When LAUSD’s random searches of students end, what’s next for school safety?

In the early 1990s, five students at Belvedere Middle School in East L.A. were killed, recalled then-Principal Victoria Castro, in incidents off campus during a violent period when there were regular student fights, attacks on teachers and tensions throughout the area fueled by the L.A. riots.

By 1993, when two students were killed in shootings at Fairfax and Reseda high schools, Castro was among those who cheered when L.A. Unified began wanding students with metal detectors and allowing random searches.

In 2011, after a shooting at Gardena High School, the district mandated daily searches at every middle and high school.

Now — 26 years after the wanding policy was introduced and amid years of pressure from advocates and student activists to end the practice — leaders of the nation’s second-largest school district have voted to eliminate the policy by July 2020, directing the superintendent to come up with a different plan to keep students safe.

Even during a time of heightened anxiety spurred by mass shootings such as that at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Fla., the stance by the Los Angeles Unified School District on random searches has been unique — of the nation’s 15 largest districts, it’s the only one to require daily random searches, according to a 2018 report by the American Civil Liberties Union.

Many also saw the policy as punitive and a barrier to the social-justice lens that many schools have been adopting.

In a district where the majority of students are nonwhite, critics argued that the search methods aren’t neutral and disproportionately affect black, Latino and Muslim students, potentially embroiling them at an early age in the criminal justice system.

The Los Angeles city attorney recommended last year that the district suspend the searches and conduct an audit to determine whether they are effective and truly random.

The timing of the policy flip is in part a reflection of a changing school board that has faced issues of new leadership, a board member’s money laundering scandal, threats of a financial breakdown, a teachers’ strike, declining enrollment and a constant battle between charter and traditional schools.

It took a while for elimination of random searches to reach the top of the list.

Even former defenders such as Castro came to view the current enforcement as counterproductive and ineffective.

“That’s time away from students, and as noted, students never appreciated it,” said Castro, who became a school board member after leaving Belvedere.

