Homelessness became a crisis in L.A. during the 1980s, but the city struggled to act

In less than two weeks, Los Angeles voters will decide the fate of a bond measure to help build low-cost housing for those now living on the streets.

Statistics show Southern California’s homeless problem has gotten worse in recent years, which has helped push homelessness to the top of L.A.’s civic agenda.

But the city has struggled with homelessness for decades.

Leaders first considered the scope of the problem in the 1980s, when L.A.’s homeless population began to swell — particularly around downtown. Despite some temporary measures, the city struggled to address what it acknowledged was a major problem.

Here is a guide to that period, taken from the pages of The Times:

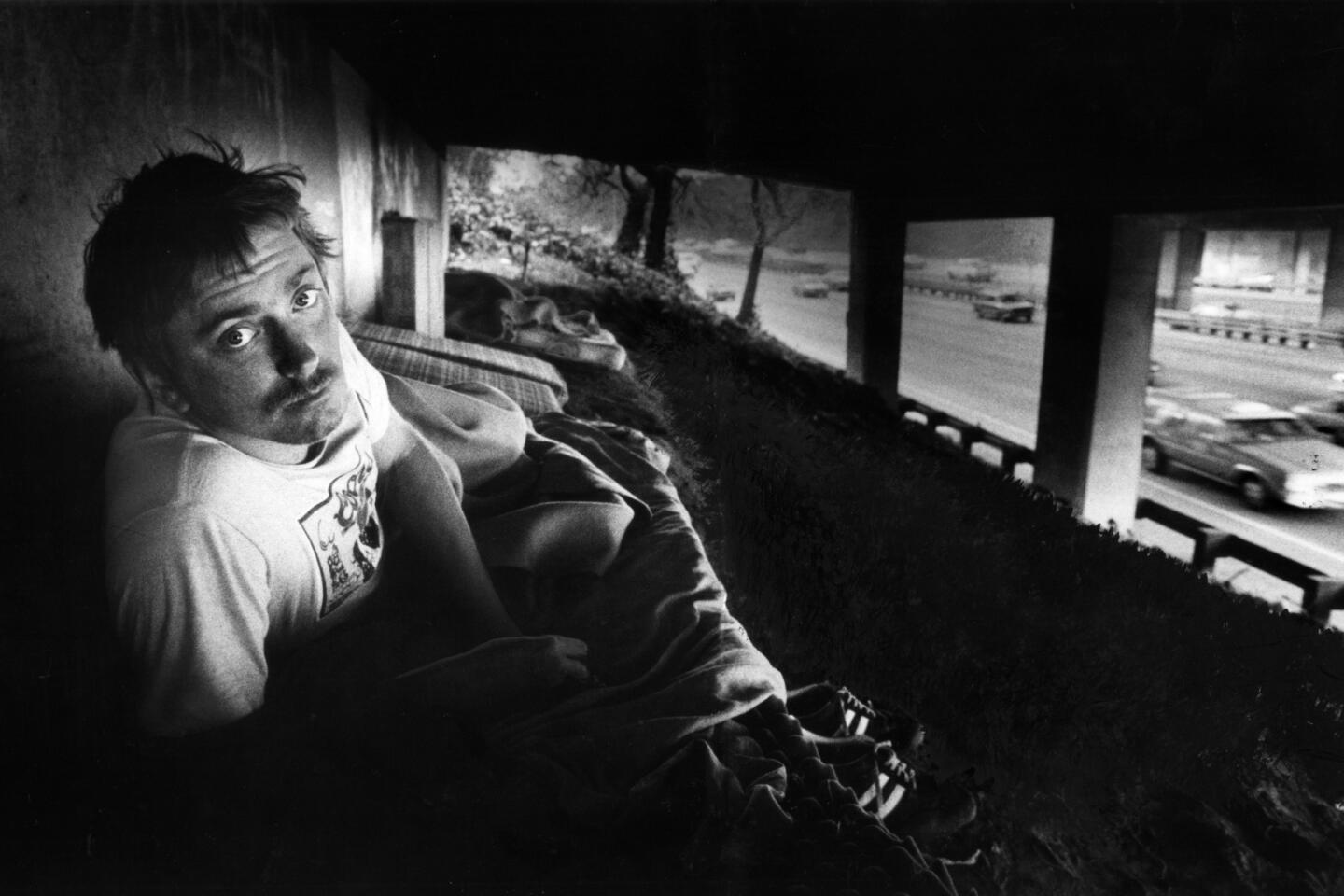

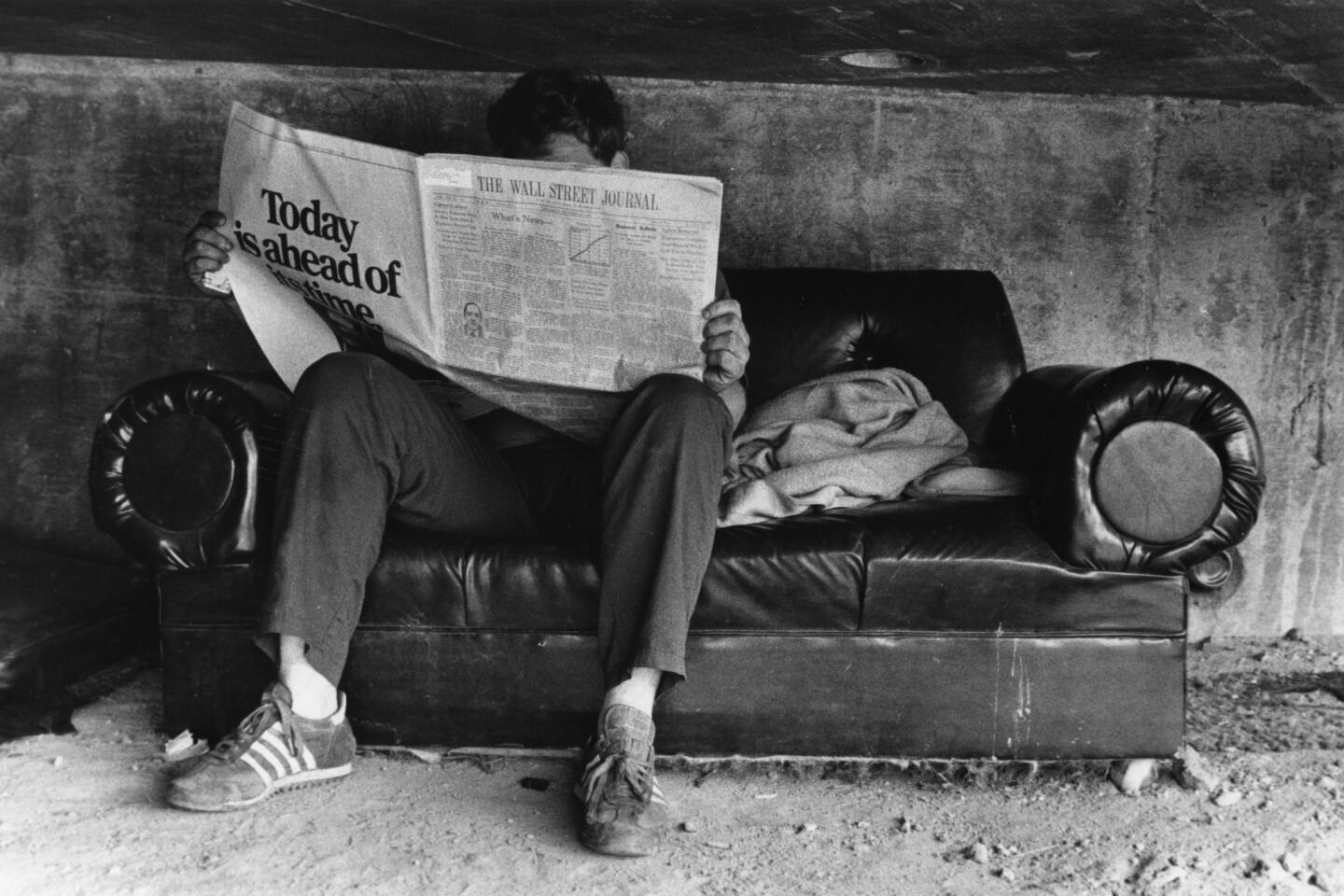

