Bell’s neighbors no strangers to public corruption

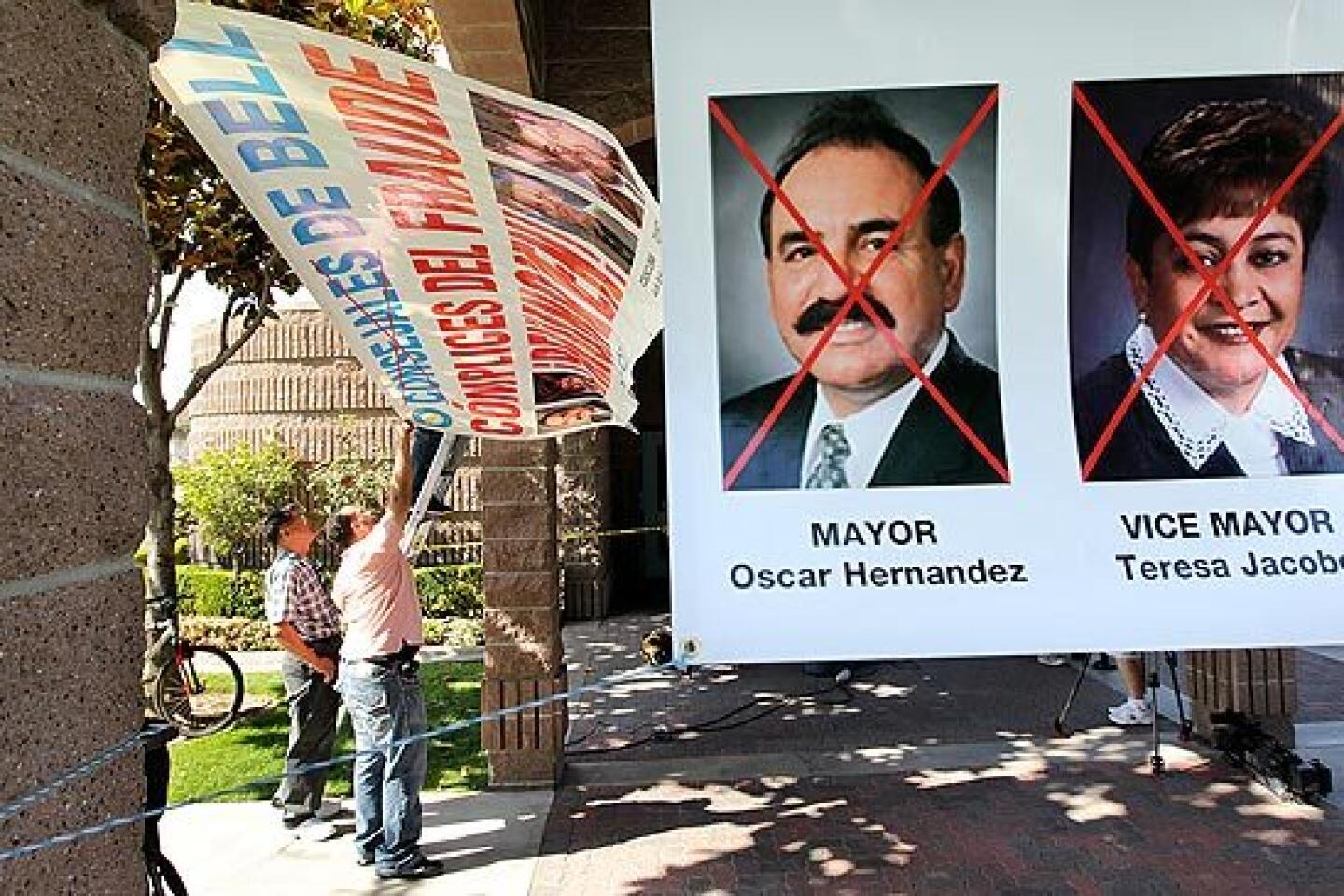

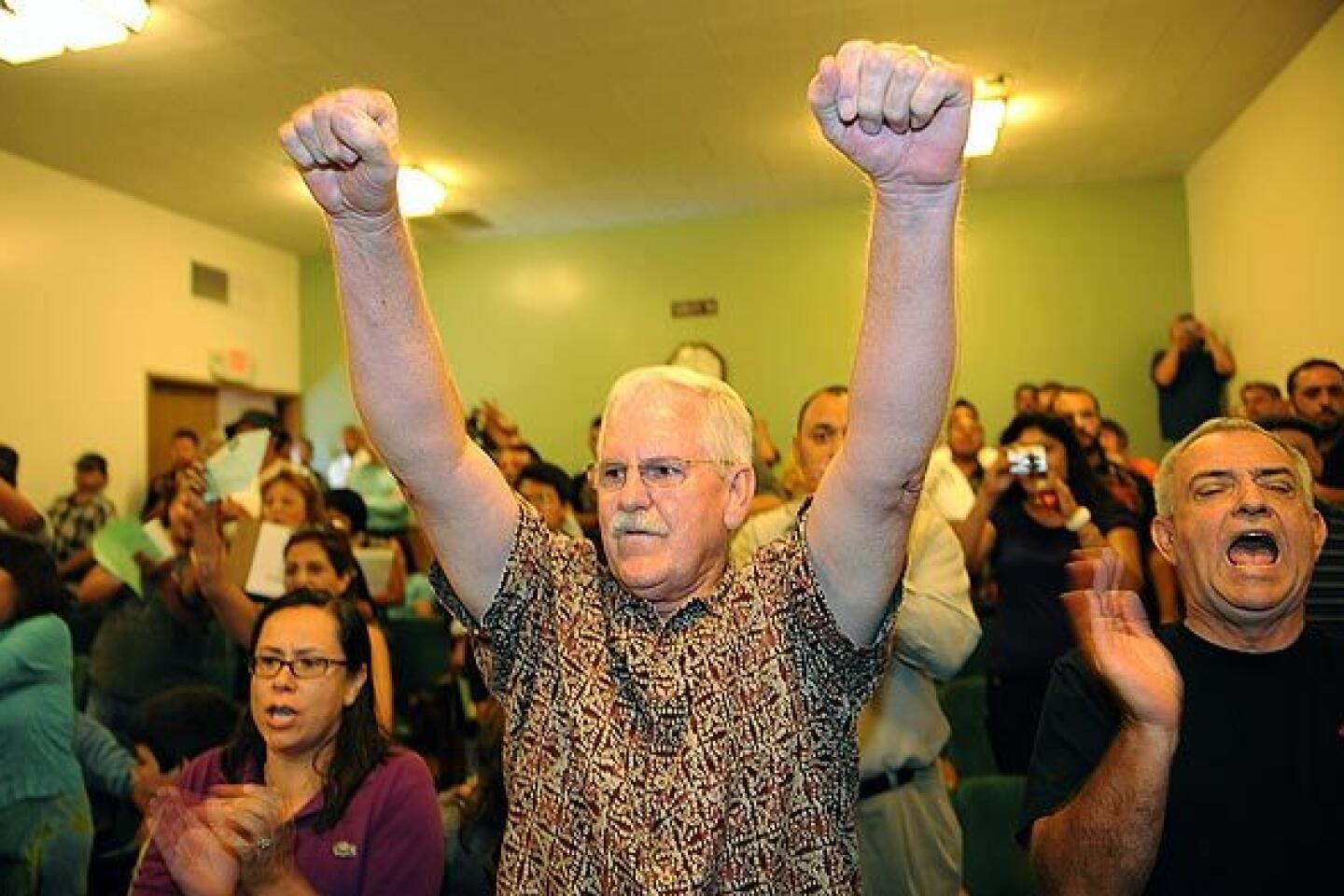

They flooded Bell City Hall with requests for public records and packed a council meeting with an overflow crowd.

They collected signatures demanding an audit of city officials’ salaries and vowed to boot their handsomely paid politicians out of office. They even created a website and posted documents that the city refused to put on its official site.

