A dangerous opioid is killing people in California. It’s starting to show up in cocaine and meth

Fentanyl, a potent opioid already responsible for thousands of deaths nationwide, is increasingly showing up in drugs like cocaine and methamphetamine in California, officials say.

The white powder, a lethal substance 50 times stronger than heroin, is sometimes mixed into other opioids to produce a stronger high. Now its presence in non-opioids has public health experts worried that California may be staring down a new dimension of the deadly epidemic.

Officials suspect that three men who died in downtown Los Angeles late last month had snorted cocaine laced with fentanyl, an incident that has further galvanized fentanyl fears.

“We don’t know whether this is an anomaly, or whether it’s a bellwether of something that’s about to hit,” said UCLA professor Steve Shoptaw, who studies substance abuse.

Although California has avoided the worst of the opioid epidemic, the drug market here is dominated by stimulants, he said — the very drugs that have just started to be mixed with fentanyl.

Indeed, fentanyl deaths in California tripled between 2016 and 2017, according to the state health department.

Fentanyl, which can kill even in small doses, is dangerous for experienced opioid users, and even more so for people with no tolerance for opioids. Experts say they don’t know whether dealers are purposely or accidentally tainting drugs with fentanyl, but that it’s a concern regardless.

“We need to think of fentanyl being used with a wide range of drugs,” said Jane C. Maxwell, a professor at the University of Texas at Austin who studies substance abuse. “We’re so concerned about heroin and fentanyl, people aren’t really looking at other uses of fentanyl and other problems that might occur.”

About 11:30 p.m. on April 25, Maynor Garcia’s phone buzzed with a text from his older brother, Gabriel Dirzo.

Dirzo wanted to know whether Garcia would host a birthday barbecue for him the following month.

“Yeah bro no problem,” Garcia texted back.

The two had hung out the day before with Garcia’s young daughters and vowed to spend more time together.

Hours later, Dirzo was found dead in his apartment in downtown Los Angeles, along with two other men. Police identified them as Gilbert Valenzuela Jr., 41, of Los Angeles and Robert Ramirez, 36, of Alhambra.

That night, the men had been drinking and eventually began doing what they believed was cocaine, according to reports from the L.A. County Department of Medical Examiner-Coroner.

Officials suspect the men died because the cocaine was actually fentanyl, or was cocaine laced with fentanyl, said Dr. Gary Tsai, medical director of the county health department’s substance abuse prevention and control division.

“Cocaine, while it can be life-threatening, generally doesn’t result in instantaneous overdose deaths like that,” Tsai said.

“Cocaine, while it can be life-threatening, generally doesn’t result in instantaneous overdose deaths like that.”

— Dr. Gary Tsai

Toxicology tests that provide an exact cause of death could take up to two months, said Ed Winter, a spokesman for the coroner’s office.

Fentanyl has been prescribed as a painkiller for cancer patients since the 1960s. But an illicit version is being manufactured and can be easily mixed with other drugs without being noticed.

Several people in San Francisco have recently died from consuming fentanyl with methamphetamine, counterfeit Xanax or crack cocaine. There have been reports elsewhere of fentanyl in the rave drug MDMA.

“We aren’t seeing the volume or the impact that … is happening on the East Coast, but we know that could change,” said Rachael Kagan, spokeswoman for San Francisco’s Department of Public Health. “We’re really on high alert.”

California has the seventh lowest drug-overdose death rate in the nation, in part because of the type of heroin sold here, experts say.

Black tar heroin is sold west of the Mississippi, whereas the kind most commonly sold in the East is a white powder. Black tar heroin is harder to mix with fentanyl and therefore less likely to cause overdoses and deaths, experts say, but that advantage could fade as fentanyl shows up in other substances.

In the last year in Southern California and the Central Coast, federal agents have repeatedly made seizures of cocaine with fentanyl, methamphetamine with fentanyl and ketamine with fentanyl, according to Timothy Massino, a spokesman for the Drug Enforcement Administration in Los Angeles.

“This is a fairly new phenomenon in this area,” he said.

Some experts believe dealers are adding fentanyl to their product to give it an edge or are trying to pass fentanyl off as another drug because it’s cheaper to manufacture.

Regardless, the presence of fentanyl in cocaine and methamphetamines could expose a new group of people to opioids. Americans are much more likely to have tried cocaine or meth — about 16% and 7% have in their lifetime, respectively — than heroin, which about 2% have tried, according to data from the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

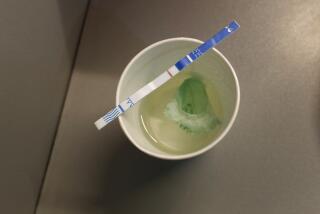

Given the concerns about fentanyl, the California public health department is providing needle exchanges with test strips that people can use to test their drugs for fentanyl.

At Venice Family Clinic Common Ground, which offers a needle exchange, users have reported that they’ve detected fentanyl in meth and cocaine, director Arron Barba said. People can’t tell what’s in the drugs they’re buying, and it’s clear fentanyl is increasingly part of the equation, she said.

“There’s no quality control, and there’s no government to step in and say you can’t do that,” Barba said. “I think it’s only going to get worse.”

Tsai, of the county health department, said Saturday that the county will send out an alert soon about rising fentanyl deaths. In Los Angeles County, fentanyl overdose numbers increased from about 45 in 2015 to more than 60 in 2016 and were even higher in 2017, he said, without specifying a figure because it is preliminary.

In general, though, Tsai and other experts said that while fentanyl is a real, growing threat, it’s not at the top of California’s health problems.

In fact, some said they felt the danger of fentanyl contamination had been exaggerated. The increase in reported fentanyl deaths could be in part due to increased testing for fentanyl in recent years, they say. Plus, toxicology reports that find fentanyl in someone’s blood doesn’t mean that the person wasn’t aware they took the drug, they said.

“Fentanyl is a drug of choice for some people and it has been for years,” said Paul Harkin, harm reduction programs manager at Glide, a clinic in the Tenderloin neighborhood in San Francisco.

Others said that people might purposely mix drugs, or might take fentanyl after taking an upper like methamphetamine to help them go to sleep.

Dr. Daniel Ciccarone, a UC San Francisco professor who studies heroin usage, said he thinks the trend of fentanyl showing up in stimulants is just accidental contamination — “the first batch of coke to go in the blender after the heroin was in the blender.”

Garcia, thinking about his brother’s death, said he welcomed more information about fentanyl.

“I wish there could be something like awareness, like ‘Hey, if you’re going to party in downtown L.A., be careful if you get offered any type of drugs,’ ” said Garcia, 27. “I’m not encouraging people to do cocaine, but people do, and then those people that do it ... need to understand that it could be lethal.”

soumya.karlamangla@latimes.com

Twitter: @skarlamangla

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.