Op-Ed: Vision of a great Olympian and person

I was breathless when Olympic bobsled driver Steven Holcomb’s agent called me last May to share the tragic news of his passing. Steven was a great man, a gifted athlete, and a close friend, and it’s still hard for me to accept that he’s gone. While he may not be physically with us, I can assure you his legacy, on and off the ice, will endure.

Steven helped put U.S. bobsledding back on the world map. Before his 2010 Olympic victory, America’s bobsled program hadn’t won gold since 1948, back when Harry Truman was president. Steven showed what the U.S. is capable of in sliding sports.

And what a racer he was. The most celebrated bobsled driver in U.S. history, he won a gold medal in the Vancouver Olympics, two silvers in the Sochi Olympics (recently upgraded from bronze following Russia’s doping scandal), and too many world cups and world championships to count. A kind and dedicated athlete, he’s an inspiration to our team in PyeongChang, where he would’ve raced, and without question, he’ll continue to inspire generations of bobsledders to come.

I met Steven not on the ice, but in a medical office. It was back in 2007. Steven suffered from an eye disease called Keratoconus where the cornea (outer lens of the eye) bulges out, causing distortions in vision. As the track got blurrier and blurrier on him, Steven kept the disease a secret, racing by feel. He was determined to compete in the upcoming Vancouver Olympics and win gold, his lifelong dream. Eventually, however, his failing vision became impossible to hide, and Steven could no longer race. Steven consulted with twelve eye doctors, all of whom said a cornea transplant—which has a long recovery time and meant he’d have to sit out the Olympics—was the only option. As he later recounted in his book, But Now I See – My Journey from Blindness to Olympic Gold, Steven fell into a deep depression.

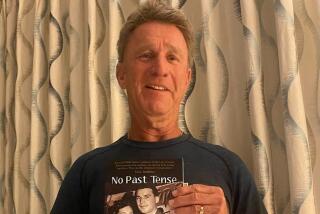

I’m an eye surgeon. In 2003, I developed a non-invasive treatment for Keratoconus—C3-R cornea crosslinking—which involves strengthening the cornea with a special application of vitamins and light. Steven, due to his bad luck with doctors, was wary on our first meeting, but courageously, he eventually agreed to undergo the relatively new procedure at that time, as well as special implants to improve his vision.

Afterward Steven—who’d been declared legally blind—made a full recovery, his eyesight restored to 20/20. Steven said it was a miracle; and even with my science-based background, I agreed with him. The rest, as they say, is history. Steven was declared fit to race, and steered the U.S. bobsled team to an Olympic gold in Vancouver.

Calling it a “fairy tale ending” would be a misnomer. Because for good-hearted Steven Holcomb, that was just the beginning. Excited and grateful to have recovered his eyesight, he wanted to pay it forward, by helping Keratoconus sufferers who couldn’t afford the procedure. He and I raised funds through a foundation—called Giving Vision—to award grants to needy patients for travel expenses and, in several cases, the entire cost of the procedure.

These were patients like Freddie Millard, a Los Angeles bus driver who had to give up his beloved route because of his Keratoconus; or Brett Gray, an athlete himself, who’d wrestled for 17 years but could no longer live a normal life due to his failing eyesight; or Mariah Bryant, a hard-working student from Massachusetts, who couldn’t realize her dream of joining the Army because of her deteriorating vision.

Steven and I became close friends over the years, participating in media appearances to promote education about Keratoconus treatments. I’d email him “before and after” videos of a number of grant recipients. Some felt compelled to speak into the camera to thank Steven directly. He’d email me back comments like, “Always makes my day,” “I love to see these,” and “They really, truly mean a lot”.

Responding to one video, in 2012, Steven wrote me a lengthy email: “Honestly,” he said, “it’s one of the few things that validates what I do. I am in a sport that only gets recognition every 4 years. It may sound weird, and I don’t mean it in a bad way…but to hear of people getting help, and to see people finding their lives again is worth every bit.”

We find our purpose in life in unexpected ways. Steven was an internationally renowned bobsledder, and he loved the sport. Still, as he said in a 2014 interview “there’s other people I’m here to help”; and in a 2017 interview “there’s something else that I’m here to do.” Not all of us find our purpose, but I believe my friend found his. It was in helping people—people like Freddy and Brett and Mariah—all of whom went on to recover their eyesight and live happier lives.

The Giving Vision Foundation has restored the eyesight of over one hundred patients. With the Winter Games in full swing and a chill in the air—Steven’s time of year—and in cooperation with Steven’s mom Jean Schaeffer and his long-time manager Brant Feldman, I’ve decided to rename the Foundation: Giving Vision - Steven Holcomb Legacy Foundation.

Jean is here with me in PyeongChang to support our American sliders and to honor Steven and his legacy. We’ll miss him, but we know he’ll always be with us; just as he’ll always be with the bobsledders he inspired, and all those patients whose lives he touched. As I conclude this article, welling with tears, I’m reminded of my favorite quote from Steven: “Tough times don’t last, but tough people do.” Steven, you will last forever.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.