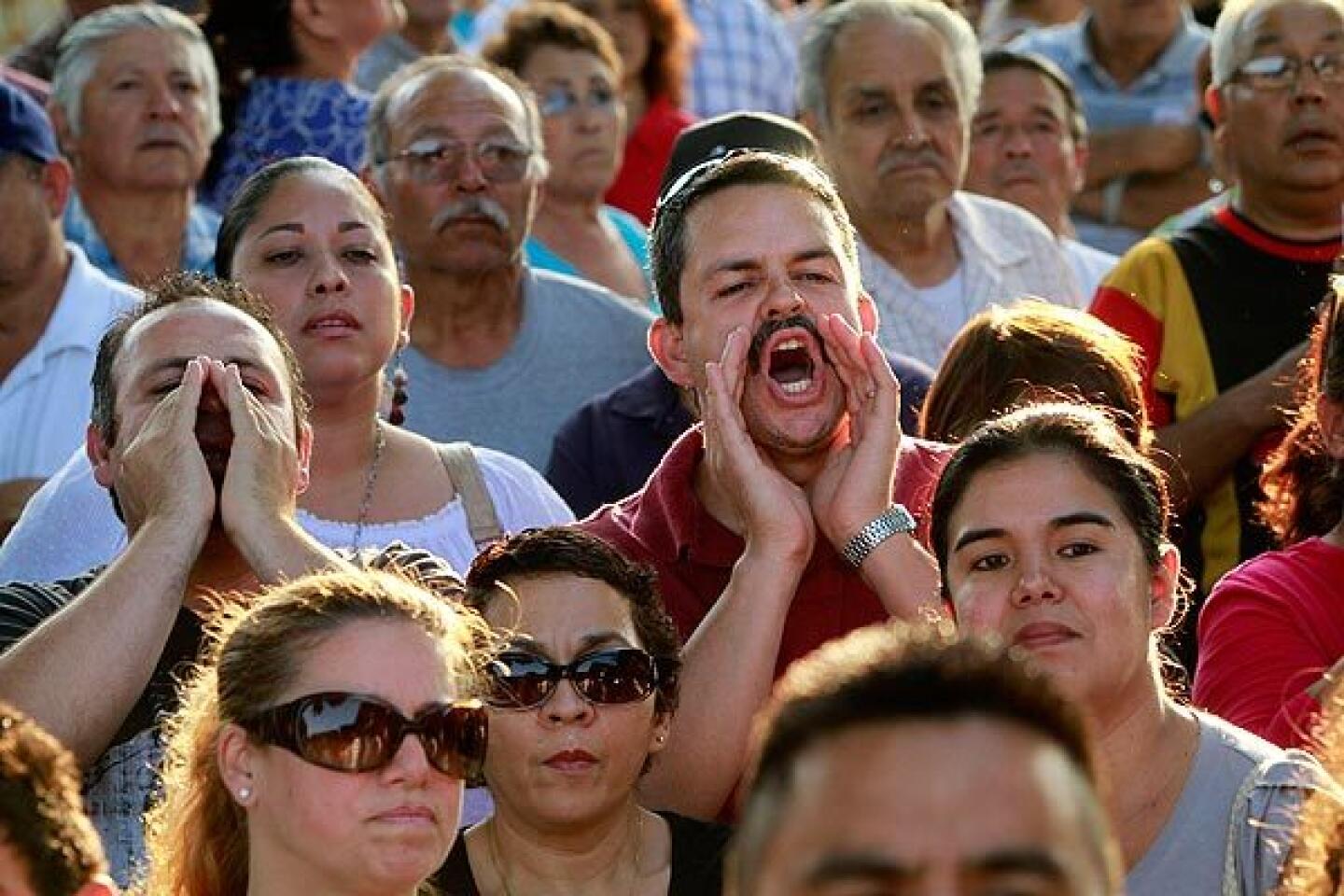

In the week since residents in this working-class suburb discovered that their city manager makes nearly $800,000 a year, Bell has experienced a sudden jolt of civic engagement. It’s an anger-fueled form of participatory democracy that’s relatively new for an immigrant-heavy town of about 40,000 not known for high voter turnout.

But the sudden burst of outrage follows a pattern all too familiar in southeast Los Angeles County, where municipal corruption has been a recurring problem in part because few people were paying attention to how local government operated.

The question in Bell is what happens next: Is the boom in citizen participation going to be short-lived? Or will it create a more engaged political culture that endures?

Neighboring towns show both the promise and the potential setbacks.

