Diocese of Orange, Archdiocese of Hanoi become ‘sisters’

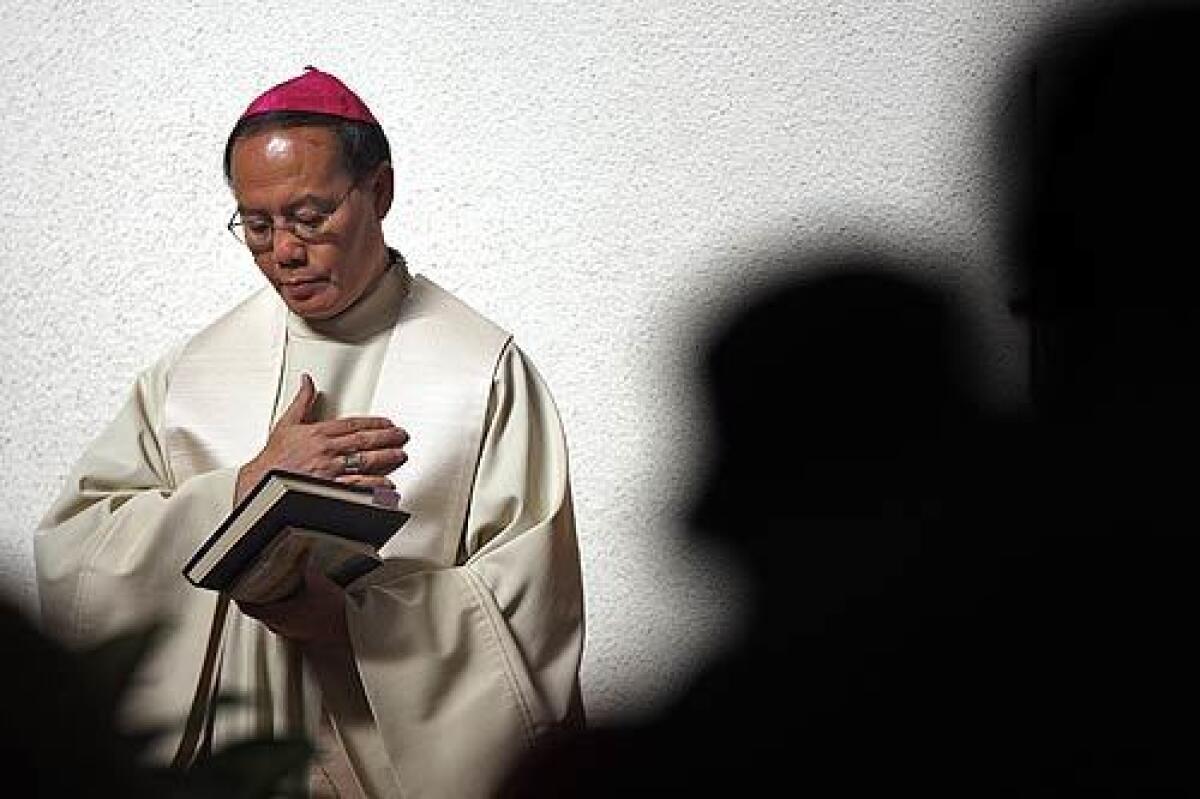

The first time that Archbishop Joseph Kiet Ngo of Hanoi visited Orange County, he was struck by the energy and passion the Vietnamese community had brought to the Roman Catholic Church in the United States. He met dozens of Vietnamese American priests, attended Vietnamese Masses and talked to parishioners.

“I admire Vietnamese Catholics here,” said Ngo, the archbishop of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Hanoi. “They live their faith more actively than in Vietnam.”

From that visit, Ngo came up with an idea to create a partnership between the archdiocese in Vietnam and the Diocese of Orange.

He wanted Catholics in Vietnam to learn from their American counterparts.

This week, Ngo is making his first church-sanctioned trip to Orange County to kick off the “sister diocese” relationship. Under the partnership, the Diocese of Orange for the first time will sponsor four seminarians from Vietnam in their training to become priests. The diocese will also send priests to Hanoi to teach English and at seminaries.

