How Frank Gehry’s L.A. River make-over will change the city and why he took the job

Frank Gehry and the Los Angeles River: It’s a combination that makes zero sense (if you’re looking strictly at Gehry’s resume) and follows a natural logic (if you think about the interest the architect’s work has long shown in L.A.’s linear infrastructure and its overlooked, harder-to-love corners).

And it might give Mayor Eric Garcetti a way to confront the growing conventional wisdom that he is sometimes paralyzed by caution, gun-shy about big-ticket or controversial efforts to remake the city.

The 86-year-old Gehry has been working for about a year on a wide-ranging new plan for the river. His client is the L.A. River Revitalization Corp., a nonprofit group founded by the city in 2009 to coordinate river policy.

Though Gehry’s firm has taken on a few master plans, including an ill-fated attempt to redesign Atlantic Yards in Brooklyn for the developer Bruce Ratner, the office is best known for virtuoso stand-alone buildings including Walt Disney Concert Hall and the new Louis Vuitton Foundation in Paris.

Yet Gehry insists that he isn’t interested in the river as the site for new landmarks. He says he told the Revitalization Corp. board members who first visited his office last year that he would take on the job only if he could look at the river primarily in terms of hydrology.

“They came to see me and said they were heading up a committee for Mayor Garcetti and said we have this wonderful river, 51 miles, and that if we could brand it, give it visual coherence, it could become something special,” the architect said in a conversation at the offices of Gehry Partners.

“I said, ‘Oh, you want me to be Olmsted,’” a reference to Frederick Law Olmsted, one of the designers of Central Park. “I told them I’m not a landscape guy. I said I would only do it on the condition that they approached it as a water-reclamation project, to deal with all the water issues first.”

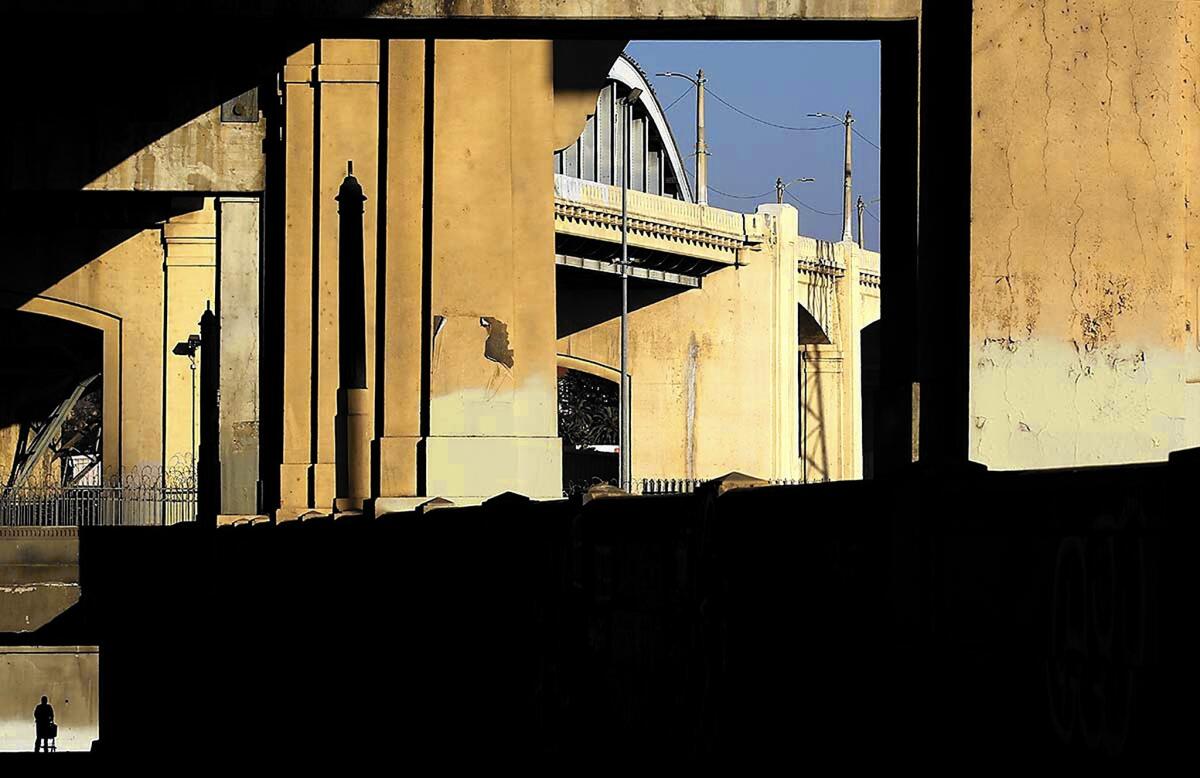

Since the river was wrapped in concrete by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, beginning before World War II, it has operated as an infrastructural machine with one central task: to keep storm-water runoff from flooding Los Angeles by whisking it south toward Long Beach and out to sea. On most days the relative trickle in the concrete channel is treated wastewater from plants upriver.

