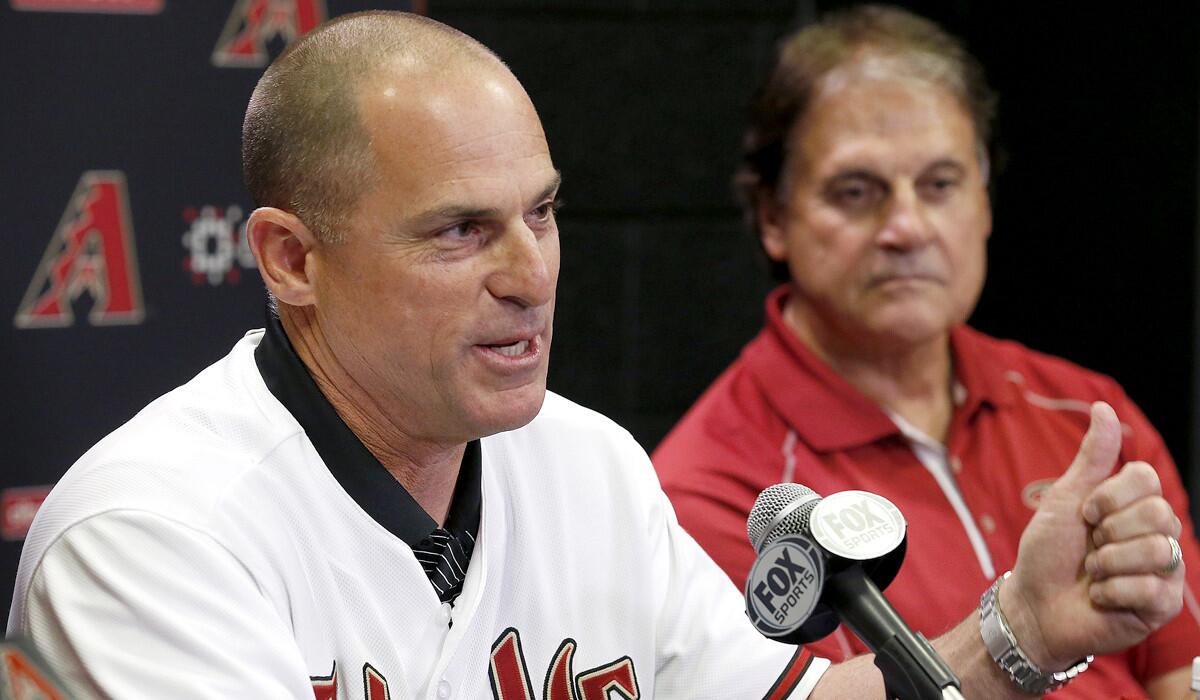

Chip Hale, alongside Chief Baseball Officer Tony La Russa, fields questions from the media as he’s introduced as the manager of the Arizona Diamondbacks on Oct. 13, 2014.

In one of the more curious developments in the major leagues this spring, Tony La Russa is now considered an idiot.

This is the same La Russa who has a law degree, who won more games as a manager than all but two men in major league history, who was unanimously elected into the Hall of Fame in his first year of eligibility.

“I’ve been a guy in uniform. What do I know about the front office?” La Russa said, sitting in a second-floor office, his briefcase beside him. “That’s definitely a fair criticism.”

La Russa is 71. He is in the third year of a desk job, as chief baseball officer of the Arizona Diamondbacks. He invented the modern bullpen, with all its roles and specialists. He played platoon splits 30 years ago, trying to gain a competitive advantage by ordering his team not to publicize his hitters’ batting average splits against left-handers and right-handers.

“I did work 30 years for three great owners and front offices,” he said. “I think I paid attention.”

In hiring his general manager, La Russa bypassed what he branded the increasingly common “Harvard, well-educated numbers guy” in favor of one of his former pitchers, Dave Stewart, who had two decades of experience as an agent, coach and front-office executive.

The Diamondbacks made two major off-season moves, and national analysts fitted them for dunce caps. They lured pitcher Zack Greinke for $206.5 million, awarding him the highest average annual salary in baseball history and committing him to their small-revenue team through age 37. Then they spent dearly to acquire pitcher Shelby Miller, trading away a package featuring outfielder Ender Inciarte and infielder Dansby Swanson, the first overall pick in last year’s draft.

The Dodgers could have comfortably afforded to keep Greinke but decided the risk exceeded the reward. The Dodgers hoard their best prospects rather than trade them. In this era, both of the Dodgers’ decisions fit the general framework of analytic orthodoxy.

And the Diamondbacks’ decisions?

“If we did something that sounded different,” La Russa said, “it’s not different because we know what we’re doing. It’s different because we don’t.

“I have a big objection to that.”

What the Diamondbacks are doing is the essence of “Moneyball:” zigging when the rest of the industry zags. What the Diamondbacks are doing is putting the chance to win above financial flexibility and years of player control and risk diversification, all the analytical tenets used in shaming Arizona for the Greinke signing and Miller trade.

How has the pendulum of baseball analysis swung so far that the Diamondbacks are ripped for trying to win now?