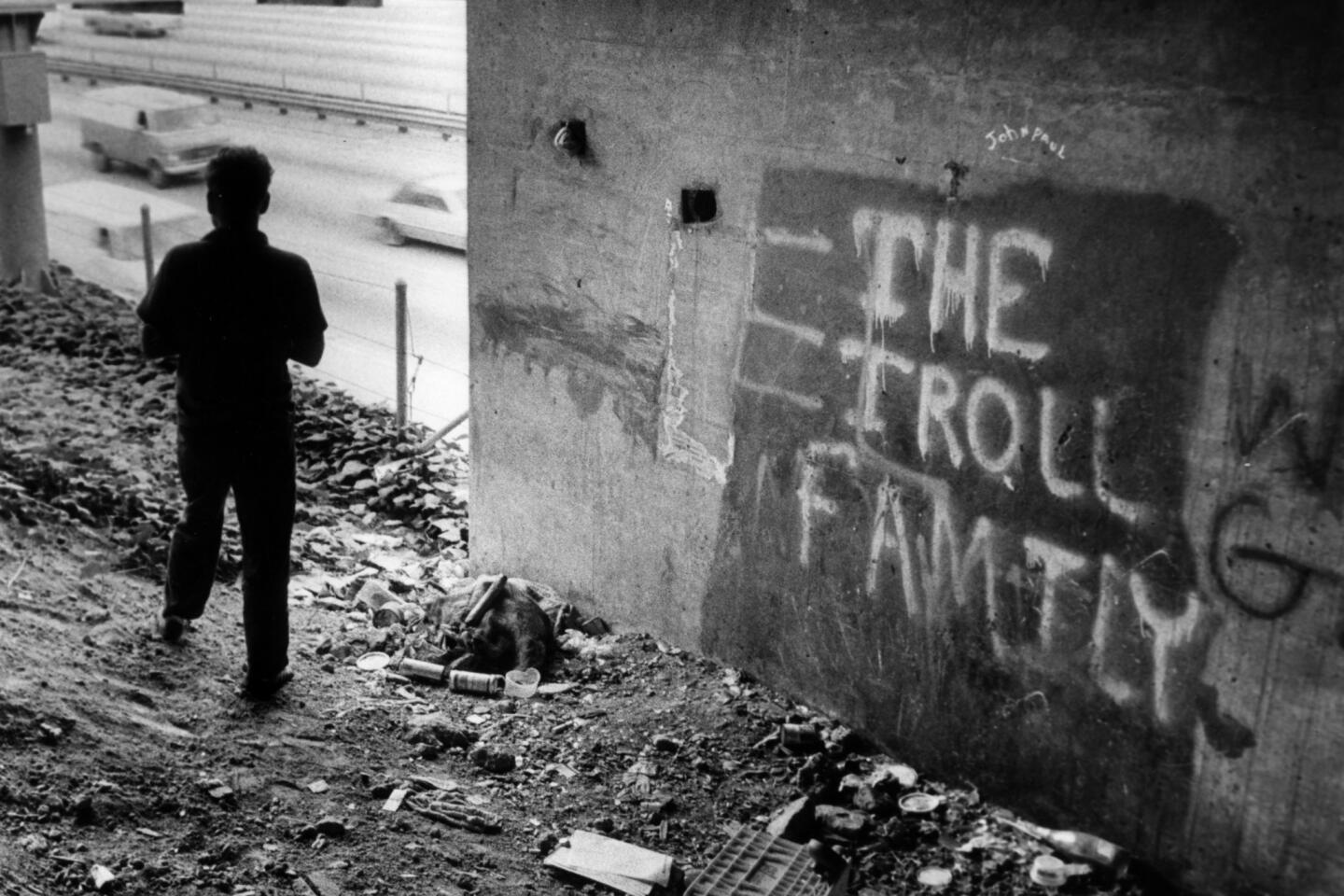

1982: Living under the freeway

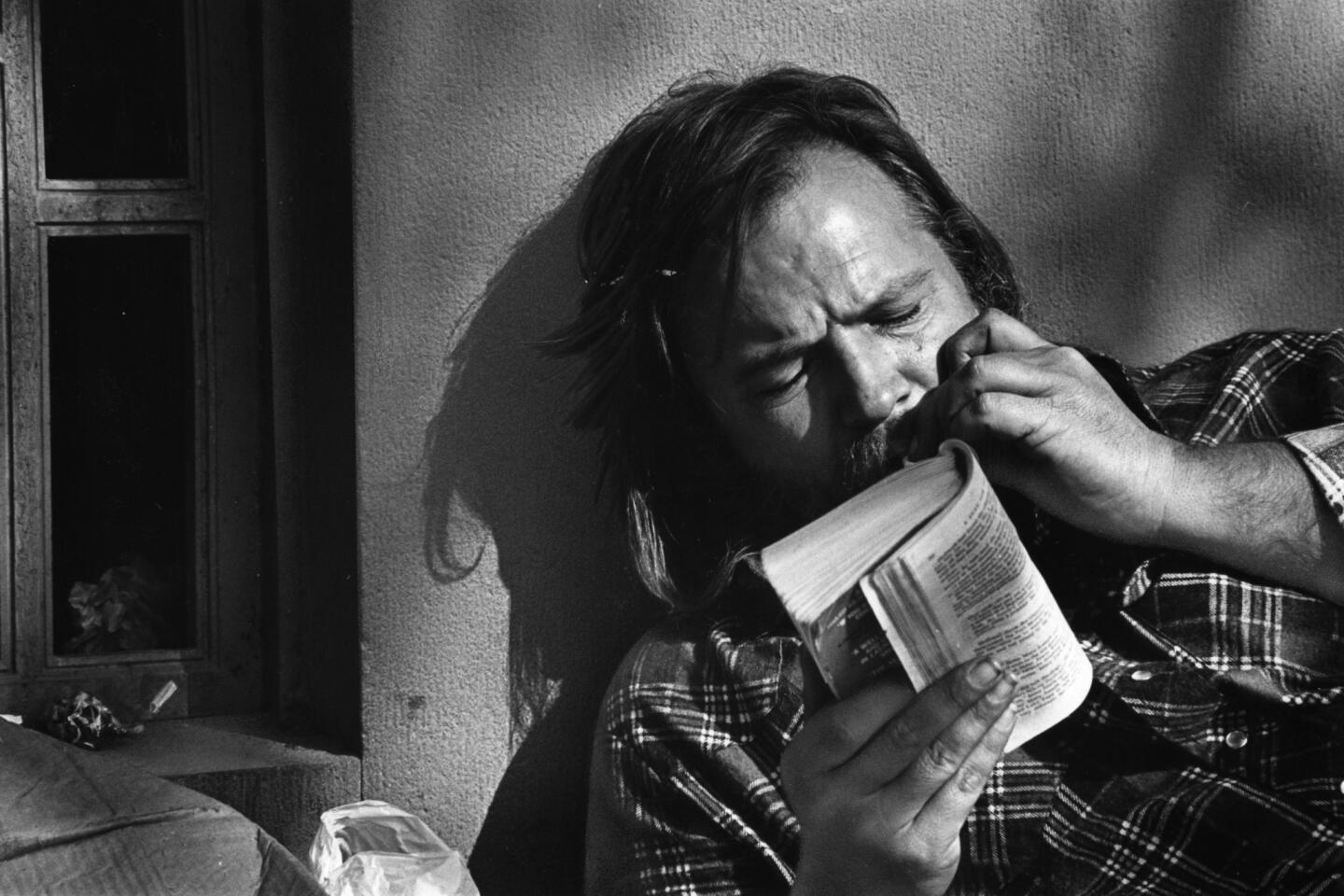

With wry humor, they call themselves “the Troll Family,” after the mysterious, cranky creatures of Scandinavian legend that haunted out-of-the-way places.

