Must Reads: How a 50-year-old design came back to haunt Boeing with its troubled 737 Max jet

A set of stairs may have never caused so much trouble in an aircraft.

First introduced in West Germany as a short-hop commuter jet in the early Cold War, the Boeing 737-100 had folding metal stairs attached to the fuselage that passengers climbed to board before airports had jetways. Ground crews hand-lifted heavy luggage into the cargo holds in those days, long before motorized belt loaders were widely available.

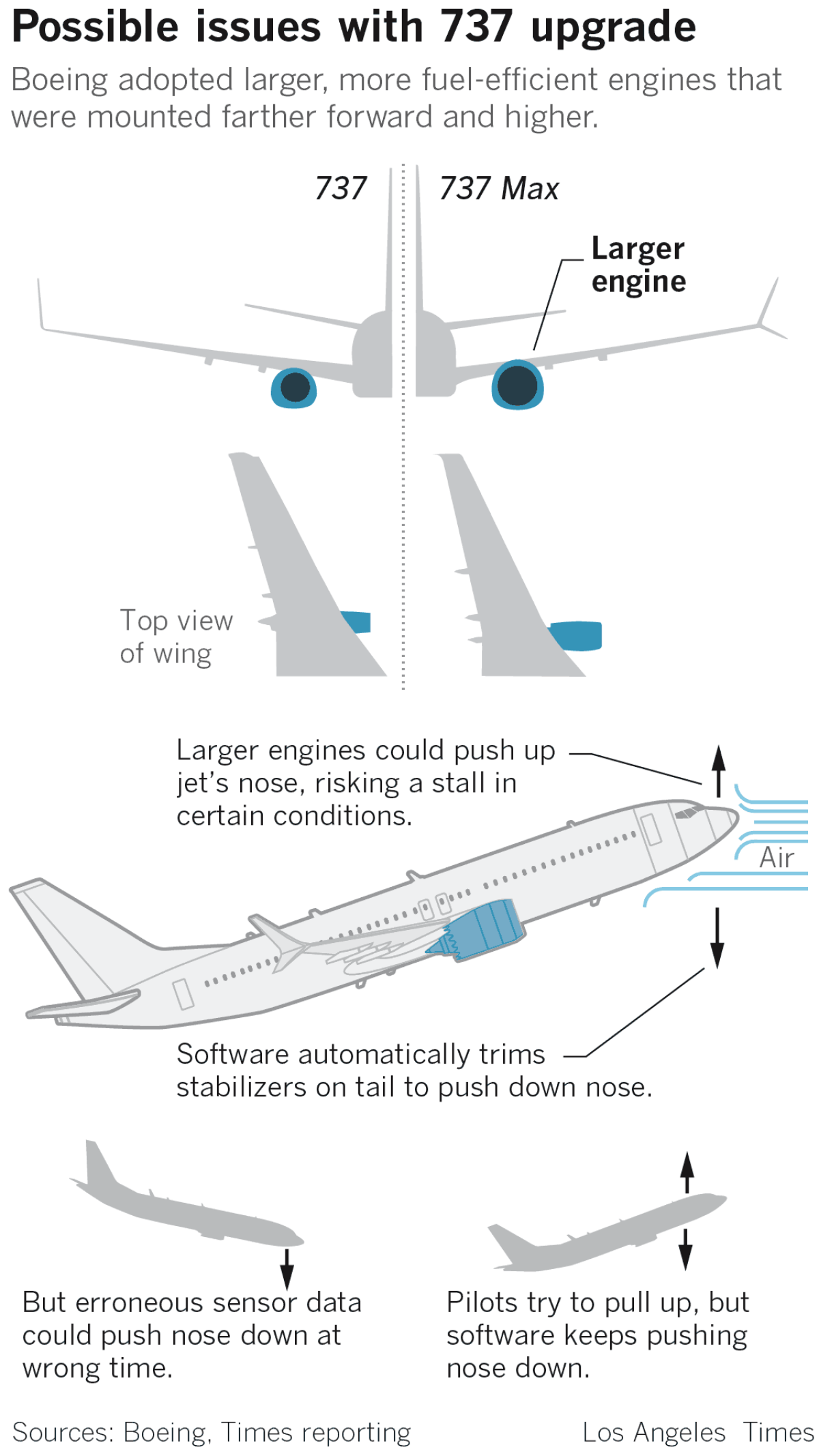

That low-to-the-ground design was a plus in 1968, but it has proved to be a constraint that engineers modernizing the 737 have had to work around ever since. The compromises required to push forward a more fuel-efficient version of the plane — with larger engines and altered aerodynamics — led to the complex flight control software system that is now under investigation in two fatal crashes over the last five months.

Boeing’s problems deepened Thursday, when the company announced it was stopping delivery of the aircraft after the Federal Aviation Administration’s decision Wednesday to ground the aircraft.

“We continue to build 737 Max airplanes, while assessing how the situation, including potential capacity constraints, will impact our production system,” the Chicago company said in a statement.

The crisis comes after 50 years of remarkable success in making the 737 a profitable workhorse. Today, the aerospace giant has a massive backlog of more than 4,700 orders for the jetliner and its sales account for nearly a third of Boeing’s profit.

