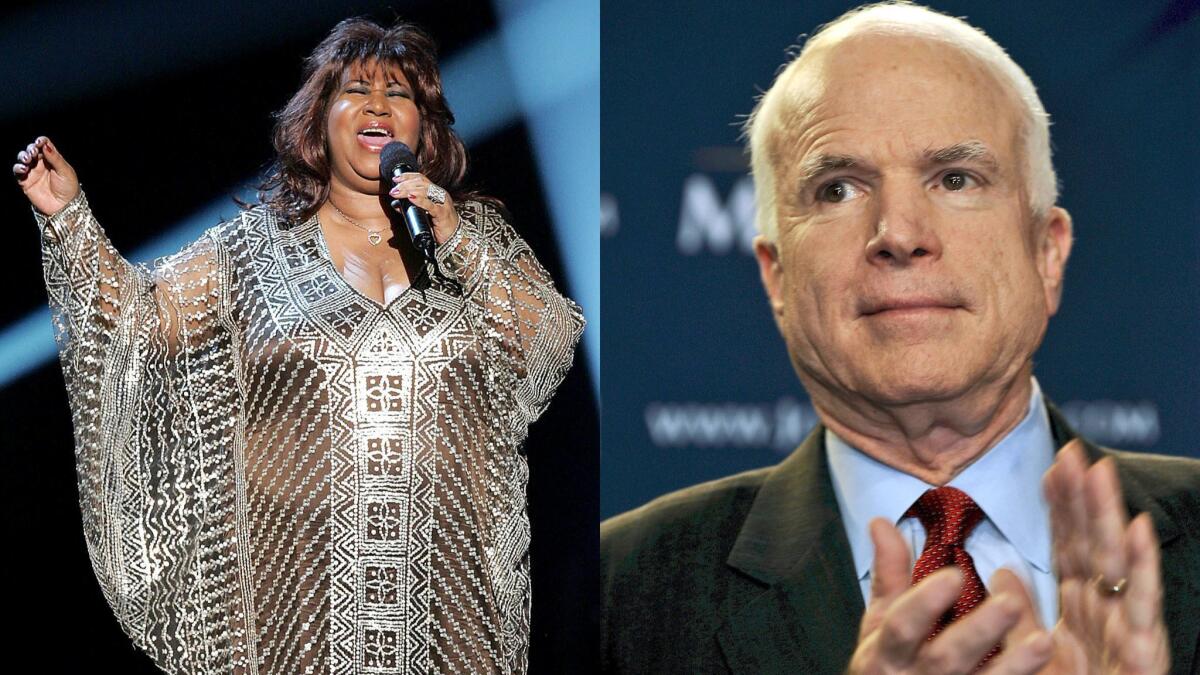

Column: What the funerals of John McCain and Aretha Franklin tell us about ourselves

Funerals for two of this country’s most remarkable citizens took place over the long Labor Day weekend.

The spectacles — and I mean that in the best sense of the word — showcased the beauty and ugliness of our country at this uniquely messy moment in American history.

Arizona Sen. John McCain, the 81-year-old maverick, was buried in Annapolis, Md., on Sunday after a service in Washington on Saturday that was both a celebration of his life and an unchoreographed repudiation of its most famous uninvited guest.

On Friday in Detroit, Aretha Franklin, the 76-year-old Queen of Soul, was laid to rest after a “home going” that lasted more than six hours. Her memorial featured mind-blowing musical performances that honored but never eclipsed the sublime singer herself, oblique digs at President Trump and a racist joke at the expense of Ariana Grande, made by a male pastor who also appeared to grope the young star’s breast.

Why should funerals be immune to the kinds of disagreements, controversies and displays of male privilege we have come to expect in every other part of life?

::

Last year, when McCain learned he was terminally ill with glioblastoma, a lethal form of brain cancer, he set about planning his funeral. He would prove to be as pesky in death as he was in life. Former Presidents Obama and George W. Bush, who had both thwarted his quest for the presidency, would eulogize him.