Random searches don’t find guns

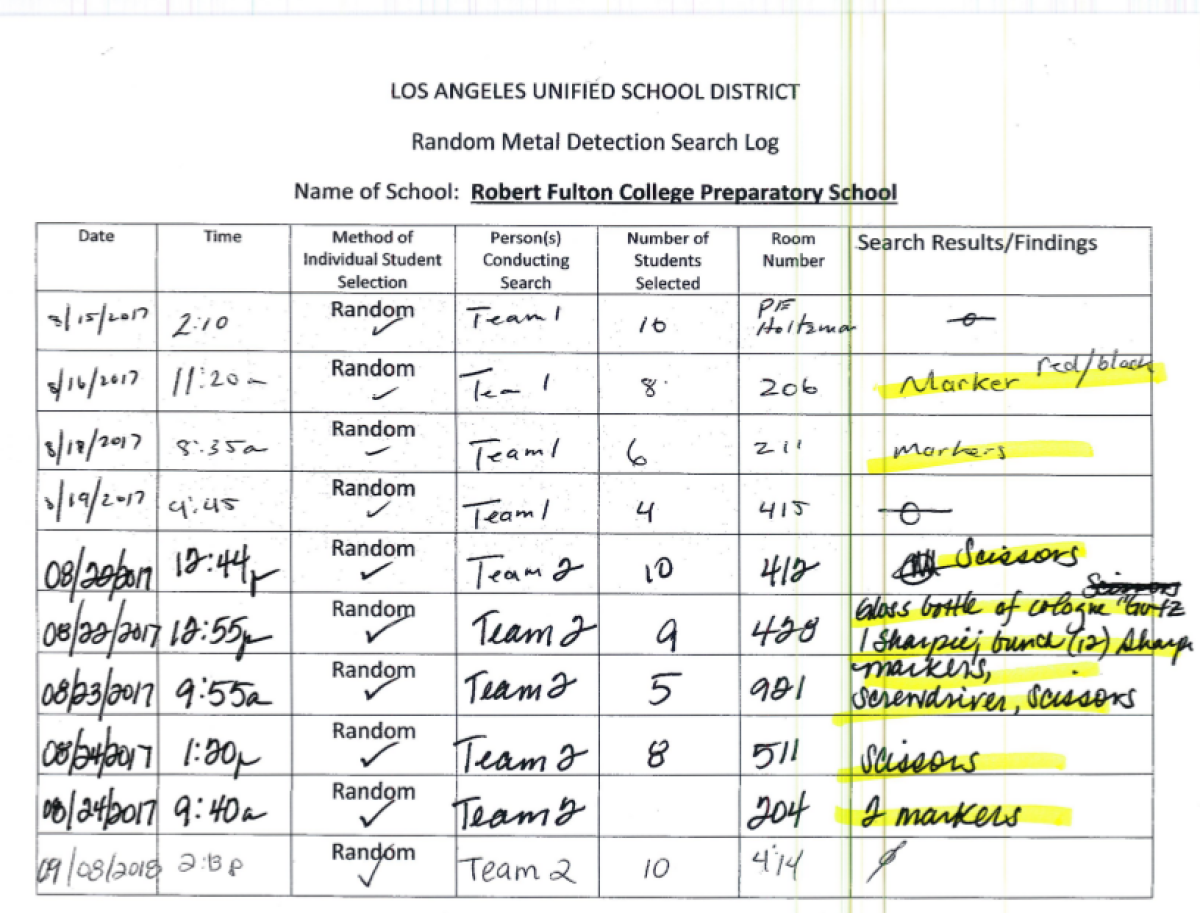

A coalition called Students not Suspects, which includes the ACLU of Southern California, United Teachers Los Angeles and Black Lives Matter, has long said L.A. Unified does not enforce the policy equally and cites the district’s own limited data showing the searches yield more confiscations of contraband, such as markers and body sprays, than guns and knives.

There has been incremental movement in the last year — 14 schools were part of a pilot program to reduce the number of searches, and as a part of January’s strike agreement, 16 schools will be exempt from searches this fall.

A Times analysis of logs from the 2016-17 school year showed that the random searches did occasionally yield knives and pepper spray, but no guns. The district is still analyzing data from schools that participated in the limited search pilot program in 2018-19.

Though schools don’t keep track of who is searched, the fact that the only major district to implement such searches is majority non-white and low-income suggests that these students face surveillance more than their white, wealthier counterparts elsewhere, students and activists say.

The policy’s supporters say the low numbers of weapons seized show the searches are effective.

“It’s the scarecrow effect,” L.A. School Police Assn. President Gil Gamez said during the school board’s recent meeting. Though school administrators, and not police, conduct the searches, campus police step in if a weapon is found.

And in fact, students do bring guns onto campuses, and police do find some of them — just not through random searches. In the 2016-17 school year, police confiscated 18 firearms, according to a report obtained from the district. Often, administrators say, those weapons are found because other students report them.

Whatever new policy the district adopts cannot include increased police presence or randomly picking students in any other form.

Some educators remain unsettled about the threat of violence and unsure about the right direction.

At the Communication & Technology School at Diego Rivera Learning Complex in the Florence-Firestone neighborhood, there was heated debate over whether to submit an application to be exempt from the searches, said Principal Cynthia Gonzalez.

The searches there yield more banned substances — such as cannabis wax and vape pens — than they do weapons, Gonzalez said. An alternate policy should find a way to make sure teachers and students both feel safe and can address current issues in schools, such as substance use.

“Wanding might not be the answer but then what is the answer?” Gonzalez asked. “How is the district going to be proactive about making sure the schools have resources to address the problems that come up?”

‘Like I was a bad person’

Many students plucked out of classes for searches said they feel as though administrators are treating them like criminals, that their learning is disrupted and they are less likely to trust adults on campus.

Recent Dorsey High School graduate Marshe Doss said she was searched 11 times in the last six years.

