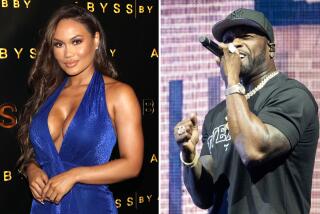

Anti-rap crusader under fire

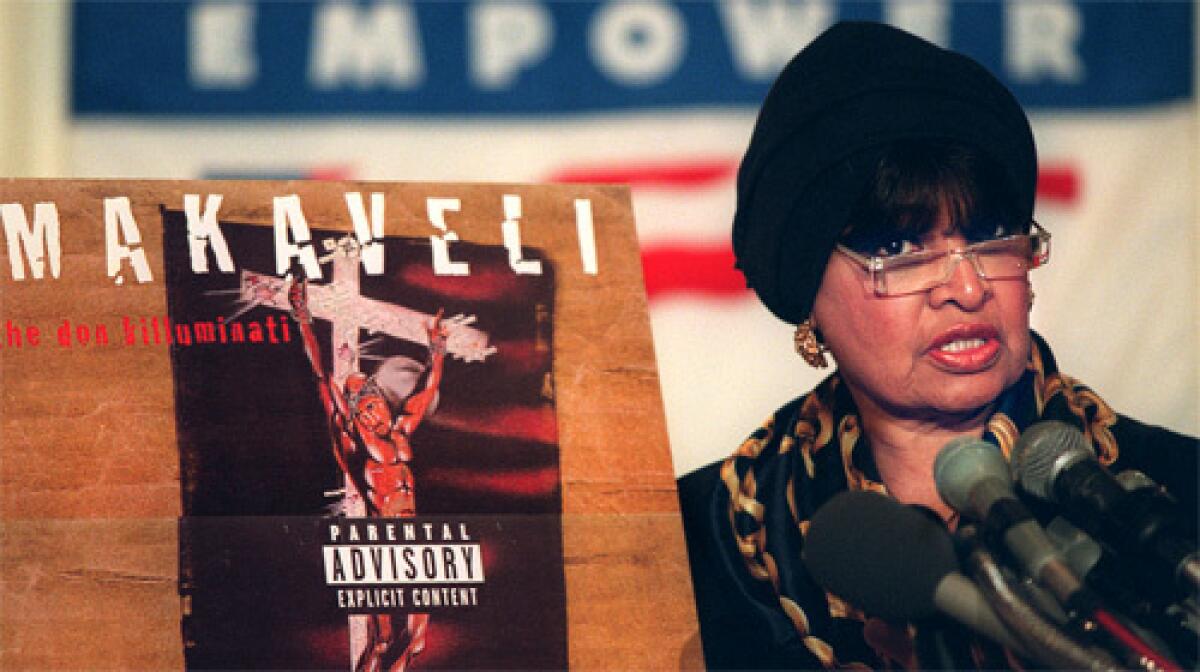

C. DeLores Tucker captured the outrage of many parents three years ago when she declared war on gangsta rap music. Prominent politicians leaped to her side. She became a celebrity by denouncing companies that “pimped porno rap” to children.

The 67-year-old African American feminist never stopped the distribution of any music. But now she is embroiled in an increasingly bitter and personal dispute with Death Row Records, home to such rap stars as Dr. Dre, Tupac Shakur and Snoop Doggy Dogg.

Instead of leading a moral crusade, she spends her time defending herself against a civil lawsuit that suggests she had an economic motive for criticizing rap music. Her credibility has been challenged by accusations that she misrepresented her educational credentials, profited from ownership of slum properties in Philadelphia and was fired as Pennsylvania’s secretary of state for using her post for personal gain.

The allegations, which she denies, were dug up by a hard-nosed San Francisco detective firm, Palladino & Sutherland, retained by Death Row. The Westwood-based record company sued Tucker last summer for contractual interference, alleging that she tried to persuade it to break a deal with Interscope Records, its distributor. The lawsuit was filed one month before Time Warner dropped both Death Row and Interscope as the national rap controversy escalated.

Tucker says the lawsuit is nonsense. Death Row, she says, launched its “smear campaign” for one reason only: to silence her.

“They want me to back off, but I won’t,” Tucker said in a phone interview from the headquarters of her Washington-based nonprofit organization, the National Political Congress of Black Women. “It’s important to pay attention to who is dredging up all these charges. Remember, these are the same people who are out there pimping pornography to your children. Their record and records speak for them. I’ve been an activist all my life. My record speaks for itself.”

Death Row CEO Suge Knight says he hired the detectives to investigate allegations raised in the lawsuit, as well as to find out about Tucker’s background and her motivations for attacking his company. (Legal experts say hiring private detectives for this kind of work is standard practice in business lawsuits.)

