Finding the heart of Shanghai, a haven for Jews in World War II

As I walked through Shanghai’s Hongkou district on a cold February day, I saw the names written in English, seven times, on a museum’s bronze perimeter wall. First name. Middle initial. Then Kessler — my last name.

I was stunned. They were among the Jews, 13,700 of them, who had spent some or all of World War II here and were present during the 1944 census conducted by the occupying Japanese.

Their stories reminded me of my family’s story. I knew that old Shanghai was home to a significant Jewish community, but I didn’t know it had left such a mark on the city.

During my three days here, I saw a decorative wrought-iron Star of David on a front door in the former Jewish ghetto, a synagogue repurposed as a museum, a park plaque in Hebrew and a onetime movie theater and roof garden that had been the heart of Shanghai’s thriving Jewish community.

These remnants, so unexpected, so misplaced, altered my perception of Shanghai and, indeed, China. I had found its heart.

Getting to Shanghai

Between 1938, shortly after the infamous Kristallnacht pogrom of Nazi Germany, and the end of 1941, more than 20,000 Ashkenazi Jews, mostly Austrian, German, Lithuanian and Polish — all stateless refugees — arrived in Shanghai, where they spent the war years.

Shanghai, known then as the “port of last resort,” didn’t require entry papers. But getting there during those years was impossible without the coveted and nearly impossible to obtain laissez-passer, or transit visa. These were issued mainly by two Asian diplomats, Chiune Sempo Sugihara, the Japanese consul general in Kovno (Kaunas), Lithuania, and Ho Feng-Shan, the Nationalist Chinese consul general in Vienna.

Sugihara and Ho worked covertly, contrary to their superiors’ orders and governments’ positions. Both were instrumental in saving thousands of Jewish lives; Sugihara issued about 4,000 transit visas and Ho more than 4,000.

Ho never told anyone what he’d done; his heroics came to light only after his 1997 death in San Francisco, when his daughter, Manli Ho, found the wartime evidence among his belongings. Ho Feng-Shan has since been called the “Chinese Schindler,” after Oskar Schindler, the German industrialist who had saved the lives of more than 1,000 Jews.

Shanghai’s Little Vienna

Remnants of the former Jewish community still exist in the Hongkou district, where refugees first settled and opened delicatessens and bakeries just as they had done on the Lower East Side of New York

The Broadway Cinema, on Huoshan Road, is now a small hotel. Although its beautiful Art Deco facade is fading, with just a bit of imagination, one can envision it as the center of Shanghai’s Jewish social gatherings.

Atop the cinema was the Mascot Roof Garden where concerts were held and people danced. Across the street was Café Roy, another busy gathering spot.

During those years in Shanghai, there were six synagogues and four cemeteries. Today only two of the original temple buildings remain, neither of which is used as a synagogue. One became a government building, and the other, the former Ohel Moshe Synagogue on Changyang Road, became the Shanghai Jewish Refugees Museum.