Residents rose up in South Gate seven years ago, pushing out city leaders who were eventually charged with plundering the city treasury. Residents and activists have stayed involved at South Gate City Hall, and many agree that has made the government more accountable and transparent. The Los Angeles County district attorney’s office said it has not received a complaint about South Gate government since then.

But those who helped bring about the change said it required residents to think differently about their role in city government.

South Gate, like many southeast L.A. County cities, has large immigrant populations from Mexico and Central America. Many work long hours, don’t speak English and have a distrust of government carried over from their homelands.

“What happened was a civic movement, not a campaign,” and Hector De La Torre, a South Gate reformer who is now a state assemblyman. “Whether they were Latino immigrants or third-generation Latinos, or older white residents, or blacks or Asians, it brought the community together.”

Farther south, in Lynwood, weeding out problems at City Hall has proved more difficult. The city has been rocked by several corruption scandals in the last decade. In the early 2000s, Mayor Paul Richards and other council members were accused and later convicted of steering city contracts to a front corporation he secretly owned.

In 2007, five Lynwood City Council members and former members — including some billed as “reformers” — were indicted for using hundreds of thousands of dollars in public funds to illegally boost their salaries, pay for personal expenses and even hire an exotic dancer at a “gentleman’s club.”

Residents finally rebelled after the council proposed razing homes to build an NFL stadium in the city, prompting a recall election that swept out four of the five council members.