But the decision to continue modernizing the jet, rather than starting at some point with a clean design, resulted in engineering challenges that created unforeseen risks.

“Boeing has to sit down and ask itself how long they can keep updating this airplane,” said Douglas Moss, an instructor at USC’s Viterbi Aviation Safety and Security Program, a former United Airlines captain, an attorney and a former Air Force test pilot. “We are getting to the point where legacy features are such a drag on the airplane that we have to go to a clean-sheet airplane.”

Few, if any, complex products designed in the 1960s are still manufactured today. The IBM 360 mainframe computer was put out to pasture decades ago. The Apollo spacecraft is revered history. The Buick Electra 225 is long gone. And Western Electric dial telephones are seen only in classic movies.

Today’s 737 is a substantially different system from the original. Boeing strengthened its wings, developed new assembly technologies and put in modern cockpit electronics. The changes allowed the 737 to outlive both the Boeing 757 and 767, which were developed decades later and then retired.

Over the years, the FAA has implemented new and tougher design requirements, but a derivative gets many of the designs grandfathered in, Moss said.

“It is cheaper and easier to do a derivative than a new aircraft,” said Robert Ditchey, an engineer, aviation safety consultant and founder of America West Airlines, which purchased some of the early 737 models. “It is easier to certificate it.”

But some aspects of the legacy 737 design are vintage headaches, such as the ground clearance designed to allow a staircase that’s now obsolete. “They wanted it close to the ground for boarding,” Ditchey said.

Andrew Skow, founder of Tiger Century Aircraft, which develops cockpit safety systems, and a former Northrop Grumman chief engineer, said Boeing has had a good record modernizing the 737. But he said, “They may have pushed it too far.”

