Atop Mt. Wilson, retired engineers keep alive astronomy’s ‘Sistine Chapel’

Dressed in parkas and knit caps, the three volunteers lug crates of power tools and spooled wire into the gleaming mountaintop edifice that some have called astronomy’s “Sistine Chapel” and immediately start tinkering.

In 1904, workers installed the first telescope at the still uncompleted Mt. Wilson Observatory. For much of the 20th century, astronomers with names like Hale and Hubble used it and the new telescopes it sprouted — the 100-inch reflector and three solar telescopes followed the initial 60-incher — as a figurative launch pad for exploration that changed our understanding of the cosmos.

Gradually, though, financial support waned along with the observatory’s cutting-edge status, and for the last 20 years its telescopes, still impressive by any standard, rely on the kind attention of a small volunteer team of retired space industry electrical engineers, most now in their 70s and 80s.

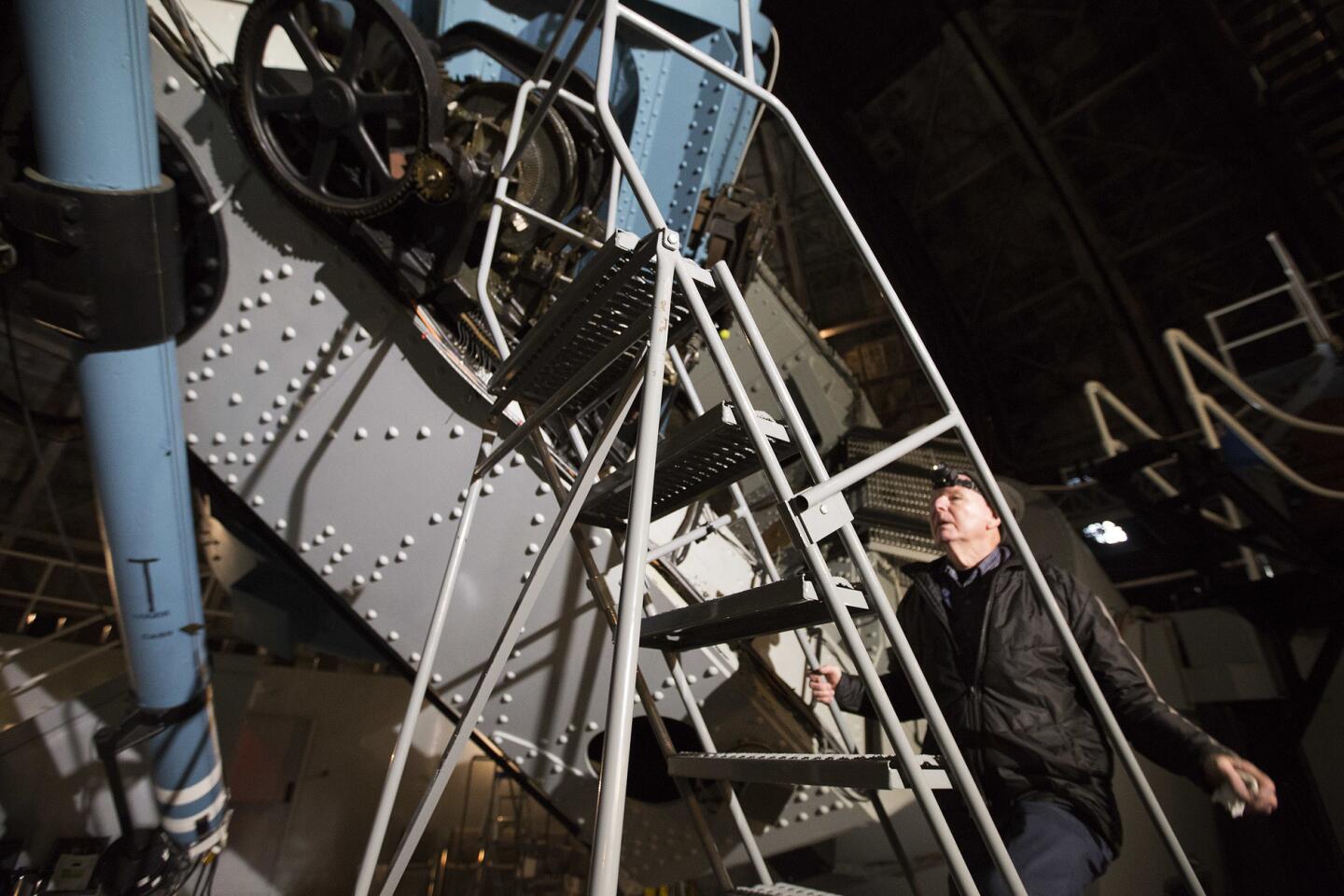

So it is that on a morning when parts of the San Gabriels are topped with snow, Kenneth Evans is on a ladder, his head lamp fixed on a new sensor switch for a 100-inch reflecting telescope that dominated the world of astronomy for more than three decades.

