Subs crossing the picket line, iPad learning: Inside the LAUSD strike at one school

Scenes from Day 2 of the teachers’ strike at John Burroughs Middle School

On a normal morning, the second floor of John Burroughs Middle School in Hancock Park would be bustling between classes, full of the sounds of students learning and teachers teaching.

But on Tuesday, there was near silence as Assistant Principal Susan Armendariz walked down the empty hallway.

“It makes me sad to not hear the students in their classes,” she said. Out of about 1,700 students, 723 had shown up Monday, 768 on Tuesday.

Each one who arrived was assigned to a large space — multipurpose room, cafeteria, auditorium — and staff members took roll both manually and online, asking students using iPads or phones to visit a link and mark themselves present.

Then student leaders wearing special lanyards around their necks took the attendance sheets to the main office.

Last week, as the school prepared for the strike, administrators asked the student leaders if they would be willing to help out, Armendariz said.

So they were on hand not just for attendance, but also to do things like try to help their peers with technical problems on their school-issued iPads. One student leader was in the front office along with the staff. As parents kept arriving to pick up their children early, he greeted them, asked them to sign in, gave them yellow visitor stickers and directions if needed.

In between, he did an assessment for an online course from a company called Edgenuity so that he’d be given appropriate “mini-lessons.”

At Burroughs, it helps that every student has an iPad, from the era when former superintendent John Deasy began rolling out his controversial program to provide them to all students.

For the strike, the school asked students to bring them in, fully charged. Armendariz said it will be useful later to see the assessments and find out more about what help students need.

Teachers and instructional coaches also left behind lessons on a platform called Schoology, said Principal Steve Martinez.

The tablets, of course, are not teachers, he said, as he welcomed students trickling into the school Tuesday morning.

“We are doing our best with the resources that we have,” he said.

Outside, teachers were picketing.

Among them was Christina Silva, a special-education teacher, who said she felt torn about leaving the classroom but felt the potential gains were worth it. The teachers are demanding smaller classes and more support staff — nurses, librarians, counselors — for their students. Mental-health support and more one-on-one attention will help her students learn better, she said.

Silva is one of more than 70 UTLA members who work at the school and are striking. In their place on Tuesday the school was assigned nine substitutes, as well as one district employee who has teaching credentials but isn’t a UTLA member, and two classified staff, Martinez said. No regular parent volunteers have showed up to help, and Martinez didn’t try to get new ones.

Students must be supervised by employees with teaching credentials, and that’s his priority, he said. But he doesn’t know at the start of each day how many adults he’ll have. So he starts the students in the big spaces and then moves them to classrooms according to their level of need.

The first priority Tuesday was to try to assign substitutes to the 100 or so students with special needs. Those usually educated in separate groups were the first redirected to classrooms staffed with a substitute teacher and the paraprofessionals and special education aides who usually work with them (and belong to another union).

“Any sort of change in their usual routine can be very stressful,” Armendariz said. The school uses federal Title 1 funds, meant for schools with high populations of low-income students, to pay for a full-time nurse — a rarity in the school district where nurses are funded only one day a week. The school also pays to keep a school psychologist on campus full time, and a psychiatric social worker. (The union would like for the district to pay for full-time nurses and psychiatric social workers at all schools.)

During the strike, a school staff member who is not a nurse is assigned to the nurse’s office, and each area with students has a backpack with emergency supplies. Jacklyn Freyberger, a “navigator” assigned to the school through the district’s Healthy Start wellness program, remains on campus to provide short-term counseling to students. And though she does not have the credentials of a psychiatric social worker or school psychologist, she can refer students and families to off-campus resources, she said.

