Massive warehouse plan has Moreno Valley divided over jobs, environment

In the last few years, the warehouses have been popping up swiftly in Moreno Valley.

On the east side of town, the German grocer Aldi is building an 825,000-square-foot distribution facility. A 1.6-million-square-foot distribution facility for the footwear company Deckers Outdoor and other businesses is under construction across town. An Amazon fulfillment center totaling 1.25 million square feet opened last year.

But in the building boom that has seen a surge of warehouse construction in the Inland Empire since the recession, Iddo Benzeevi’s proposed World Logistics Center dwarfs all other projects.

If his plan is approved, the developer could build more than 40 million square feet of warehouse space — enough to fit almost 700 football fields — on the eastern edge of Moreno Valley, on a vast stretch of Riverside County bounded by tract homes on one side and rugged hills on the other.

Benzeevi and the project’s supporters say it would bring jobs to a city that has struggled with poverty, unemployment and a foreclosure crisis that devastated neighborhoods.

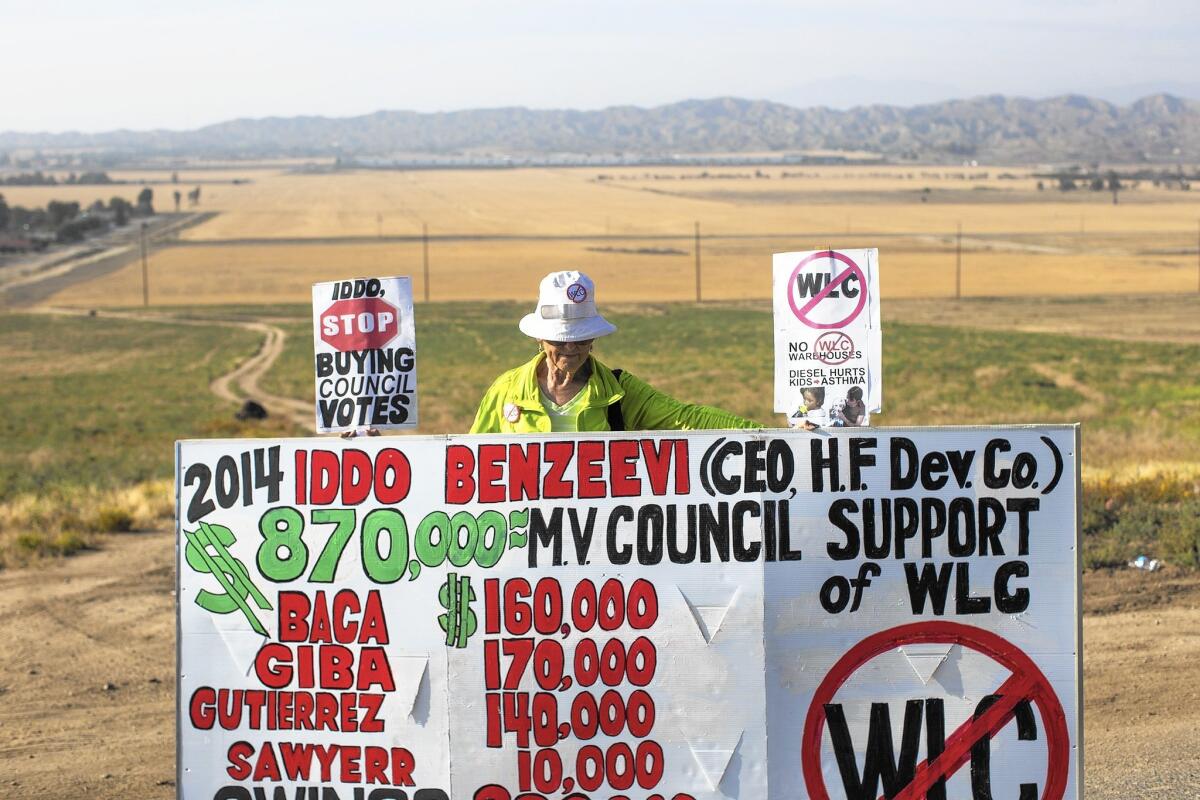

Critics are wary of the project’s scale, of the low-wage jobs and environmental problems they say go hand-in-hand with warehouses, and of Benzeevi, who, with his company, has spent hundreds of thousands of dollars to influence local elections in the city where, as one councilman put it, “$5,000 is a lot of money.”

The center’s fate will probably be decided later this year by the Moreno Valley City Council, but it is also being closely watched by residents and regional leaders, many of whom are concerned about the area’s increasing transformation into a hub of warehouses and distribution centers built to accommodate the growing digital and global economy.

“It seems as if these warehouses are locking us in,” said longtime resident Donovan Saadiq.

Kathleen Dale, who has lived in Moreno Valley most of her life and is part of a group of residents trying to stop the project, says the city of about 200,000 residents is already coping with large numbers of trucks going to and from warehouses.