Nearby, William Leflang and Gale Gant test the wiring of a control console.

Dusting off his hands, Evans tells Leflang to “give it some power.”

He pivots to eyeball the sensor, which will improve the scope’s ability to track the movement of celestial objects, and with a grand wave of his grease-covered hands, says, “Works great.”

Our volunteer engineers are heroes. They are keeping it alive.

— Thomas Meneghini, Mt. Wilson Institute executive director

Satisfied smiles break out on the faces of men who seem confident that they were born to fix things.

The volunteers took up their cause in the late 1990s after the Carnegie Institution for Science, whose namesake had invested the initial funds for construction, transferred ownership of the Mt. Wilson Observatory to the nonprofit Mt. Wilson Institute.

Now, they shoulder much of the responsibility for keeping the observatory’s cluster of vintage telescopes from deteriorating into non-functioning museum pieces.

Other volunteers include John Harrigan, a former power distribution expert at the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power; Richard Johnston, an information technology consultant, and his son, Eric Johnston, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Bristol’s Center for Quantum Photonics. Taking on problems one weekend work party at a time, the team has solved hundreds of pressing issues at the 40-acre observatory complex.

They have patched holes in walls, strengthened ceilings and walkways with wooden beams, fixed broken water mains and used steel wool and solvents to scour rust and old axle grease off flywheels and gears at the observatory, which looks much as it did when it was completed in 1917.

Mt. Wilson aficionados still talk about how Evans and his brother Larry refurbished a 1911 50-horsepower 2-cylinder vertical Fairbanks-Morse Type “RE” engine with brass plumbing and 22,000 pounds of machinery so that it could be used in demonstrations.

Now they’re laboring to improve the giant reflector’s potential as an educational tool and tourist draw.

But money for maintaining the observatory remains tight, the institute says, and the fate of the reflector, hailed as the mightiest instrument in astronomy when it was built, remains uncertain.

For Thomas Meneghini, the institute’s executive director, the facility’s dual nature conjures a peculiar charm: rooms where Albert Einstein once bunked bunched around picnic grounds, a museum, hiking trails and vista points that offer views from Pasadena, directly below, out across Southern California.

“But raising funds has been a challenge. That’s why our volunteer engineers are heroes. They are keeping it alive. Without them and other supporters, these magnificent instruments would just be cold hunks of steel and glass.”

A 150-foot-tall solar facility at Mt. Wilson has already deteriorated to the point that it can be used only for school programs and public demonstrations. That instrument’s 1970s-era computer system is a shambles. Its magnetograph — an instrument allowing detailed observations of the sun’s magnetic fields — was shut down in 2013, a year after its tower received a new coat of paint funded with a $1.5-million federal grant.

A separate solar telescope installed in 1904 to make photographic images of the wavelengths of the sun’s light has come to be known as “Leflang’s baby.” That’s because he maintains that instrument, which is used only two weeks a year for educational purposes.

Mt. Wilson’s biggest draw remains the 100-inch reflector, which reigned supreme until completion of Caltech’s 200-inch telescope on Mt. Palomar in San Diego County after World War II.

While Los Angeles slept, astronomer Edwin Hubble and others used the reflector to discover billions of galaxies where none were known before, most of them speeding away from each other in all directions. These observations led to the Big Bang theory, which suggests the universe began in a single explosive moment.

Keeping it in reliable shape, however, has been a work in progress since 1985, when the Carnegie Institution for Science put it in mothballs due to light pollution in the Los Angeles Basin and a commitment to expand its Las Campanas Observatory in Chile, which was more suitable for focusing on distant faint objects.

The telescope was reopened in 1994, nine years after Carnegie officials transferred ownership to the institute.

But it needs upgrades to continue operating.

And so the unusual fraternity gathers, trash-talking one another in terms that perhaps only those who recite antique gas engine minutiae like baseball stats can appreciate.

“There’s a lot of epic history in here,” Leflang says, proceeding gingerly past colossal marvels of World War I-era engineering and astrophysics.

