Column: You might see Vista Murrieta High’s Michael Norman at this summer’s Olympics. Here’s why

Vista Murrieta senior prepares for final prep races

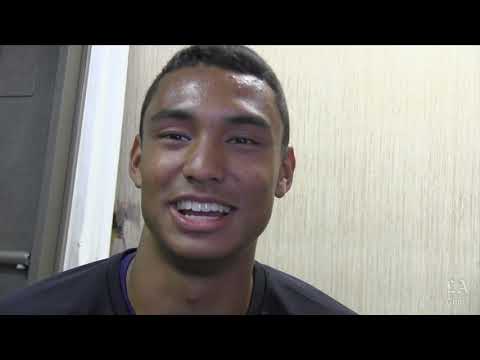

It’s midafternoon and more than 220 track athletes dressed in identical blue sweat outfits are preparing to work out at the Vista Murrieta High football field. Somewhere in the crowd is Michael Norman, the nation’s No. 1 high school track athlete, but without the trademark white headband he wears during races, he’s anonymous among the dozens of teenagers chatting and socializing.

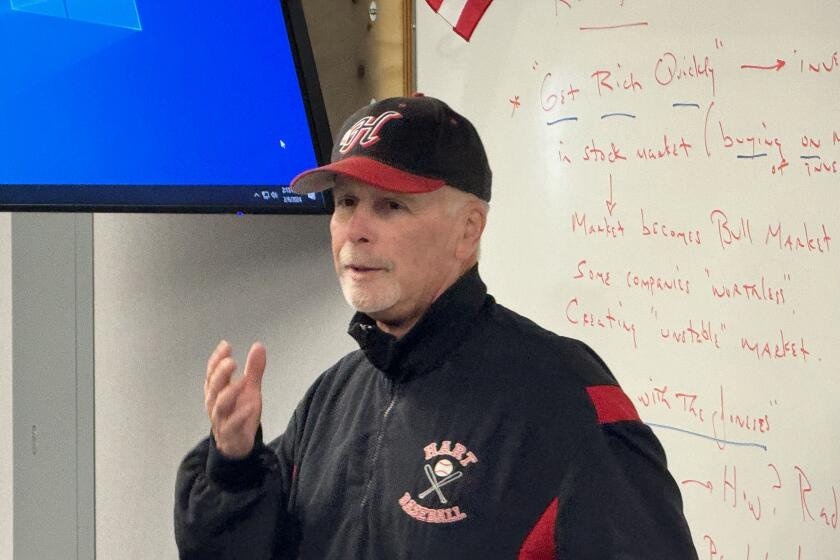

“Just another kid on the track team,” Coach Coley Candaele calls him.

Everything changes when the tall, slender 18-year-old with the effervescent smile puts on his bright orange Asics sprint shoes and starts warming up on the polyurethane track.

The reigning Gatorade national runner of the year is headed into his final weeks as a high school competitor before making a run at qualifying for a spot on the U.S. Olympic team for this summer’s Games in Rio de Janeiro.

The jump from high school directly to the Olympics is rarely accomplished in United States track and field, but Norman can’t be counted out. He enters Saturday’s Southern Section finals at Cerritos College with the state’s fastest times in the 100- (10.27 seconds), 200- (20.51) and 400-meter races (45.51). He won state titles as a junior in the 400 in 45.19 and the 200 in 20.30, both state records. Both times made him eligible to compete at the Olympic trials this summer in Oregon.

He’s like the Kobe Bryant of track and field. He’s a kid who loves his sport.

— Quincy Watts, sprint coach

To put Norman’s accomplishments in perspective, consider this: When he runs for USC next season, his sprint coach will be Quincy Watts, who set a City Section record in the 100 for Woodland Hills Taft in 1987 at 10.36 seconds and won a state title in the 200 in 20.99.

For the record: An earlier version of this column said that Michael Norman set a state record in the 200-meter dash last year at the state meet. He set state records in the 200- and 400-meter races last year at the state meet.

Norman has already bested those times, and Watts went on to win the 1992 Olympics gold medal in the 400 in 43.50.

“He has that great luxury that he can rely on his speed at any time during a race,” Watts says. “He’s like the Kobe Bryant of track and field. He’s a kid who loves his sport.”

The 400, Norman’s specialty, is a grueling race because it requires sustained sprinting from beginning to end. Norman’s combination of speed and endurance gives him options on race strategy.

Last April, in winning the Arcadia Invitational, he didn’t do anything special at the start as he broke from the blocks in a steady, sturdy stride. He gauged his competition down the backstretch, maintaining his speed and momentum. Then he unleashed a burst of speed and power around the final turn, his arms churning furiously but his stride long and smooth as he pulled away down the final straightaway.

“Michael is the perfect storm in terms of being an athlete and being a competitor,” Candaele says. “Here you have a kid that’s unbelievably gifted in terms of talent, but equal of that he has a work ethic that matches his talent.”

Candaele recently stepped down as Vista Murrieta’s football coach, having led the Broncos to seven consecutive Southern Section championship games. But he never coaxed Norman into putting on pads.

Until recently, Norman wasn’t built for heavy contact anyway. He was 5 feet 4, 100 pounds in junior high, so playing football was never a consideration. “I didn’t want him to get hurt,” says his father, also Michael. Even as a high school freshman, Norman was just 5-8, 120 pounds. Now he’s a sleek, sinewy 6-1, 170.

Norman may have inherited his running ability from his mother, Nobue, who ran track in Japan. He started running when he was in sixth grade, accompanying his older sister, Michelle, who went on to become a Southern Section champion in the long jump for Vista Murrieta in 2014 and competes for UC Irvine.

At school, Norman is about as humble as a star athlete can be. Classmates rave about how friendly and approachable he is on campus.

“I just don’t want to get a big head and see my performance go down because that would mentally mess me up,” he says.

He blushes after his races when strangers or competitors ask to take a selfie with him or seek an autograph.

“I just ran in a high school track meet, I don’t feel I’m big,” he says. “If people want to take pictures, it’s pretty cool. It’s something I’m definitely not used to. I don’t think I’ll ever get used to it. It’s a weird feeling. I’m like, autograph? I sign my name, ‘Here you go.’”

Candaele has been Norman’s coach for four years and they have complete trust in each other.

“I learned to listen to Michael’s body,” Candaele says. “He’s the motor. I just make sure that progression is there and he doesn’t race too fast too early and knows when he should run hard and when to let go.”

Norman’s success has many people excited for what the future might bring. He has a blackboard at home where he lists goals and times he wants to reach. One goal is to make the Olympic team. The trials begin July 1 in Oregon.

“I’m just going to go out there and see what I can do,” he says. “I don’t have any expectations. It’s for the experience. If I make the team, that’s a great thing. If I don’t, oh well. It’s not my time.”

For high school track fans who have never seen Norman run, there are three final opportunities — Saturday, then May 27 in the Masters Meet at Cerritos College and June 3-4 at the state championships in Clovis.

Whatever happens, Norman has left his mark.

“His range of speed and endurance,” Candaele says, “is unheard of in California history.”

Follow @LATSondheimer on Twitter

More to Read

Get our high school sports newsletter

Prep Rally is devoted to the SoCal high school sports experience, bringing you scores, stories and a behind-the-scenes look at what makes prep sports so popular.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.