They are part of the growing tribe of homeless men and women who dwell in the concrete caves formed by the thousand or so bridges [over] the freeways of Los Angeles. Others camp out in the … shrubbery along the freeway landscape.

No one knows for certain how many of them there may be — freeway trolls come and go without signing registers.

But Norm Brinkmayer, California Department of Transportation maintenance chief for freeways in Los Angeles and Ventura counties, estimates that they may number in the hundreds. California Highway Patrol Capt. Dick Kerri says there is “a Ho Chi Minh Trail” of camps stretching from Ventura to Los Angeles.

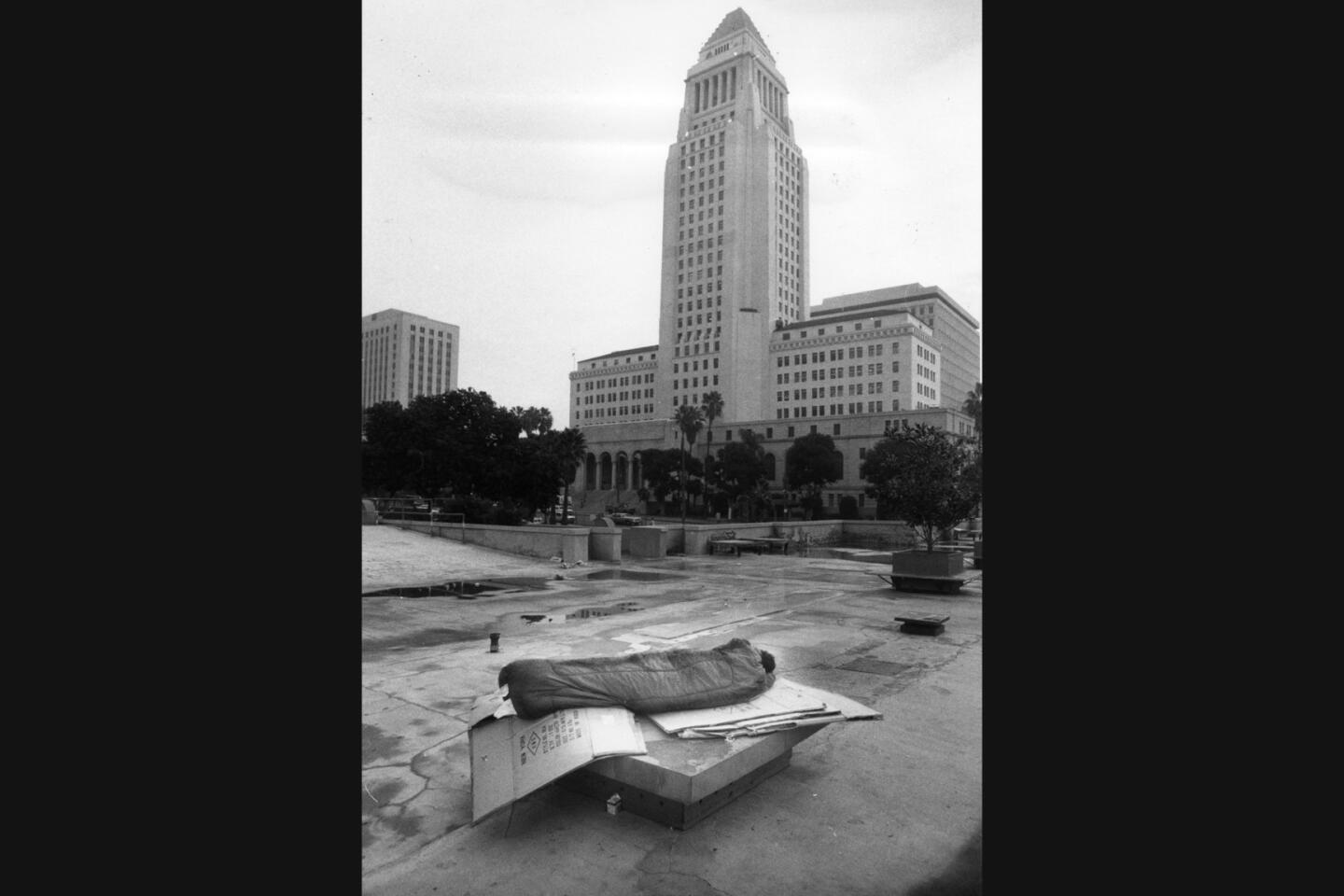

