For college textbooks, newer -- and pricier -- isn’t always better

At Cal State Stanislaus, computer science faculty maintain a small library of textbooks so students don’t have to buy them.

Chico State history professor Susan Green invites former students to sell their used textbooks to new arrivals on the first day of class.

And when CSUN professor Lynn Gordon informed her elementary education class that she’d spent more than $500 out of her own pocket on textbooks to lend to every student, cheers erupted.

As the price of new college textbooks continues to rise, many students returning to class this fall are finding sympathy — and relief — from faculty.

Between 2002 and 2012, prices for new textbooks rose 82%, while tuition and fees increased about 89% during that period, and overall consumer prices grew 28%, according to a 2013 report by the U.S. Government Accountability Office.

The report found that while students often turn to used texts and digital versions, spiraling prices for new print editions are forcing up costs for even those alternatives.

Meanwhile, the GAO report found that there’s been little change in the way most faculty select textbooks: they are most concerned with the usefulness of the information and usually order the latest, most expensive edition with little thought to the cost.

Faculty at many colleges and universities, however, said they are becoming more aware that many students can’t afford to buy all of the books they’re assigned and that it could be a barrier to completing their education.

“The goal in every professor’s mind is getting the best material and the best book to provide a quality education,” said Samuel Dunietz, a research and policy analyst for the American Assn. of University Professors. “But I think they are becoming more mindful that it’s a potential obstacle to getting a quality education if a student doesn’t have the money and they just may not buy the books.”

Lisa Parker transferred from Butte College to Cal State Chico and said she was surprised by the different attitude when it came to assigned reading.

“A lot of professors at Butte were using older books and seemed to be more aware of the different demographics of students they were trying to educate,” said Parker, 26, a social work major and single mother. “They were more lenient when it came to price and edition, where at the university I found a lot of difficulty being able to afford $200 newer-edition books that changed from semester to semester.”

But Parker also found instructors such as Green, who provides contact information for students who took her classes in previous semesters and are willing to sell their books. Parker is planning to sell her Chicano studies book.

Green said she has kept her assigned reading — retail price about $82 — pretty consistent across semesters and that her books are stocked at the independent bookstore downtown. There, students said they get a better buy-back rate than they do at the campus bookstore.

At Cal State Stanislaus, computer science professor John Sarraille said he was surprised that some assigned texts cost $160-plus. Many students this semester are asking whether they can use older editions, he said. The computer science and math departments have created small libraries where students can check out current copies that include information they may not find in older editions.

Sarraille said most professors are aware that many students at the Turlock campus are struggling to make ends meet.

“The lending libraries are popular, and the students are grateful and really appreciate it,” Sarraille said.

Also at Stanislaus, the six professors who teach business ethics decided to use materials freely available on the Internet for next year’s classes rather than pricey textbooks. The plan will potentially benefit 800 to 1,000 students.

Textbook prices, said accounting professor Steven Filling, drove the cooperation among professors. “A lot of faculty knew there was open stuff sitting out there, but it takes a lot of work to go through and evaluate and see if it meets our needs. But when you look at student debt, it’s something we need to do.”

The plan came after many student discussions that centered on “how ethical is it for me to ask the class to pay $135 for a book,” noted Filling, who is chairman of Cal State’s Academic Senate.

Faculty and students at UC Davis, meanwhile, are developing what they call “hyperlibraries” of faculty writings, homework questions, research and other content available online that are then vetted, and, like a Wikipedia page, constantly expanded and adapted to meet specific needs.

The goal is to produce e-textbooks in the chemistry, biology, statistics, math, physics and geology fields — dubbed ChemiWiki, BioWiki, MathWiki, etc. — that eventually will supplant traditional texts, which can cost up to $300 per copy, said UC Davis chemistry professor Delmar Larsen.

A pilot study of the ChemWiki last spring found that students in a general chemistry class who used the online materials would have spent about $125,000 had they bought new textbooks, Larsen said.