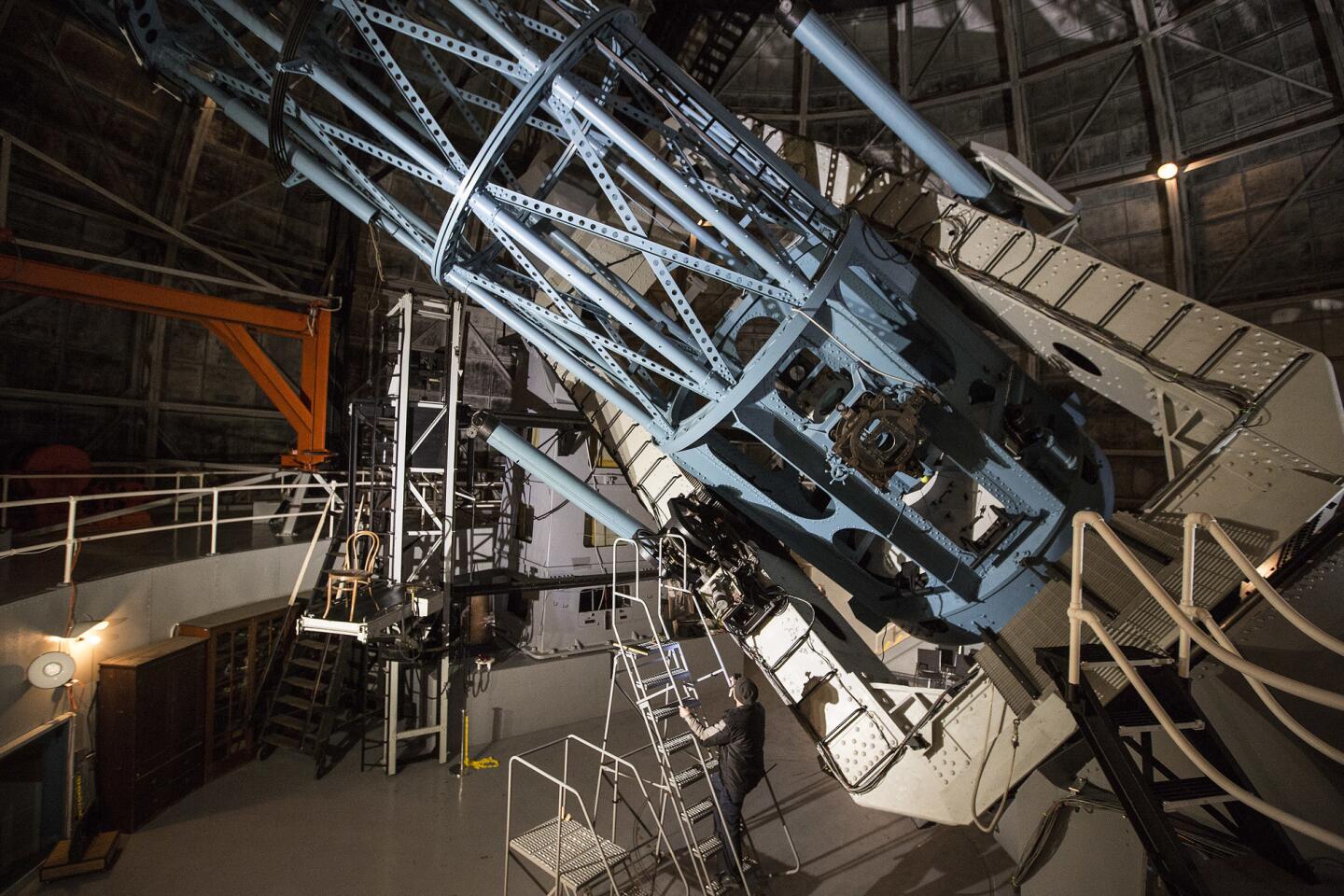

The 87-ton scope has 2,000 moving parts including a cast-iron worm gear 18 feet in diameter. Steel cables as thick as mooring ropes attached to a crane used to service its 9,500-pound primary mirror. A 450-ton dome rotates overhead on trolley tracks.

Framed photographs of Hubble, George Ellery Hale and other pioneer astronomers are displayed on walls and scaffolding studded with rivets, and in the drawers of a wood filing cabinet are hundreds of original blueprints of the facility dated Jan. 17, 1917.

It takes the team about an hour to complete the modification, which they accomplished without altering the telescope’s basic design or optics.

“Some folks refer to this scope as the grand dame of astronomy,” Gant says with a boyish grin. “We call it a complex beast.”

After a 10-minute breather, the team members give one another approving nods, load their pickups, and head back down the mountain.

ALSO

California’s busiest rapid transit rail system may designate itself a ‘sanctuary’

Here’s what the president of MIT thinks of the Trump administration’s early moves

Oroville Dam’s emergency spillway used for the first time amid rising waters

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.