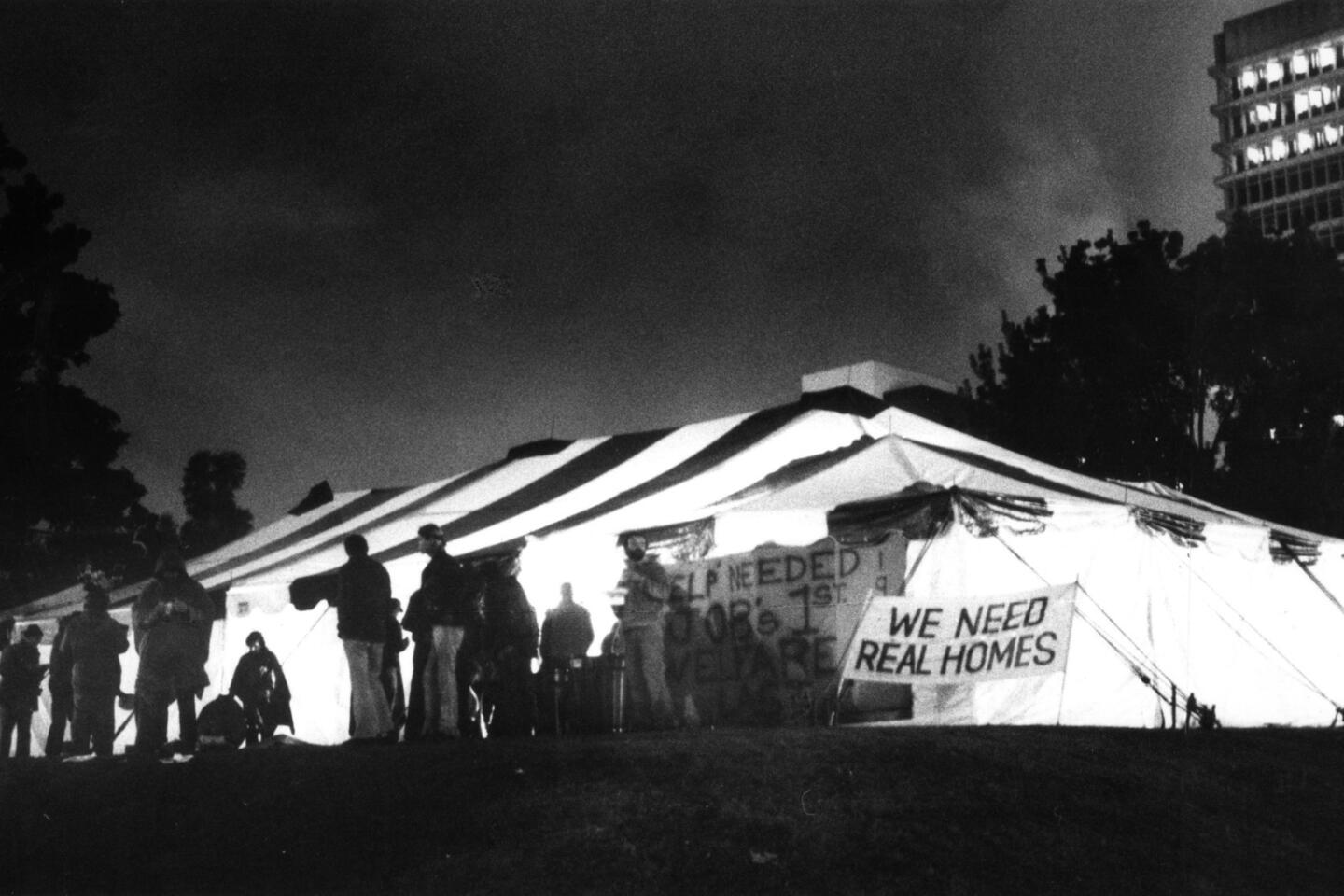

1984: Tent City highlights growing problem

In December 1984, advocates for the homeless opened a temporary shelter downtown at 1st and Spring streets, in the shadow of Los Angeles City Hall.

Nicknamed “Tent City, ” it looks like a battlefield hospital. Cots are lined up, one next to the other, and sleeping bodies squirm under thin blankets. When it rains, drops fall from unseen leaks and deep puddles and mud cover the plastic spread over the grass for flooring.

Inside, about 250 men and women with no address huddle together for the holidays, preferring not to think about eviction scheduled for the day after Christmas. The city eventually let them stay until early January.