On a recent weekday, she looked across the expansive site that World Logistics Center would occupy toward the Skechers footwear distribution facility developed by Benzeevi’s company in 2011. The warehouse, one of the largest in the country when it opened, is 1.8 million square feet and a half-mile long.

“They’re just talking about plunking another 20 of those in cookie-cutter form as far as you can see,” Dale said.

Since its incorporation in the 1980s, when Moreno Valley grew quickly to accommodate families buying homes they couldn’t afford farther west, the city has twice been hit hard by boom-and-bust cycles of residential development. After the most recent housing bust, abandoned homes dotted neighborhoods for years. Many residents who had found decent-paying jobs in construction were left scrambling.

Today the city continues to struggle, with a per capita income nearly 40% below the state average and nearly a fifth of the population living below the poverty level, according to census data. For those who do have jobs, the average commute to work is 34 minutes.

County Supervisor Marion Ashley said the city was stung by recent news reports that listed it as one of the worst cities in the nation for jobs.

Moreno Valley and the Inland Empire are “still recovering from the great recession,” he said. “We’re still hurting out here.”

Four years ago, city officials zeroed in on the lack of local jobs as Moreno Valley’s foremost problem and began aggressively pursuing logistics development.

On the eastern edge of town, officials pegged thousands of acres of undeveloped land owned by Benzeevi’s company as ideal for logistics. In the 1980s, Benzeevi had proposed an aeronautics facility in that part of town. He later pitched a massive residential project, also on the city’s east side. Neither project got off the ground.

Benzeevi said his latest project, which has been endorsed by the city’s planning staff, would bring 20,000 jobs to a city where people have been “waiting, literally begging for jobs to come.”

Though Benzeevi has been criticized for inflating the number of jobs that would ultimately be available at the Skechers facility, logistics jobs are helping propel the region out of an unemployment crisis that reached rates of more than 14% five years ago. Last year, about 20% of all jobs created in the Inland Empire were in the logistics industry. In May, regional unemployment was at 6.4%, lower than Los Angeles County’s 7.3% rate.

“The industry has been a boon to commercial real estate developers and landowners, and it has increased employment in the region,” said Riverside Mayor Rusty Bailey, who is keeping a close eye on the project. But, he added, he’s still learning about whether “those jobs allow someone to support a family, buy a home and invest in their children’s education.”

John Husing, chief economist for the Inland Empire Economic Partnership, which includes local cities and businesses (including Benzeevi’s Highland Fairview), said the center’s 40 million square feet amounts to about two years’ worth of new logistics space occupied by businesses in the Inland Empire.

“Which would you rather have: haphazard, one-at-a-time development adding up to 40 million square feet, or master plan the whole thing at the same time where you can make sure all of the amenities are there?” he said.

In a community that is already coping with some of the worst air quality in the nation, however, critics say the project would impose a heavy environmental burden.

The center would likely draw about 14,000 trucks on daily trips into the city, according to the project’s environmental impact report. Emissions of multiple pollutants would exceed thresholds set by the South Coast Air Quality Management District and would have to be mitigated.

The environmental impact report and Benzeevi say a requirement to use newer trucks would eliminate the health impacts of diesel exhaust.

But the California Air Resources Board recently sent the city a letter calling the report, which was paid for by Highland Fairview, “legally inadequate.”

The city also has received letters in recent days from a host of objectors to the report, including the American Lung Assn. in California, the South Coast Air Quality Management District, the California Department of Fish and Wildlife, various environmental groups and county transportation officials who say it failed to address or mitigate the project’s “significant traffic impacts.”

“There’s a lot of red flags being thrown from all over the state,” said Adrian Martinez, staff attorney for the environmental law nonprofit Earthjustice, which has been monitoring the project.

This month, hundreds of residents packed a city recreation center for a planning commission hearing on the project. Many were opposed to it, but there also was a large number of working-class men and women who carried signs that read “Yes to Jobs.”

Some such as Rafael Brugueras, who has lived in Moreno Valley for 22 years, learned about the project when someone knocked on their door and invited them to a small gathering with Benzeevi.

It’s time, Brugueras said, “to once again give the city of Moreno Valley an opportunity to create jobs.”

RosaMaria Martinez, 60, said she used to own a day-care business in town and often served parents who left their children at 6 a.m. and didn’t return until 8:30 p.m.

“We need jobs,” she said.

As the city moves toward a decision, Benzeevi continues trying to explain to residents his vision for World Logistics Center.

He says his latest project could make Moreno Valley recognizable around the world.

He talks of building an iconic structure — possibly a large bridge in the shape of a white triangle that would extend above the freeway on an exit leading to World Logistics Center — to ensure that visitors know they are entering “the No. 1 logistics center in the United States.”

The bridge would be paid for by local fees, including those imposed on developers for increased traffic created by a project, he said.

“It’s an icon,” he said. “It’s just like the Golden Gate symbolizes San Francisco and the Eiffel Tower symbolizes Paris.”

paloma.esquivel@latimes.com

Twitter: @palomaesquivel