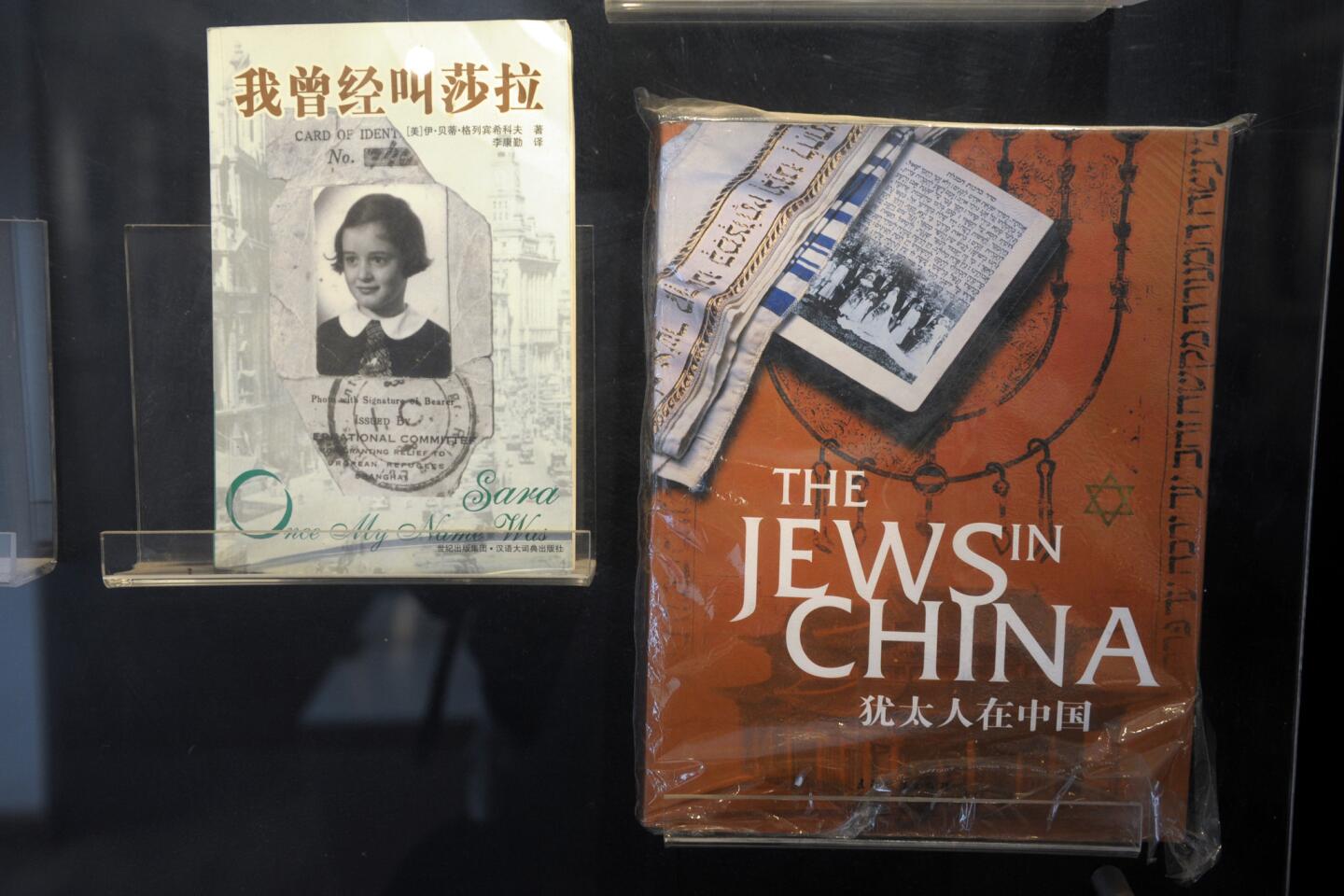

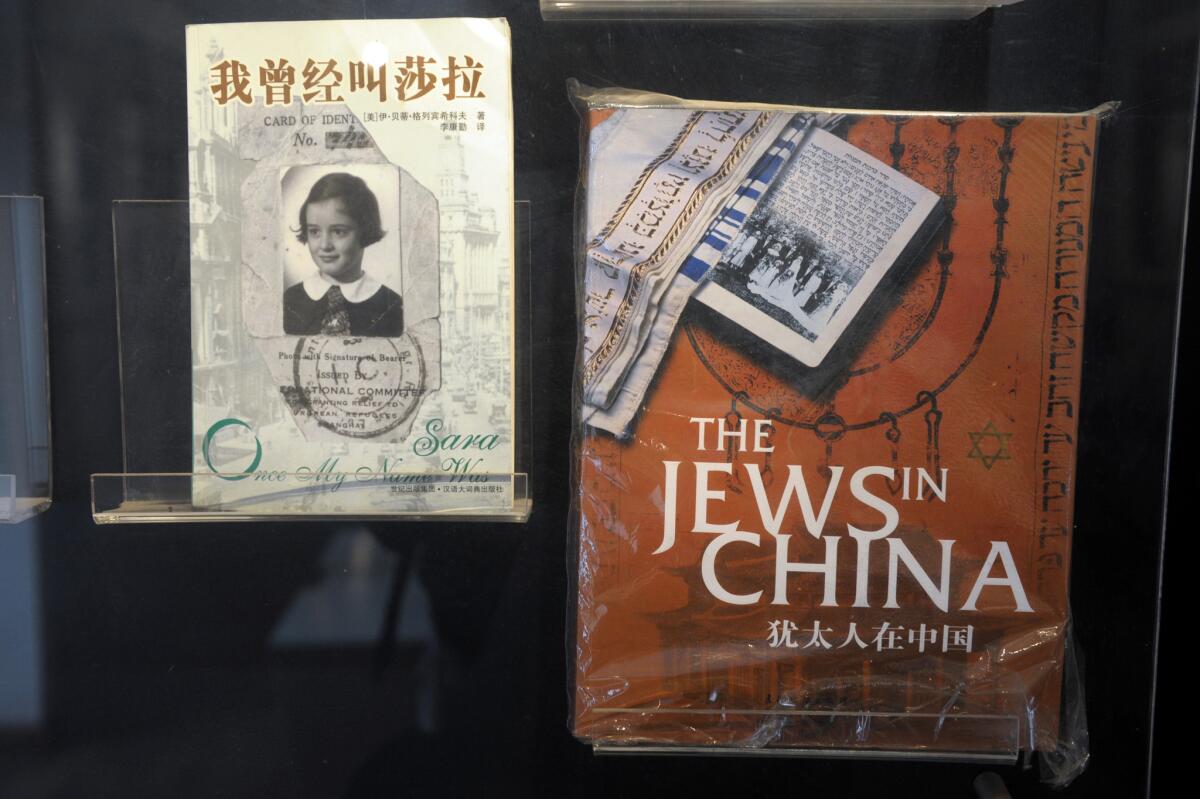

The synagogue was built in 1907 by Russian Jews who had escaped czarist pogroms. (It was moved to its current location in 1927.) The museum complex, lovingly restored, is an excellent repository of wartime items, including English-captioned photos, newspapers and artifacts. There’s also a screening room where I viewed a well-done short film on refugees.

A massive metal sculpture depicting several refugees sits on the museum grounds, as well as that polished perimeter wall engraved with the names of Jews present during the 1944 census, including those seven Kesslers.

Both the sculpture and the wall are powerful reminders of the coupling of Jewish and Chinese history.

The Shanghai Ghetto

In February 1943, at Nazi Germany’s instigation, the commanders in chief of the Japanese army and navy issued a proclamation restricting the residences and businesses of the stateless refugees, in effect establishing the Shanghai Ghetto.

The roughly one square mile of old, narrow lanes and dark, cramped alleyways is bordered by Gongping Road on the west, Tongbei Road on the east, Huimin Road on the south and Zhoujiazui Road on the north.

Although there were no walls enclosing the ghetto, and Jews there were treated benignly relative to their European counterparts, there were deprivations, limited movements and checkpoints.

I walked through the ghetto on a chilly Sunday morning with Shanghai resident Dvir Bar-Gal, an Israeli journalist-documentarian who has been guiding tours of the area for more than 14 years.

In the center of peaceful, manicured Huoshan Park — formerly Wayside Park — stands a large bronze plaque, inscribed in Mandarin, English and Hebrew, that commemorates the “Designated Area for Stateless Refugees.”

Also on Huoshan Road, a four-story building, constructed in 1910, served as the branch office of the New York-based American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee. The JDC provided meals, medical assistance, educational supplies and other necessities to needy refugees.

Bar-Gal led me through some of the old lanes where refugees once lived. Inside one tiny, windowless home, where three Chinese families reside today, many dozens lived during wartime.