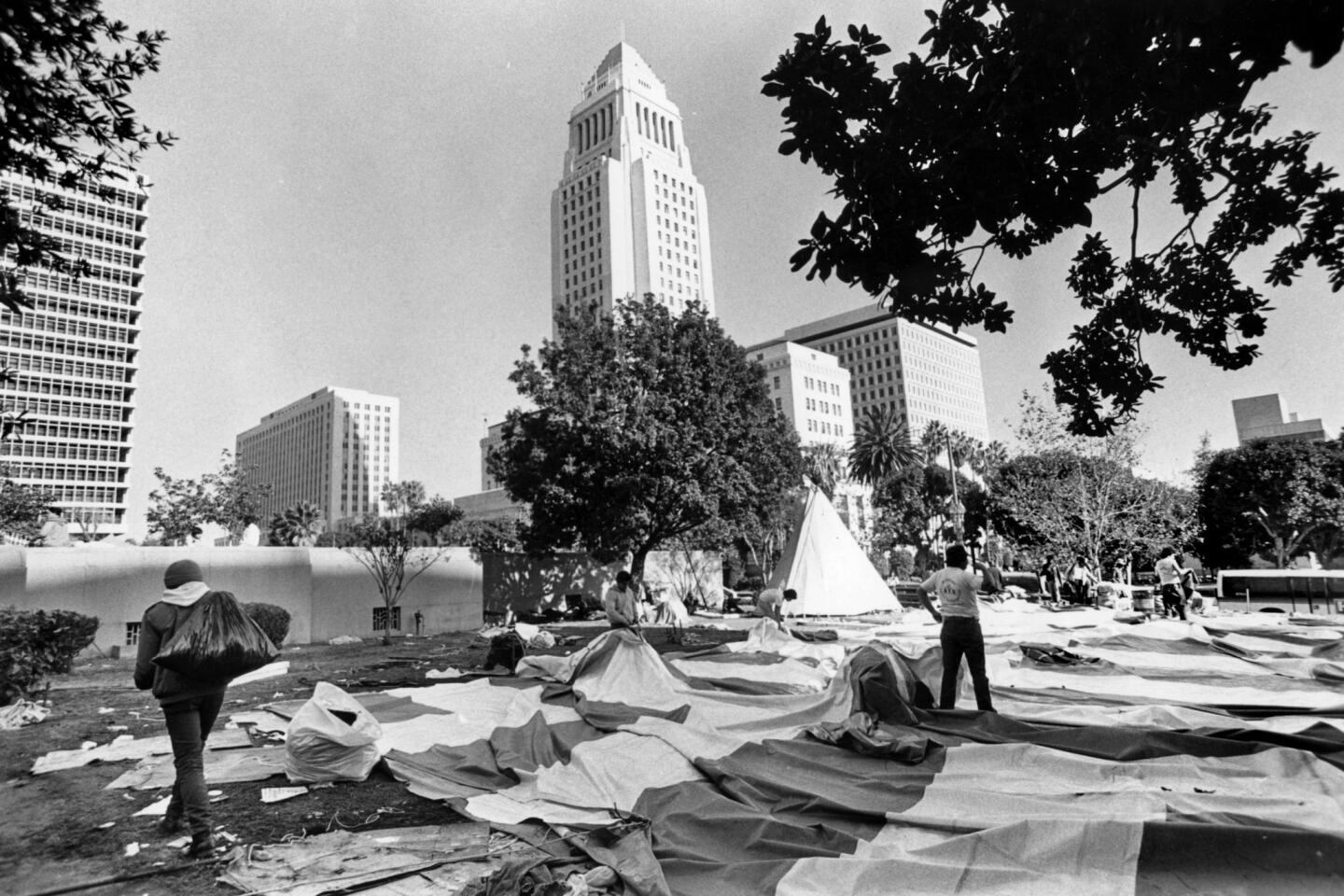

1985: A homeless movement forms

In the spring of 1985, a homeless encampment known as Justiceville sprang up in a children’s playground at 6th Street and Gladys Avenue — a ragtag compilation of plywood, cardboard, tattered blankets, old tires, discarded drapes and about 60 homeless people.

Ted Hayes, who organized the place and gave it its name, said the makeshift dwellings in downtown Los Angeles allow homeless people to take care of themselves, and he has challenged government officials to work with him to come up with a better plan.

But living conditions at the site have become so abysmal that even some advocates for the homeless question whether officials should allow it to exist.

LAPD officers issued eviction orders. Most residents left, but 12, including Hayes, were arrested.

In the early 1990s, Hayes helped form a small urban community of 18 fiberglass domes for the down-and-out.

1987: An unprecedented, symbolic move

Spurred by the deaths of four street people from exposure to near-freezing temperatures, the Los Angeles City Council opened City Hall to serve as temporary housing.

Authorities had come under harsh criticism for failing to provide shelter for homeless residents during the cold spell, which … reached its low point when the temperature at the Civic Center dipped to 36 degrees.

1987: An ‘urban campground’ rises

As the homeless situation got more dire, the city took some dramatic action.

As police continued to force people off skid row’s streets and sidewalks, officials signed an emergency agreement for a temporary “urban campground” for 600 transients on 12 acres of vacant land near the Los Angeles River.

It ended up serving many more homeless people before closing months later.

