Building a house for his family, but father can’t live in it

PURISIMA DE TEMASCATIO DE ARRIBA, Mexico — The six brothers and sisters ambled down the hill in this ranching village, singing, laughing and kicking rocks, serenaded by cock-a-doodle-doos and baaa-baaas.

There were Omar and Teresa and Noe and Maria and Carlos and Marcos, followed by their mother, Gabriela Ireta, who shooed away stray dogs and steered her children around the puddles and potholes.

“Here comes the mama duck and her ducklings,” the villagers liked to say.

In their cluttered one-room house, six backpacks hung from a wall, six plates of chicken and beans lined the table at dinner, six bikes and helmets crowded a corner. The boys slept in one bed; the girls in another. In the morning, they would shower in groups and barrel out the door to get to school on time.

Bus drivers did double-takes. Schoolmates jostled for a peek. Teachers came from miles around to study their progress. Sextuplets! In this part of Mexico, the central state of Guanajuato, no one had ever seen such a thing. Only four other sets of sextuplets existed in all of Mexico.

“We saw them as a blessing,” said Janet Ramirez, who watches the family walk by her house on the way to school.

But others didn’t know what to make of the sextuplets, who showed up one morning three years ago, not long before their sixth birthday. When Teresa and Maria skipped rope, they counted in English. And the boys preferred passing a football instead of kicking a soccer ball.