At one such ghetto residence on Zhoushan Road, a decorative metal Star of David hung on the diminutive home’s exterior door, a stark reminder of residents past.

When the Japanese were defeated and the war ended, the Jews of Shanghai went on to new lives in Australia, Canada, the U.S. and South America.

The beating heart of humanity had saved thousands of Jews. Not everyone was as lucky, including members of my family, but it’s without a doubt a lesson in compassion worth heeding.

If you go

THE BEST WAY TO SHANGHAI

From LAX, United, Delta, China Eastern and American offer nonstop service to Shanghai, and United, Air China, Korean, JAL, All Nippon, Asiana, China Southern and Delta offer connecting service (change of planes). Restricted round-trip airfare from $1,045, including taxes and fees.

TELEPHONES

To call the numbers below from the U.S., dial 011 (the international dialing code), 86 (the country code for China), 21 (the city code for Shanghai) and the local number. Only landlines in China have area codes and some mobile phones contain 11 numbers.

GETTING AROUND

Taxis are plentiful and inexpensive but few drivers speak English. Have your hotel write out your destination in Chinese characters beforehand. Subways are efficient, convenient and inexpensive.

WHERE TO STAY

Jing An Shangri-La Hotel, 1218 Middle Yan’an Road, Jing An Kerry Centre, West Shanghai; 2209-8888. View rooms in central and trendy location. The hotel also has an excellent health club and indoor sky-dome pool; its Chi spa with enormous spa suites should not be missed. Doubles from $374.

WHERE TO EAT

Mercato, No. 3 the Bund, sixth floor (corner of Guangdong); 6321-9922. Good Italian fare in a post-renaissance building with a great view of the Bund.

1515 West Chophouse & Bar, Jing An Shangri-La Hotel, 2203-8889. Reminiscent of an old New York-style grill, with steaks imported from Australia. Will impress die-hard carnivores.

TO LEARN MORE

For tours of Shanghai’s old Jewish quarter, 1300-214-6702. Half-day group tours are $68 per person.

For general information and planning, www.shanghaichina.ca

Chinese Consulate-General, 443 Shatto Place, Los Angeles; (213) 807-8088, losangeles.china-consulate.org/eng/. Information on visas.

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.