It was ugly to begin with, a flat stretch of land flanking the river, fenced and then filled up with trailers, canopies, hundreds of cots and tents. Then came the people, 2,600 in all, who said they had no other place to go.

It is still ugly as it ends, a grim, dusty refuge for 236 people who say they still will have no other place to go when the camp is shut down.

The city of Los Angeles’ urban campground for the homeless has been, as Maj. William Mulch of the Salvation Army put it, “a desperate attempt to help very desperate people.”

No one calls the attempt a success — not the city, the Salvation Army or advocates for the homeless.

1991: A changing homeless population

At some agencies, especially at the Weingart Center, the homeless population divides into thirds. The categories seem callous to some, realistic to others.

— “Have-Nots” are the upper third — without jobs, without homes, but without other problems. They can be helped quickly.

— “Cannots” are disabled by drugs, alcohol or mental illness. They can respond to treatment and may benefit from help.

— “Will Nots” are the bottom third, the sidewalk campers who will not work, the derelicts and deranged who will not seek shelter. They, say some, cannot be helped.

Sociologists, educators, economists and psychologists know that yesterday’s homeless were down-and-outs, beggars and vagrants, lazy bums and the romantic hobos. The vast majority were white, elderly, ill-educated, alcoholic males.

Today’s homeless are a full slice of society and include college graduates, single-parent families with children, Vietnam veterans, professionals, businessmen, former politicians, ex-crack cocaine addicts and teenage runaways.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.