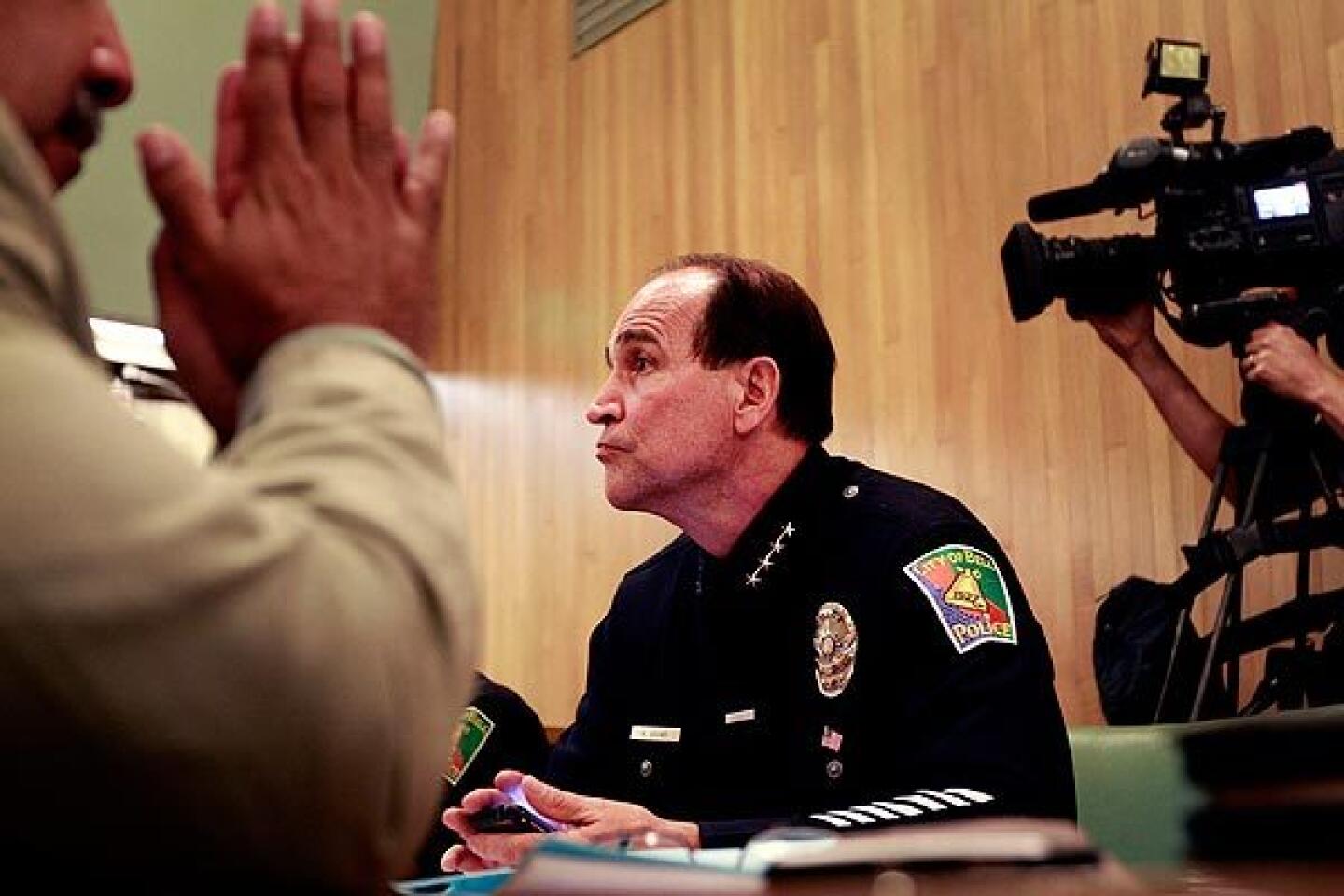

Although prosecutors have brought charges against dozens of southeast L.A. County officials over the last two decades, they say it’s public participation that is the key to fixing many of these governments.

“We deal with the crime. What people consider corruption may not be a crime,” said David Demerjian, head of the district attorney’s Public Integrity Division. “I tell them, ‘Any dysfunction within the government has to be handled by you.’ The residents have a lot of power.”

For many in southeast L.A. County, South Gate’s history offers the best example of what is possible when residents get involved in civic affairs.

South Gate had endured several years of alleged malfeasance. It got worse in 2000, when a politician named Albert Robles engineered a recall that won him a majority of allies on the City Council.

Robles unleashed a reign of governance so flamboyant in its nasty badness that “South Gate” became shorthand for corruption and politicians gone wild.

Robles and his allies awarded themselves hefty raises, retaliated against critics and hired a gaggle of expensive lawyers — which almost caused the city to buckle financially. The city raffled off a house at taxpayers’ expense. Elections were rife with smear campaigns, including one in which an opponent of Robles was falsely accused of being a child molester.

“We were talking about a dictatorship. That’s exactly what it was,” said Henry Gonzalez, 75, a longtime South Gate councilman and critic of Robles who was shot by an unknown gunman outside his home in 1999.

Eventually residents, including the city’s large immigrant population, joined together and recalled Robles from office in 2003. The first council meeting after his ouster turned into an impromptu celebration of democracy, with hundreds of residents joining officials from around the region in a show of support for the new officials.

“This is our first meeting of a free and honest South Gate. I’ve got to tell you, I feel good,” then-state Assemblyman Marco Antonio Firebaugh (D-Los Angeles) said at the meeting.

Three years later, a tearful Robles was sentenced to 10 years in federal prison for plundering more than $20 million from the small, working-class city.

The city embarked on the arduous task of reversing years of damage, including suing law firms that netted millions from the Robles machine. It was something akin to a political exorcism, but for the entire community, Gonzalez said, the experience was cathartic.

“It was the greatest thing to ever happen here,” he said. “It was beautiful.”

After leaving the City Council, De La Torre went to Sacramento, where he has used his South Gate experiences to push for laws to keep municipal governments honest.

After the scandal about the Lynwood council salaries, he got a law passed limiting compensation for part-time council members. The Bell council members were apparently able to avoid that restriction by becoming a charter city. Now they’re considering pay cuts as they’re threatened with recalls.

De La Torre said he was stunned when he found out that Bell City Manager Robert Rizzo was being paid nearly $800,000 a year. It made him think of former Vernon city administrator Bruce Malkenhorst Sr., who made more than $600,000 and was indicted for public corruption, then retired with a record-high state pension of $500,000.

“I’ve heard of keeping up with the Joneses,” De La Torre said. “I guess [Rizzo] was trying to keep up with the Malkenhorsts.”

Cal State Fullerton political science professor Raphael Sonenshein said he hopes residents in Bell make use of public records as well as state law to help create a transparent government that they can trust for years to come. But in the meantime, he said, they have taken the first step: They got informed.

“And when the people found out, they didn’t make excuses,” he said. “They got angry.”

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.