“C. DeLores Tucker is a phony,” Knight says. “She is making a career out of disrespecting Death Row and our artists by pretending to be some great moral guardian. It’s time that people found out who the sister really is.”

Tucker’s record in politics and civil rights has been well-documented in Philadelphia newspapers.

One of 11 children of a Bahamian preacher, Tucker spent much of the 1960s marching with Martin Luther King Jr. and raising funds for social and political causes within the Democratic Party.

Founder of the Martin Luther King Jr. Assn. for Non-Violence, she has long championed equal rights and economic opportunity for African Americans, especially single mothers and young males.

She often invokes King’s name when attacking the lyrics and lifestyles of such Death Row stars as Snoop Doggy Dogg, who was acquitted of murder last month, and Shakur, who is appealing a sexual abuse conviction.

“The pimps in the entertainment industry who distribute gangsta rap are major contributors to the destruction of the African American community,” says Tucker, who counts among her friends such venerable figures as Rosa Parks, Maya Angelou and Coretta Scott King.

“What do you think Dr. King would have to say about rappers calling black women bitches and whores? About rappers glorifying thugs and drug dealers and rapists? What kind of role models are those for young children living in the ghetto?”

Ghetto life is familiar to Tucker.

Her father was an unsalaried pastor at a church he founded in north Philadelphia, one of the city’s most poverty-ridden neighborhoods. Her mother paid the bills by running a grocery store and renting dozens of tenement buildings that she owned to indigent black families that had moved north in search of factory work.

Tucker inherited 24 of those buildings from her mother in 1959, the year her husband opened a real estate company. Tucker says they remodeled the buildings with government loans and leased them out as single-family dwellings to tenants chosen by the city.

One year after Tucker marched with King in Selma, Ala., in 1965, inspectors ruled that 10 of her Philadelphia tenements were in substandard condition and were a threat to the lives of the occupants. A 1966 Philadelphia Inquirer article listed the Tuckers among the city’s worst slumlords.

Tucker calls the allegations “ridiculous.”

“We are not slumlords and never have been,” she says. “We used to own properties in the inner city that we rented to displaced women on welfare with six or seven children who couldn’t get housing anywhere else. We tried to help them, but the tenants never paid their rent. Plus, they tore up the buildings. It got to the point where they had to all be boarded up. So you tell me, who is responsible?”

Newspaper accounts indicate that the majority of the buildings owned by Tucker’s family were boarded up during the 1970s after being cited for a succession of tax, safety and health code violations. Tucker says the structures were either abandoned, taken over by the city or donated to charities.

“Slumlord is a charge that you could smear even the best mayor in this nation with,” Tucker’s husband, William, said in a phone interview. “After all, it’s the mayor who is in charge of the public housing projects. In Philadelphia, for instance, things got so bad in the projects that they had to just blow a bunch of them up. Let’s be honest, even the government can’t maintain these slums.”

The couple got rid of the north Philadelphia properties before 1971, when Gov. Milton Shapp appointed Tucker commonwealth secretary of Pennsylvania, a $30,000-a-year cabinet post equivalent to secretary of state.

Tucker was the highest-ranking black woman official in any state government, according to newspaper articles written at the time. During her six years in the post, she is credited with helping to streamline the voter registration process in congressional elections.

But Tucker’s reign ended abruptly in 1977 when Shapp fired her, accusing her of using the office for personal gain. He said she asked state employees to write speeches for which she collected $65,000 in honorariums, some of the money from charities under her supervision.

Tucker’s dismissal was criticized by the Rev. Jesse Jackson and other black activists as unjust and politically motivated.

“The only reason I got fired was because I refused to support someone the governor had designated as his heir who was going to dismantle the affirmative action program I fought so hard to put in,” Tucker says.

An investigation conducted by Philadelphia Dist. Atty. LeRoy S. Zimmerman in 1977 found that Tucker used state employees to research and write speeches for which she was paid thousands of dollars. No criminal charges were filed.

Zimmerman said in an interview that he chose not to prosecute primarily because he viewed Tucker as “a very effective ambassador of the state whose speeches encouraged minorities to participate in government.”

Tucker has had no luck in resurrecting her political career. She ran for lieutenant governor, U.S. senator and congresswoman, but never made it past the primary elections.

A year after her last political defeat in 1992, Tucker decided to launch her national crusade against rap, at the request of prominent members of the National Political Congress of Black Women.

Sandra Mills, the campaign manager of Tucker’s failed bid for Congress, says the family’s involvement in low-income property ownership has dogged Tucker throughout her career.