“I think there is an underlying issue,” La Russa said. “There is a perception that, if you’re not hiring [as general managers and assistant general managers] … if they’re not primarily educated at some accredited school so they can understand how much the game has improved once you break it down into metrics, then you’re going in the wrong direction.

“And I can’t disagree more.”

Diamondbacks starting pitcher Zack Greinke throws a pitch during the second inning of a spring training game against the Oakland Athletics on March 4.

The Diamondbacks have a vibrant analytics department, La Russa said, just as two analytics staffers walk past his office door. He said the Diamondbacks “embrace the metrics” and use them in balancing two kinds of analytics.

“The metrics help you analyze and prepare,” La Russa said. “Head, heart, guts. How do you measure that? Observation.

“We call it observational analytics. We put the two together.”

Every team does, in its own blend. La Russa, who made his name in the dugout, reserves a special heaping of scorn for the analytics-minded executives who devise game strategy in the front office and pass it down to the manager.

“We want our manager and our coaches down there reading the moment and making adjustments,” he said. “The idea that you can send a lineup down, that you can send strategy down — these are situations when you can’t run and can’t bunt — if people have that opinion, they are welcome to it, but the game is too dynamic.”

The Diamondbacks scoff at the analytics-based projections that see them as no better this year than the 79-83 club last year, given the additions of Greinke, Miller, infielder Jean Segura and setup man Tyler Clippard, with Inciarte as the only significant loss from the major league roster.

Arizona scored more runs last season than any National League team that does not call Coors Field home. None of the starting position players is older than 28. None of the starting pitchers is either, aside from Greinke.

After the trades for Miller and Segura, and the cash-saving trade of first-round draft pick and pitching prospect Touki Toussaint, Baseball America dropped its ranking of the Arizona farm system from sixth last year to 22nd this year.

La Russa said the Diamondbacks traded from depth in the outfield and in the middle infield to get Miller while retaining quantity and quality in its minor league system. He also said Toussaint, 19, might not have developed until the Diamondbacks’ window to win had closed.

“I would not be part of an effort where you go all in for a year or two,” La Russa said. “You get your fans excited, and then you go from the castle to the [outhouse].

“We’re all in for ‘16, because this is the year we’re playing. We believe our window of opportunity is the next four to five years.”

Said Greinke: “It’s easily a three-year base. With luck and the right moves, it’ll be able to last longer.”

Greinke is well aware of how deep the Dodgers farm system is, how the Dodgers have the resources to frustrate his Arizona timetable.

“If L.A. goes out and trades for Sonny Gray and Nolan Arenado, it’ll be a little tougher,” Greinke said.

First baseman Paul Goldschmidt, who finished second to Andrew McCutchen for the 2013 NL most-valuable-player award and second to Bryce Harper last year, leads a group of Arizona position players that Greinke calls “maybe as good as anyone’s in baseball.”

“Take offense and defense, it might be the most talented group there is,” Greinke said.

Still, Greinke is not sleeping on the Dodgers.

“Their depth is pretty amazing,” he said, “maybe the best of all time.”

The Diamondbacks weakened their depth, by a little or by a lot, with the Miller trade. Greinke was said by friends to be frustrated and disappointed at how much talent the Diamondbacks lost in getting Miller. Greinke, asked whether he liked the trade, deflected the question without a yes or no.

“You can see how many actual good players are still here,” he said. “It doesn’t help if you have 40 good players. You can only play eight good players at a time.”

Greinke is scheduled to account for one-third of the Diamondbacks’ $100-million payroll this season. He’ll be paid $34 million, with no one else on the team receiving even one-fourth as much. Miller, the next highest-paid among the starters, will be get $4.35 million.

So Greinke is relatively affordable this year, in the context of an otherwise young roster and his agreement to defer $10 million of his salary. He deferred $62.5 million over the life of the contract, but the raises for Goldschmidt, Miller and other key players over that time should rise beyond the amount of Greinke’s deferrals.

Diamondbacks President Derrick Hall said he is thrilled to have Greinke but not particularly comfortable with the deal.

“I don’t think you’re ever comfortable,” Hall said. “In a market like ours, we can’t make a mistake. We just can’t.

“We decided to take a big chance and a big risk.”

The standings are at stake, but so too is the reputation of La Russa.

He had a cushy job in the commissioner’s office, but he itched for competition rather than neutrality. He would have been running the Dodgers’ baseball operations department now had Steven Cohen been the winner rather than the runner-up in bidding for the team in 2012, when Frank McCourt sold to Guggenheim Baseball.

So here he is, trying to beat the mighty Dodgers with less than half the payroll, trying to persuade critics that his baseball smarts are not limited to managing.

“I don’t begrudge them,” La Russa said. “You’ve got to earn the benefit of the doubt, and I certainly haven’t earned it sitting in an office rather than sitting in a dugout.”

More to Read

Get our high school sports newsletter

Prep Rally is devoted to the SoCal high school sports experience, bringing you scores, stories and a behind-the-scenes look at what makes prep sports so popular.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.