Gehry thinks it could be turned into an entirely different kind of machine, one that could store and even treat storm water. Capturing more storm water could also allow the city and region to save some of the money they now spend importing water from around the West, helping finance new park space along or even spanning the river. “I think we’re wasting a lot of water at a time when we need it,” he said.

The architect has also long been fascinated with Los Angeles as a city defined by huge, linear public-works projects. In that sense the river is a relative, an overlooked cousin, of Wilshire Boulevard (which Gehry has frequently called the city’s true downtown) and L.A.’s freeways.

Gehry has been assembling a group of engineers and designers for meetings at his office. They include Richard Roark, a partner in the Philadelphia-based landscape architecture firm Olin, the Dutch water-management expert Henk Ovink, and consultants from the engineering firm Geosyntec.

Inside Gehry Partners the project has been spearheaded by two of the architect’s younger partners, Tensho Takemori and Anand Devarajan.

The group has developed a preliminary presentation, a basic pitch, that Gehry and Revitalization Corp. leaders can give to elected officials and potential private funders. It stresses how little sense it makes to prohibit the public from using the river or its banks when risk of flooding is low — which means the vast majority of the time.

Omar Brownson, executive director of the Revitalization Corp., calls this the “Gordian knot” of L.A. River planning. The challenge is allowing public access to the river — crucial in a city that remains desperately short of park space — without jeopardizing flood control.

All of which raises an obvious question: Why would City Hall want to hand over a project that is primarily hydrological to Frank Gehry, of all people?

The first answer is that Gehry’s office, which has made its technological sophistication a calling card, offered the ability to help the city quickly create a new digital map of the river to guide future planning.

Working with the technology firm Trimble, which acquired the architect’s spinoff company Gehry Technologies last year, Gehry’s office has already produced a three-dimensional, so-called point-cloud model for about 70% of the river. The 3-D digital model, along with new high-definition photography, “will give us an objective starting point for the river that everybody can work on,” Takemori said.

The second part of Gehry’s appeal to City Hall has to do with the simple calculus of day-to-day politics. Gehry — who has been working pro bono on the river research so far — has the celebrity, connections and force of personality to consolidate political support and fundraising efforts. This is especially meaningful given the dozens of cities and jurisdictions that have a say over the river, about a third of which is outside the Los Angeles city limits.

For Garcetti, the appeal of the river as the anchor of a major policy and civic-design initiative is clear. It offers the chance to tackle several major issues in a single project, including public health (thanks to new riverside parks and walking and biking paths), climate change and affordable housing (if public land can be used along the river for new construction).

Garcetti has faced criticism since he was a City Council member for his preternatural caution. Here is a chance to swing for the fences.

In other ways, though, the river is a vexing and contradictory opportunity. Unlike most public-works projects that mayors hope to attach their names to, this one is not about building impressive new infrastructure. It has more to do with removal and exposure, with dismantling the physical, legal and psychological barriers that have kept the public out.

In neighborhoods near the river marked by anxiety about rising housing prices — Frogtown is one — there is concern that whatever plan the city and county come up with, it will be overwhelmed by a speculative rush of development.

The irony is that the original effort to wrap the river in concrete was executed in part to please big landowners and developers, to protect their property from seasonal flooding and keep the Southern California growth machine humming.

The news that the mayor is handing off planning to Gehry’s office is already upsetting longtime river advocates, including Lewis MacAdams, co-founder of Friends of the Los Angeles River.

Their skepticism is understandable. If the Gehry-led group helps shape a sturdy new consensus about remaking the river as a civic amenity, Garcetti’s gamble will have been worth it. If renewed attention to river planning gives rise to a truly substantive public conversation about water policy, drought and climate change in Southern California, even better.

If on the other hand it becomes the vehicle for attempts by Gehry’s firm to turn out grand, signature infrastructure in the way it has sometimes turned out grand, signature buildings, or generates more photo ops than progress, it will undermine important work on the river that goes back decades.

Gehry insists that his effort will be complementary with earlier and ongoing ones, including so-called Alternative 20, a federal plan that calls for dramatically redesigning an 11-mile stretch of the river near downtown.

In at least one fundamental way, though, the architect’s vision for the river will probably break markedly from what’s come before. Though there is no practical way to remove all or even most of the concrete, earlier designs have advertised themselves primarily through soft-focus, Arcadian renderings of newly green riverbanks.

Gehry made a name for himself by adopting the generic, workaday built environment of Los Angeles — its chain link and corrugated metal — as the basis of his architecture. The paved and unlovely landscape of the L.A. River, which at certain points reaches a monumental scale, like a freeway without cars, is for him not an alien setting but a familiar, even reassuring one.

“I don’t see tearing out the concrete,” Gehry said. “It’s an architectural feature, and I can see ways of incorporating it into what we’re doing.”

christopher.hawthorne@latimes.com

ALSO:

L.A. city officials want to get you out of your car -- here’s their plan

Grand jury report critical of Kings County’s suits against bullet train draws fire

100 days, 100 nights: How LAPD is dealing with rumors, gangs and fear

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.