“We are now linked to people who share our faith but who live in another country,” said Bishop Tod Brown of the Diocese of Orange.

“The experience will be beneficial not just to our Catholic Vietnamese community but with the broader community as well.”

Ngo’s visit carries spiritual and political significance in Orange County’s Little Saigon, where anger still runs deep toward the government of the country that many fled decades ago. It links Hanoi, the capital of Vietnam that was once isolated from the world, to the largest population of Vietnamese outside of the country.

While many Vietnamese Americans still harbor resentment toward the Communist government, their religion has tied them to Catholic churches in Vietnam, said Father Tuan Pham of the Diocese of Orange.

Many Vietnamese American Catholics have donated to Vietnamese churches over the years, and dozens of priests from Vietnam have come to Little Saigon in the last 10 years, though not with the church’s official blessing, Pham said.

The Catholic community in Little Saigon has grown quickly since Vietnamese refugees started arriving after the fall of Saigon in 1975. Starting from a single Vietnamese Mass, there are now 14 Orange County parishes that host 53 Vietnamese Masses each week. Of the 181 diocesan priests in Orange County, 43 are Vietnamese.

Since Ngo arrived Tuesday, he has been huddled with diocese officials hammering out details for the sister partnership, but he did take a one-day break for a visit to Disneyland with Pham.

Ngo’s big public events with the Vietnamese American community come this week, when he will participate in Vietnamese Masses.

Ngo will also ask for donations to help rebuild churches destroyed during the Vietnam War. He will be sent off with a celebration at Santa Ana’s Vietnamese Catholic Center on Sunday.

In the United States, about one-third of Vietnamese are Catholic. In Vietnam, Catholics make up about 7% of the population, which is predominantly Buddhist.

At the end of the Vietnam War, the Communist government imposed tight restrictions on the Catholic Church, but those have loosened in recent years, Ngo said. The government allows priests to be ordained every year instead of every six years, as was the rule in the 1980s. Even so, Ngo said, parishes in Vietnam have had difficulty establishing schools and hospitals.

“Vietnamese people in America have education, they have jobs, they have a better way of life. It is easier for them to live out their faith,” Ngo said. “In Vietnam, they are more limited to what they have in terms of finance, and that can make them less open minded in terms of practicing our faith.”

Ngo said he admires the fact that the United States is a secular society that is also very faithful. Ngo said that as Vietnam develops and changes, he has seen young people leave rural villages to find work in bigger cities, only to face challenges keeping their faith.

“As Vietnam develops, it is hard to balance that with making money and having a job in the city and being away from your family and still having your religion grounded,” Ngo said.

“We are a rural country and traditional society that is changing quickly. We don’t have experience of living faith in the modern country.”

Ngo said he hopes the seminarians from Hanoi will learn this during their stay in America to bring back to Vietnam.

Ngo, born in the northern city of Lang Son, encountered his own difficulties while on the path to becoming a priest in Vietnam. Ngo’s family feared persecution from the Communists and fled south in 1954, part of an exodus of Catholics and other Northern Vietnamese to a part of the country that was perceived to be more tolerant. At the urging of his parents, Ngo entered the seminary when he was 12.

He was three years away from becoming ordained when the South Vietnamese government collapsed in 1975 and the Communist government would not allow new clergy to be ordained.

Ngo recalls the diocese bishop saying, “You will never be an ordained priest.”

Many classmates decided to leave the seminary, but Ngo did not give up. “I accepted that,” he said. “I thought, I would like to consecrate my life to God and God could make use of me as he likes.”

He worked as a beekeeper and tended goats while doing pastoral work for his parish. After the breakup of the Soviet Union, Vietnam’s policy became more open, and Ngo was finally ordained in 1991. He became bishop of Lang Son diocese in 1999 and archbishop of Hanoi in 2005.

After the Diocese of Orange established its partnership with Hanoi, other dioceses in the United States followed. The Diocese of Los Angeles and the archdiocese of Saigon, for instance, are now sister dioceses.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.