The first time, in seventh grade, she said, she didn’t know why administrators went to her classroom or why she was made to pull everything out of her backpack. She’s had hand sanitizer and scissors confiscated. “When I first was getting searched, I always felt like I was doing something wrong. Like I was a bad person if I was getting searched,” Doss said.

Her sister is entering sixth grade in the fall, Doss said. She doesn’t want the two of them to share this memory. “I just don’t want my sister to experience that, and I don’t think any 11-year-old should experience that.”

Nadera Powell, an incoming junior at Venice High School, said she and five other students were pulled out of a seventh-grade lecture on Anne Frank to be searched. She stood with her arms spread in a T shape, while a male administrator ran the wand across her. Though neither he nor the wand touched Nadera, she said she felt uncomfortable.

“It felt like I was being violated, but at the time I didn’t really understand what was happening,” said Nadera, 16. “It seemed like it was the right thing to do, to just stand there and let them do what they needed to do so I could go back to class.”

The searches erode the trust between students and adults at schools and interrupt learning time, Nadera said. “It just changes the atmosphere of school, it doesn’t feel like a loving environment. … It feels like a prison,” she said.

What’s next?

Violence in L.A. has decreased significantly since its peak in the 1990s, but hundreds are still killed every year in the county, and those deaths heavily affect schools and students.

School board support to end the searches wasn’t unanimous. George McKenna, Richard Vladovic and Scott Schmerelson — all former school principals — voted against eliminating the policy.

In meetings, McKenna has talked about his time at Washington High in the 1980s, when a student shot off-campus died in his arms.

Activists, though, have lambasted him for his support of searches and wanding, especially as the only black board member.

Because administrators don’t keep track of the race or gender of the students searched, there’s no way to know whether black students are unfairly targeted, McKenna said. “I will accept the criticism. I know it’s a discomfort, I know it’s a distraction. I know it’s not something you look forward to. But I would rather be safe than sorry.”

Castro, the former Belvedere principal, who is now retired, said there should still be some ability for principals to search students in situations, for example, in which there is a campus rumor about a gun or planned retaliation and when shootings spike in the area.

The most recent school shooting in L.A. Unified — which went unmentioned by board members during their recent discussion on wanding — occurred in February 2018 at Salvador B. Castro Middle School, just west of downtown, when authorities say a gun that a 12-year-old girl had in her bag accidentally discharged during her seventh-grade class, injuring one student in the wrist and another in the head.

The shooting happened in science teacher Sherry Zelsdorf’s classroom. In the aftermath, she said, some students told her they felt safer coming to school knowing there were random searches even though those searches hadn’t kept the gun off campus.

Still, Zelsdorf said, it is shortsighted to sunset a policy without knowing what the new safety measure will be. “I would have liked to see a new plan to vote on,” she said.

L.A. Unified Supt. Austin Beutner did not comment on how he would develop a plan or what might be in it. In a news release, he said: “We must keep our students and employees safe, while promoting a positive school-going climate at every campus.”

Students need better ways to report weapons, such as anonymous texting, and programs to build trust with staff, Zelsdorf said.

In the past decade, said L.A. schools Police Chief Steve Zipperman, the district has tried to shift from a punitive approach and focus on developing relationships with students. Some school police officers are involved in intervention and restorative justice programs, which counsel students how to diffuse conflicts, as early as elementary school, he said.

“I think that part of the school’s responsibility would be to maybe educate kids on how to manage their emotions and how to respond if you have a stressful event without violence,” Zelsdorf said.

Zelsdorf now teaches at Paul Revere Charter Middle School in Pacific Palisades, where monthly homeroom assemblies emphasize the need for students to be kind to each other, and there are support staff on campus to address students’ mental health needs. Kids, she said, feel comfortable telling adults about potential problems between students.

Zelsdorf remembers that the students in her class at Castro Middle School were eerily quiet in the minutes before the shooting. She later found out they had figured out there was a gun in the class, but no one said a word about it.

Times staff writers Iris Lee and Howard Blume contributed to this report.

Reach Sonali Kohli at Sonali.Kohli@latimes.com or on Twitter @Sonali_Kohli.

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.