Historian travels through time to detail the first adventures by car

It took Peter Blodgett just under an hour and a half one recent afternoon to drive from San Marino to Corona del Mar. It’s a fact worth noting, given that he’d come to talk about car travel in the West.

Not as we experience it today — with GPS, cruise control, cup holders, Bluetooth — but as it rolled out at the turn of the last century.

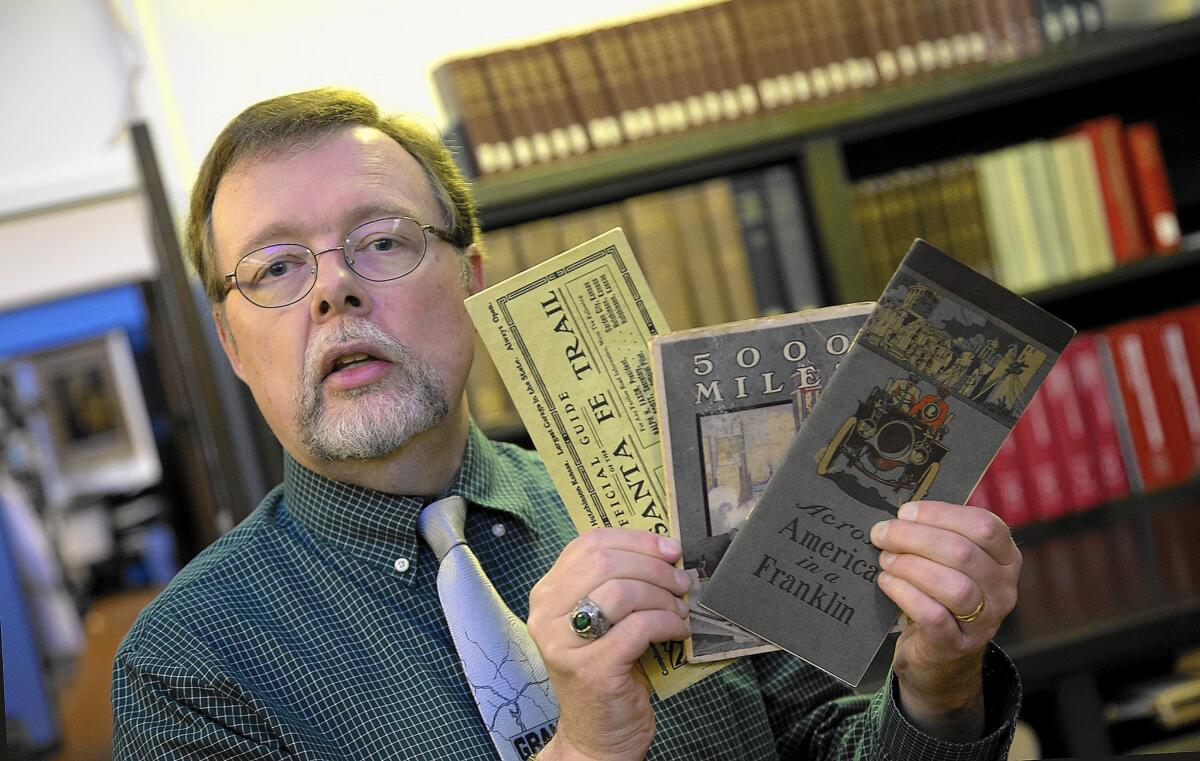

Blodgett, curator of Western historical manuscripts at the Huntington Library, is also the editor of a new book: “Motoring West: Automobile Pioneers, 1900-1909.” During those years, he said, the 50-mile journey he’d just made would have swallowed up most of a day.

And before braving the return trip, a traveler certainly would have stopped for the night — no doubt grateful for the chance to clean up and rest.

Automobile travel, Blodgett explained to a gathering at the Sherman Library and Gardens, at first was a bumpy, dusty affair.

Most early American cars took their design cues from the horse-drawn buggies they soon would make obsolete. They lacked sides and roofs and often even the most rudimentary windshields.

If it rained, you got soaked. Pebbles and insects would ping you. As for the roads, Blodgett said, displaying a map of land west of the Mississippi, circa 1905: “You will see the mountain ridges. You will see the rivers. The one thing you won’t see here is highways.”

A 1904 survey recorded 2.15 million miles of rural roads nationwide, about 154,000 of which were even the slightest bit surfaced — meaning the gravel had been mixed with a binder to keep it slightly more in place. The idea of the road, Blodgett said, “was more aspirational than actual.”

Summer, of course, is prime time for road trips.

But who hasn’t set off with big dreams, only to crash into reality’s roadblocks? Flat tires. Screaming kids. Those romantic, spontaneous, let’s-not-make-firm-plans that turn into bleary-eyed hunts for any room at any inn.

Perhaps a dose of historical perspective can remind us just how easy we have it today.

In 1900, a West Coast road trip was a true act of daring. There weren’t guidebooks or maps or gas stations or motels or rest stops with food courts — or even auto mechanics, except in big urban areas.

For “Motoring West,” the first of a four-volume series, Blodgett dug up accounts of car travel from the pages of publications such as Scientific American, Outing and Munsey’s Magazine.

Some described encountering people who’d never before seen an automobile. One small boy “was frightened and commenced to cry violently,” when the author pulled up to ask about road conditions.

A 1905 article called “Camping Out with an Automobile” suggested that travelers find topographical, geographical and survey maps at the library, then use tracing paper to make custom maps by marking key information such as rivers and towns.

That same piece advised traveling with two cars of the same make so that they could swap spare parts and, in case of a breakdown, one could tow the other.

Car trouble was in fact quite common, given that rains turned routes into “gumbo” mud and trails were so deeply rutted by wagon wheels that cars banged against the resulting mounds of dirt.

Early road trippers frequently reported rescues by farmers, whose horses hauled vehicles out of ditches or streams they had tried — and failed — to ford.

At a time when being behind the wheel still was a novel experience, quite a few of the articles read like how-to guides.

One from 1902, called “A Practical Automobile Touring Outfit,” suggested having clothing made of kangaroo hide because of its ability to shed rain. “The Automobile Vacation” (1907) included a long list of recommended supplies for a car trip: tire inner tubes and valves, “rawhide tire bandages,” a “hydrometer to test gasoline,” extra oil, seat and lamp covers to protect against dust and mud, and “goggles for all passengers.”

It’s easy to get lost in, and perhaps stressed out by, such practical details — now just as it was a century ago.

But that would be missing the point, Blodgett said, and many of the writers included in his anthology likely would have agreed.

Because of the car, they wrote, for the first time they were getting to explore the country on their own terms, not limited by a train route or a horse’s endurance.

“It is closing in an embrace with mother earth, yet not locked with her in the compass of a day’s slow tramp, but free to roam, to camp, and to change your ground at will…” said the writer of a 1905 piece, “Camping Out with an Automobile.”

It is that feeling of endless possibility that still grabs us as we struggle to cram the last bags into the trunk.

Follow City Beat @latimescitybeat on Twitter and at Los Angeles Times City Beat on Facebook.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.