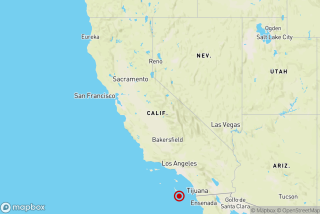

Ventura could be hit by tsunami in hypothetical 7.7 earthquake, study says

An earthquake along the California coast could pose a greater tsunami threat to the Ventura area than previously understood, according to a new study published Tuesday by UC Riverside and U.S. Geological Survey scientists.

Published in the journal Geophysical Research Letters, a publication of the American Geophysical Union, the study found that tsunami floodwaters could reach points in the Ventura vicinity beyond the area currently marked in California’s official tsunami inundation map. Tsunami wave heights could approach as high as 20 feet in the Ventura Harbor and Channel Islands Beach area near Oxnard.

A California Geological Survey official said the agency will study the report. The agency is in the midst of creating a second edition of tsunami inundation maps after publishing the first version about six years ago.

The latest study comes amid new focus on the earthquake faults that stretch deep under the earth in the Santa Barbara and Ventura areas. Previously, some seismic experts thought that faults in this area posed only a moderate threat. But research in recent years suggests that they are connected in a way that could cause a magnitude-7.7 to 8.1 earthquake.

The latest study focuses on a hypothetical scenario in which a magnitude-7.7 earthquake begins nine miles under the Earth’s surface, under the mountains northeast of Santa Barbara.

The earthquake starts on a deep fault – the Lower Red Mountain fault – then moves to the shallower Pitas Point fault under the Pacific Ocean. The earthquake thrusts up the earth north of the fault, lifting up the seafloor permanently and creating a tsunami.

Tsunami waves then spread northward and southward. Santa Barbara itself is largely protected from tsunami by coastal bluffs, but parts of the Ventura and Oxnard areas are particularly at risk -- especially in neighborhoods around the ports at sea level.

“Ventura and Oxnard have lower-lying topography. That region is flatter than other regions around it,” said Kenny Ryan, the lead author of the study and a geophysics graduate student at UC Riverside. “It’s kind of a bad place to have a tsunami propagate into, because a tsunami can propagate into lower-lying lands easier than they can steeper ones.”

The authors of the study emphasized the report’s limitations. It’s only one model of where the tsunami floodwaters would actually go, and there’s no guarantee of destruction if you’re on the wrong side of the line, and no guarantee of safety if you’re on the inland side of the line.

“The real idea from this paper is to start a discussion on doing a more comprehensive analysis of this region,” Ryan said.

Studying how far tsunami waves could travel inland in California is a fairly new subject in the state. It was only about six years ago that the state published maps of areas that could be flooded by tsunami.

Tim McCrink, supervising engineering geologist with the California Geological Survey, said his agency will be studying this paper to see how it might fit in with statewide revisions to the tsunami flood zone maps.

“We haven’t had a chance to look at it to evaluate its probability to tell people intelligently what it means to them,” McCrink said. “It takes a little while to digest it and incorporate it into the policy framework.”

The study includes a map showing areas outside of the state’s tsunami zone that could be at risk of tsunami floodwaters. Some of the new area now labeled at risk appears to be sparsely populated farmland. Other areas are close to the state’s existing tsunami line.

Such a magnitude-7.7 earthquake in the Santa Barbara-Ventura County area would be a rare, devastating temblor for California. There have only been a handful such earthquakes that big to strike since California became a state: the magnitude-7.9 earthquake on the southern San Andreas fault in 1857, a 7.8 temblor in the Imperial Valley in 1892, and the great San Francisco earthquake of 1906, also a 7.8.

Given how the devastating magnitude-9.0 earthquake and tsunami was to Japan in 2011 – and how surprising it was to scientists – it is important to consider how to prepare for rare but possible earthquakes, said study coauthor David Oglesby, geophysics professor at UC Riverside.

“I think it’s worth investigating,” he said. “Certainly, you can’t rule this event out … We wouldn’t simulate it if it wasn’t plausible.”

The most surprising thing about the study, Oglesby said, was how the tsunami wave initially moved south from the fault and then turned sharply east toward Ventura.

The main reason for that is that the western part of the tsunami strikes deeper water first, and begins moving faster than the tsunami’s eastern flank.

Like a rowboat where an oar on one side starts moving faster, the entire tsunami alters course, and heads straight toward Ventura.

The study was coauthored by Eric Geist, a U.S. Geological Survey tsunami modeler, and Michael Barall, an expert in the development of fault modeling software, in addition to Ryan and Oglesby. The report was funded by the Southern California Earthquake Center, which receives money from the U.S. Geological Survey and the National Science Foundation.

Follow me on Twitter: @ronlin

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.