“Everybody has some baggage in their past and in C. DeLores Tucker’s case, the baggage is in bad property management,” Mills said in a phone interview from Philadelphia. “But I don’t see how that diminishes in any way the public service she is performing for African Americans by fighting against the negative lyric content in rap music.”

Death Row head Knight disagrees.

The way he sees it, questions about Tucker’s real estate business undermine her credibility as a rap critic. And according to Knight, they aren’t the only problems.

Tucker has frequently accused white record executives of forcing black rap artists to “get down in the gutter and use pornography and profanity” in order to obtain a contract.

Knight says rappers at Death Row, the most successful black-owned company in the industry, laugh at Tucker’s remarks. In fact, he credits Death Row’s swift rise to the fact that black artists on his label retain complete creative control over their music.

According to the lawsuit brought by Knight’s company, Tucker is the one who tried to persuade him to yield creative and financial control of his label. The lawsuit alleges that Tucker asked Knight to sign a document last summer designating her as Death Row’s exclusive representative to negotiate a new “clean” rap venture that she said would be financed by Time Warner.

The lawsuit charges Tucker with contractual interference, extortion and unfair business practices. According to the suit, Tucker told Knight that if he didn’t work with her, her organization would use its “power to cause the government to go after Knight” and the artists on his label, several of whom are on probation for criminal offenses.

Tucker says she did nothing wrong. “The lawsuit is nothing more than an attempt to stop me from going after gangsta rap,” she says. “Sure, we talked with Suge Knight, but the allegations in the suit are just lies.”

Knight says his private detectives--who also investigated high-profile cases involving President Clinton, Michael Jackson and John DeLorean--have dug up other skeletons in Tucker’s closet.

They say she upset Jewish groups in Philadelphia during her 1992 congressional campaign when she criticized her opponent for not hiring black women for his staff while retaining a Jewish woman. Tucker maintains that the remark, made on a local radio talk show, was misconstrued.

Tucker also has raised eyebrows in the music industry for citing the work of Frances Cress Welsing, a Washington psychiatrist whose controversial racial theories have angered the Anti-Defamation League. The league released a statement criticizing Welsing for quotes attributed to her in George magazine regarding Jewish involvement in the production and distribution of gangsta rap music. Welsing, who maintains that her remarks were distorted in the publication, says it is “ludicrous and absurd” to call her anti-Semitic.

Welsing’s writings were endorsed six years ago by a member of the rap group Public Enemy, a move that triggered protests from Jewish executives at the rappers’ record company. Tucker invited Welsing, whom she calls a “renowned psychiatrist,” to speak last year at a fund-raiser staged by the National Political Congress of Black Women.

Tucker adamantly insists that she is not anti-Semitic. “I have nothing but respect for the Jewish people,” she says. “The Jewish people have been our greatest allies in our struggle for justice. These smears against my character are outrageous.”

Knight says his detective team also uncovered evidence that Tucker--who refers to herself as the Honorable Dr. C. DeLores Tucker--never graduated from college. She derives her title from honorary degrees issued by Morris College in Sumter, S.C., and Villa Maria College in Erie, Pa.

Tucker declined comment.

“DeLores Tucker is a hoax,” Knight says. “She pretends to care about the black community, but if you look into her history, you find she was a slumlord. She pretends to want to help young black males, but she’s trying to destroy a company owned and run by them. She pretends to be a doctor. But hey, she’s about as much of a doctor as Dr. Dre is.”

Tucker filed a complaint in January with the U.S. Justice Department and the FBI about gangsta rap being sold to minors. A source in the agency says the department is reviewing the rap lyrics that she submitted.

She also called for a national boycott of Tower Records, which she says advertises the sale of violent and sexually degrading rap in major newspapers. That boycott is endorsed by the Congressional Black Caucus, the National Organization for Women, the Parents Music Resource Center and the National and Progressive Baptist Conventions.

Her crusade continues to draw support from such politicians as Republican presidential front-runner Bob Dole, Sens. Joseph Lieberman (D-Conn.) and Carol Moseley-Braun (D-Ill.) and former federal drug czar William Bennett. Tucker’s supporters declined comment, but privately disclaimed knowledge of her past.

Tucker spent much of February giving depositions for Death Row’s lawsuit and is scheduled to undergo another round of depositions next week. She vows not to let Death Row’s “smear campaign” interfere with her efforts to abolish gangsta rap.

“I guess this is the price a person pays for dedicating their life to fighting for justice in this country,” she says. “Dr. King gave his life. Rosa Parks had to suffer. And now they’re coming after me. But I will never quit. I promise you that either this gangsta porno rap is going to die or I’m going to die trying to stop it.”

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.