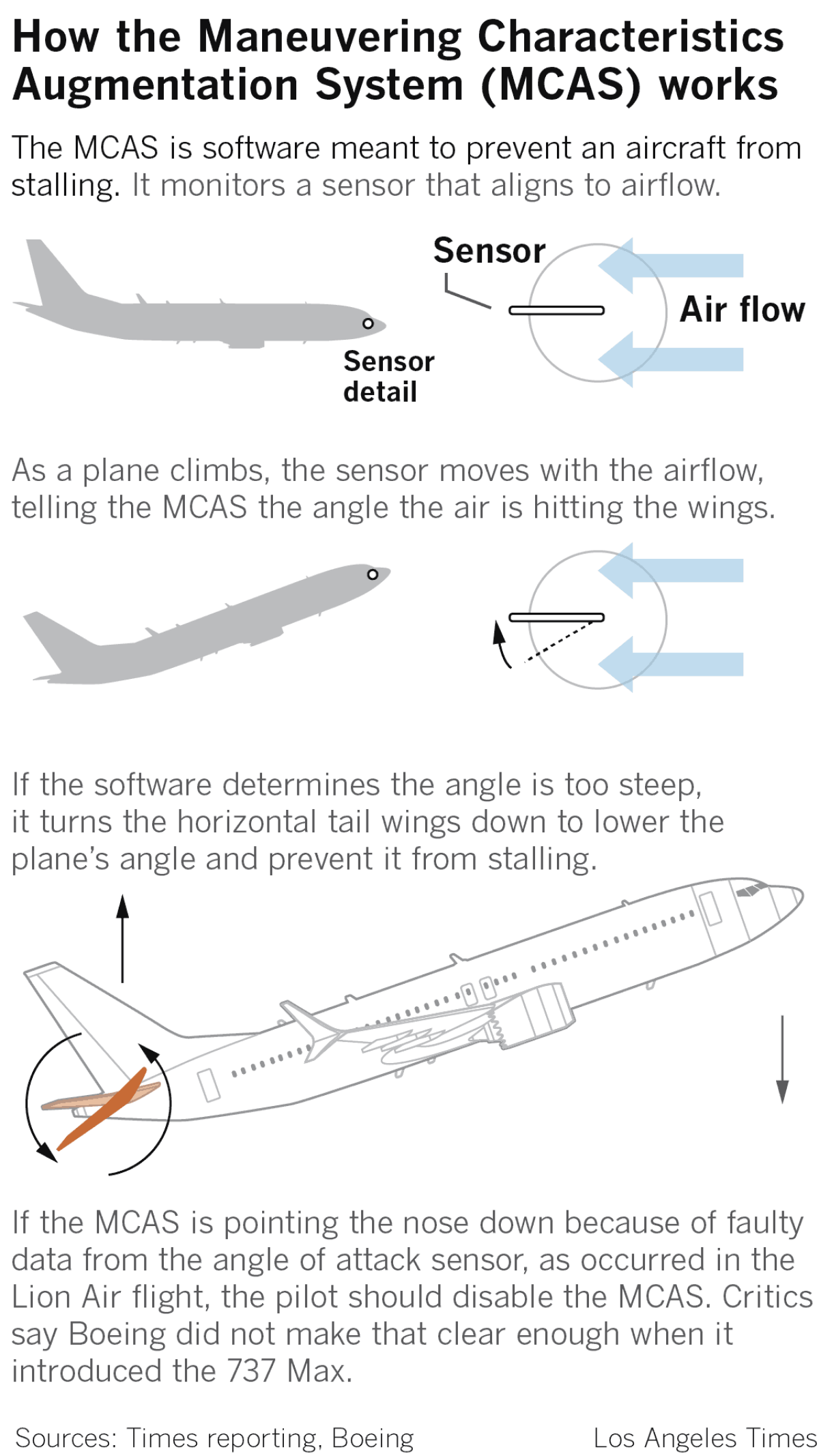

To handle a longer fuselage and more passengers, Boeing added larger, more powerful engines, but that required it to reposition them to maintain ground clearance. As a result, the 737 can pitch up under certain circumstances. Software, known as the Maneuvering Characteristics Augmentation System, was added to counteract that tendency.

It was that software that is believed to have been involved in a Lion Air crash in Indonesia in October.

The software erroneously thought the aircraft was at risk of losing lift and stalling — because of a malfunctioning sensor — and ordered the stabilizer at the rear to put it into a series of sharp dives that ultimately caused the plane to crash into the Java Sea.

What happened on the Ethiopian Airlines flight is less clear, but tracking data show that it also encountered sharp changes in its vertical velocity and at one point in its climb after takeoff lost 400 feet of altitude. The FAA grounded the jetliner Wednesday, saying that new satellite data showed the Ethiopian Airlines flight dynamics were “very close” to those of the Lion Air jet.

Ethiopia sent “black box” recording devices recovered from the crashed jet to France for analysis, after refusing to hand them over to U.S. authorities. The U.S. National Transportation Safety Board still plans to send investigators to France to help its Bureau of Inquiry and Analysis for Civil Aviation Safety.

Airline crashes seldom are caused by a single factor, and the two 737 accidents may yet involve poor maintenance, pilot errors and inadequate training. But it appears increasingly likely that Boeing’s software system and the company’s lack of recommendations for pilot training on it may have played an important role in the crashes.

The entire need for the software system is fundamental to the jet’s history.

The bottom of the 737’s engines are a minimum of 17 inches above the runway. By comparison, the Boeing 757 has a minimum clearance of 29 inches, according to Boeing specification books. The newer 787 Dreamliner has 28 inches or 29 inches, depending on the engine.

The 737 originally was equipped with the Pratt & Whitney JT-8 series jets, which had an inner fan diameter of 49.2 inches. “They looked like cigars, long and skinny,” Moss said.

By comparison, the LEAP-1b engines on the Max 8 have a diameter of 69 inches, nearly 20 inches more than the original. There wouldn’t be enough clearance without some kind of modification.

In the 737-300, which came after the original planes sold in West Germany, Boeing came up with an unusual fix: It created a flat bottom on the nacelle (the shroud around the fan), creating what pilots came to call the “hamster pouch.”

“They made it work,” said Ditchey, whose America West was one of the original customers of the 737-300.

But the LEAP engines required an even bigger change. Boeing redesigned the pylons, the structure that holds the engine to the wing, extending them farther forward and higher up. It gave the needed 17 inches of clearance. The company also put in a higher nose landing gear.

The change, however, affected the plane’s aerodynamics. Boeing discovered the new position of the engines increased the lift of the aircraft, creating a tendency for the nose to pitch up.

The solution was MCAS, which ordered the stabilizer to push down the nose if the “angle of attack” — or angle that air flows over the wings — got too high. The MCAS depends on data from two sensors. But on the Lion Air flight, the MCAS relied on a sensor that was erroneously reporting a high angle of attack when the plane was nowhere near a stall.

The pilots tried to counteract the nose-down movements by pulling back on the yoke. But even pulling with all their might they could not counteract the forces, according to data in a preliminary accident investigation report.

Skow criticized Boeing’s MCAS system, saying it acted only on the basis of angle of attack. The Lion Air jet was traveling so fast that when MCAS ordered the stabilizer to pitch the nose down it was a violent reaction. The software should have factored in air speed, he said, which would have better calibrated the pilots’ reaction.

Skow’s firm has developed a cockpit display system, known as Q-Alfa, which he says would have identified the failure of the angle of attack sensor and allowed the crew to abort the takeoff. “We believe we could have prevented the accident,” he said.

If the results of the investigation do not undermine the fundamental design of the aircraft, then the 737 Max’s future may not be in peril, aviation experts said. It may turn out all that’s needed is a software fix or additional pilot training.

The 737 has survived other crises. In a 1988 accident on a flight between Honolulu and Hilo, the entire top of the plane came off in an explosive decompression. A flight attendant was sucked out and 65 passengers and crew were injured. It was blamed on faulty lap joints in the aluminum skin of the fuselage, which Boeing reengineered.

“The 737 is the most successful commercial jet ever produced,” said John Cox, an air safety expert and veteran pilot, adding that commonality among its models helps airlines with pilot training. “It is nearing the end of its production life. The technology will eventually drive Boeing to a replacement.”

Follow me on Twitter @rvartabedian

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.