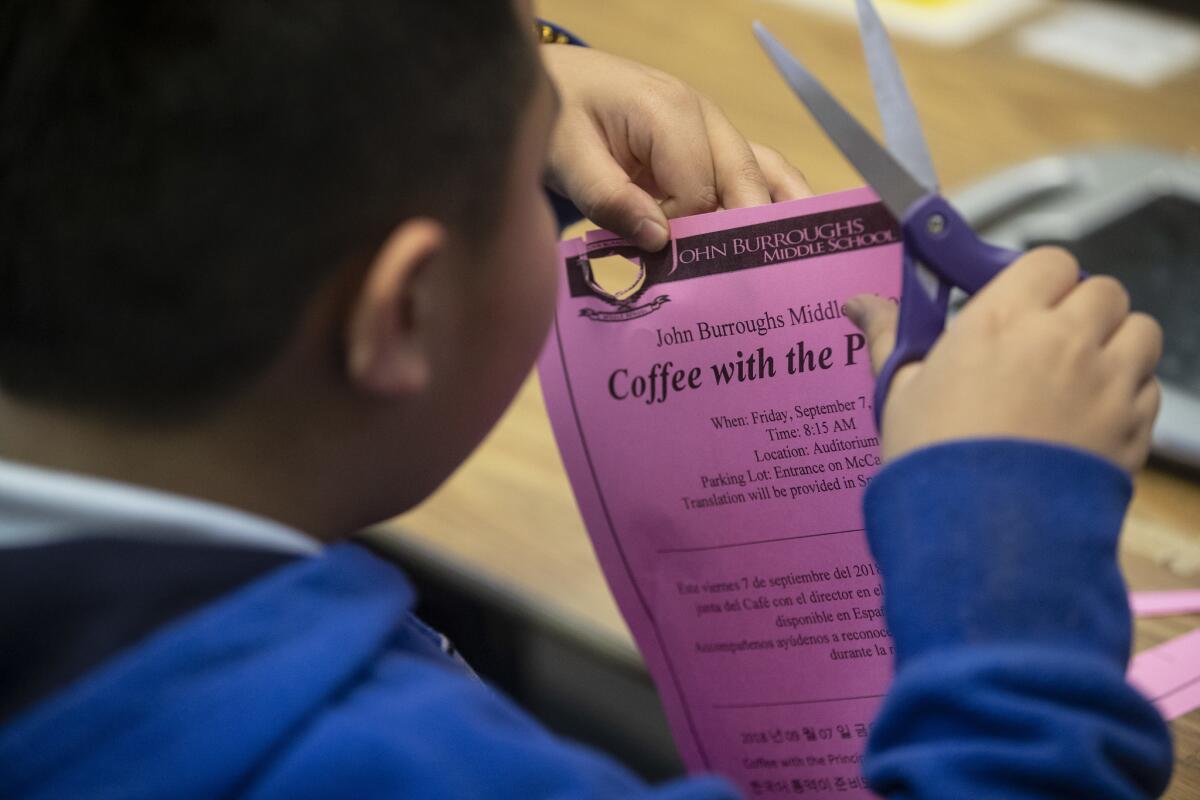

L.A. Unified substitute Wayman Washington was in a classroom Tuesday, watching over four children with moderate to severe autism. There, where the need was great, there were as many adults present as children. Two students, along with a special-education aide and a behavior-intervention aide, watched a movie on an iPad. Another cut green paper with scissors, while an aide put an adhesive bandage on the wrist of the fourth student for a cut he had gotten before getting to school.

Most students, though, remained in the large spaces, working on their own on their iPads, if they brought them, in workbooks or on their cellphones.

As Martinez walked into the multipurpose room Tuesday morning, a student ran up and asked, “Do you know how long the strike is, Mister?”

In that room, a substitute and an assistant principal, sometimes with a classified staff member, watched over about 75 seventh-grade students, encouraging them to do some work.

By 11:15 a.m., just before lunch, some students were restless. They huddled around phone screens, played Uno or talked.

The substitute in the multipurpose room is a regular district sub and a UTLA member who decided not to strike out of financial necessity. “I have a 7-week-old at home who’s getting foot surgery today,” he said. He declined to give his name.

He said the district was paying him more than the usual rate, but would not say how much. “It’s worth it, let’s just say that.”

Another sub — who walked around a gym filled with 150 students sitting at long tables — said he was hired through an outside agency.

Newly credentialed, he applied for a job at the Charter Substitute Teacher Network last week, and the agency contacted him Friday to ask if he would be willing to work during the strike.

He didn’t want to give his name but said he was getting paid $160 a day. That’s less than the district rate for an employed, credentialed K-12 substitute, though the district is paying the Charter Substitute Teacher Network considerably more; their contract with the school district lists a daily rate of $250.

He said he was conflicted about crossing the picket line, but he also has $50,000 in student loans to start paying off.

“I fully understand what they’re doing. I support them,” he said of the striking teachers. “But in the back of my mind it’s like, if it’s not me it’s somebody else.”

Reach Sonali Kohli at Sonali.Kohli@latimes.com or on Twitter @Sonali_Kohli.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.