The project has spread to Diablo Valley College, Sonoma State University and Howard University in Washington, D.C., among other institutions.

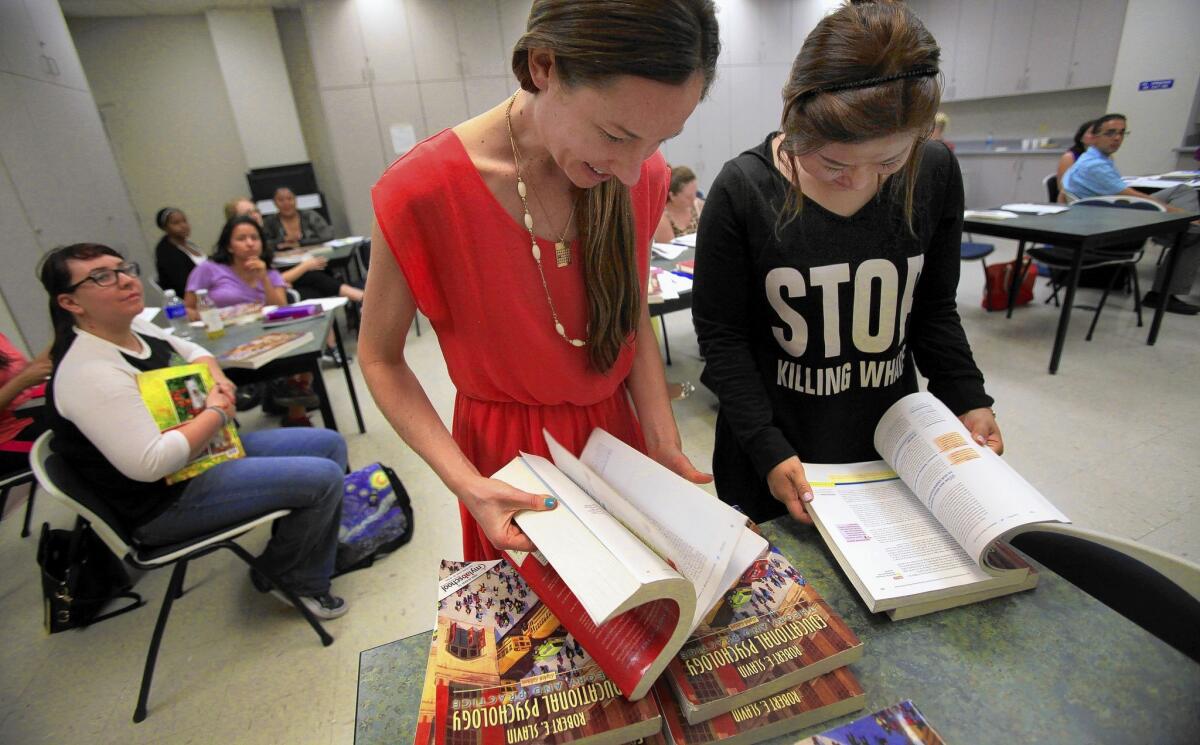

Cal State Northridge professor Gordon may have gone the furthest when she bought 130 used textbooks for three of her teaching credential classes. She bought the books from an online used-book seller for less than $4 each after selecting copies about 10 years behind the current edition.

Students would have had to pay from about $127 to $183 for the latest edition, depending on where they bought the book.

The older editions are still suitable, and she supplements them with more recent handouts on such topics as the new California Common Core curriculum.

“I’m not doing this so that you’ll love me, but, of course, you will,” Gordon told her class recently.

“This is awesome,” said Jason Manzatt, 44, who had gone to the bookstore to look for the texts before class but didn’t buy them. “My books are from $140 to $200 per book and I’m taking six classes. I’ve had professors who allowed you to buy older editions, but never any who bought the books for you.”

carla.rivera@latimes.com

Twitter: @carlariveralat

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.