But President Trump, who has insulted the ideal that McCain valued most — service to country — was not to be invited. Nor was Sarah Palin, whom he had lifted to fame from obscurity as the governor of Alaska in 2008 when he reluctantly tapped her to be his vice presidential running mate. In his most recent book, “The Restless Wave,” he confessed that he wished he’d chosen then-Democratic Sen. Joe Lieberman as his running mate. Not inviting Palin to his funeral was as close as he ever really came to apologizing for unleashing the woefully unprepared Alaskan on the world.

But snubbing Trump was a thing of dark beauty — not just understandable, but laudable.

Trump supporters were apoplectic, and instantly appointed themselves arbiters of appropriate behavior. They were especially appalled that Meghan McCain, the senator’s 33-year-old daughter, delivered a pointed rebuke to Trump. How dare she — and the other speakers — politicize a politician’s death, as if, somehow, one could separate the essence of the man from four decades of his life’s work, from his very identity?

“Many of those watching at home were disgusted by the politicization of a man’s death,” wrote John Nolte on the pro-Trump alt-right-friendly Breitbart website, “and used social media to comment on the irony-filled and inappropriate spectacle of elites using a funeral service (of all places) to attack others over partisanship and a lack of decency.”

The idea that Trump fans would ever presume to hold anyone accountable for a “lack of decency” is a joke that writes itself.

McCain’s funeral was a distillation of the man himself: passionate, prickly, bipartisan and anti-Trump. But most of all, patriotic.

::

I watched many snippets of Franklin’s beautiful memorial service at Greater Grace Temple in Detroit.

Franklin was a creature of the black church, of gospel choirs and of Detroit, the place she considered home. She was an icon of civil rights, and women’s rights, and you had to feel sorry, just a little bit, for some of the performers who sought to pay her tribute. Quite simply, no one could sing like Aretha.

Her struggles were different from McCain’s, but oh how she used her gifts to prevail over the obstacles in her life and become one of the 20th century’s most treasured musical artists.

Then came a moment during her service that stood out as a microcosm of what women — not just women like Franklin, but all women — have had to deal with forever, particularly in places like church, where men run the show and expect women to be subservient.

Grande, 25, was onstage, singing the classic “(You Make Me Feel Like) A Natural Woman.”

Later, Grande would be criticized on Twitter — where else? — for her choice of attire: a very short but modest black dress. Honestly, Franklin was the embodiment of empowered female sexuality, so who cares about a skirt length? Especially since what happened next was actually terrible.

After Grande finished singing, Bishop Charles H. Ellis III, who officiated at Franklin’s funeral, beckoned the young star to the microphone.

“When I saw ‘Ariana Grande’ on the program,” he said, “I thought that was something new at Taco Bell.” Grande is of Italian heritage, but that’s hardly the point. As Ellis mocked her name, he clutched her waist, his right hand seeming to grope the side of her right breast for a good long 30 seconds as she tried in vain to pull away, or at least maintain some distance.

I defy you to watch the clip without a physical sensation of revulsion, and horror that a 60-year-old man would virtually assault a young woman this way with so many people looking on.

Ellis soon apologized, both for his tasteless joke and for the way he touched her, although he denied he did it on purpose.

“It would never be my intention to touch any woman’s breast,” he told the Associated Press at the cemetery where Franklin was interred on Friday. “Maybe I crossed the border, maybe I was too friendly or familiar, but again I apologize.”

What he did was not friendly or familiar. It was abusive and wrong.

Two of our icons have left us.

McCain’s memorial showed that even in death, it is possible to remain true to one’s principles, and to get the last word in a morally satisfying way.

Frankin’s home going allowed us to see that the very system of patriarchy she worked so hard to overcome is a battle that still rages. The respect she demanded requires a constant struggle.

For better or worse, America, this is us.

Twitter: @AbcarianLAT

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.