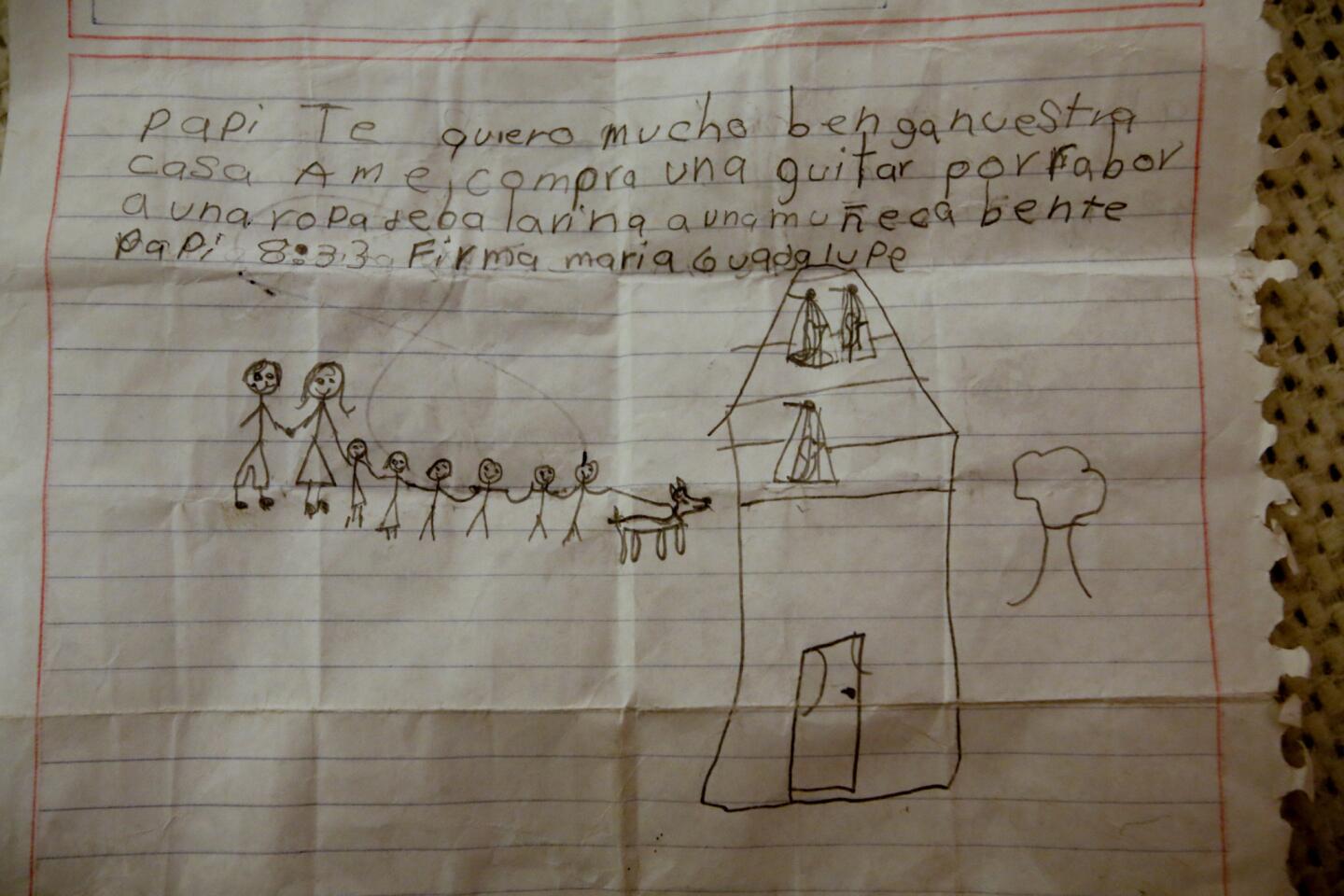

At home, the children would badger their mother: When will we see our father again? Will we ever get our own beds to sleep in? Why do people call us gringos?

Carlos, the quietest and most curious of the bunch, could never grasp why he and his siblings could get on a plane and fly to see their father in California, but their mother couldn’t.

“Because I was born here in Mexico,” Gabriela said. “If I try to cross into the U.S., the police will take me to jail.”

::

It was the summer of 2004, and Gabriela’s belly was heaving on her 30th day of bed rest at UC San Diego Medical Center. Benigno, her house-painter husband, held her hand as a team of 40 doctors and nurses gathered in the delivery room.

Gabriela, then 24, suffered from a hormonal imbalance, polycystic ovary syndrome, that prevented her eggs from being fertilized. Fertility pills hadn’t worked so she started taking hormone injections.

They were too expensive for immigrants like Gabriela and Benigno, then 32, who were in the country illegally; Benigno for 10 years; Gabriela, four. Their doctor, Johanna Archer, paid for the treatment. “I felt they deserved the chance to have a child,” she said.

Benigno showed his appreciation the only way he could.

“He offered to paint my house,” Archer said.

Archer thought the injections would help fertilize at most two of Gabriela’s eggs. Instead, four smaller eggs also bloomed embryos.

On Sept. 15, 2004, the babies were born over a six-minute span. They were five weeks premature and ranged in weight from 1 pound, 14 ounces to 2 pounds, 4 ounces. Omar and Maria had weak immune systems and hematological conditions, but none of the siblings had signs of cerebral palsy or other disabilities associated with multiple births.

It was believed to be the first birth of sextuplets in San Diego County. Nurses encouraged the parents to go public so they could receive donations. A cable television station inquired about doing a show. Two other sets of sextuplets born in the United States the same year, including the Gosselins of Pennsylvania, would eventually star in reality television shows.

But on his way home from the hospital, Benigno would walk past the local media camera crews, never revealing that he was the father. He had a reason for wanting to remain anonymous.

“It was hush-hush. Some of us wanted to write to Oprah and get some help,” said Jenny Leavens, one of the nurses who cared for the children during their stay in the neonatal intensive care unit. “But they were just too fearful of being deported.”

Benigno hadn’t counted on six children. He painted houses all day, then went home to help care for the babies. But his $30,000-a-year income didn’t stretch far enough.

The family started receiving baby formula through a federal nutrition program. Although they were told by social workers that they were eligible for welfare and other benefits, Benigno and Gabriela decided against signing up for them.

“We didn’t have our papers and didn’t want to face accusations that we were getting benefits,” Gabriela said. “Who plans on having six children?”

The family relied on volunteers from a local Catholic church who gave them a van and collected donations.

Not everybody was sympathetic. Bill Hotz, a church volunteer who did the family’s laundry, said some people he knew questioned the family’s motives and the costs to taxpayers. Medi-Cal paid the family’s hospital bill.

Referring to his volunteer work, he said, “They would not have done it and didn’t understand why I was doing it.”

::

Teresa and Maria remember a monkey sticking out its tongue at the San Diego Zoo. Noe misses the French fries at “Booger King,” as he called it. Omar remembers wading into the Pacific Ocean in Encinitas. Carlos and Marcos still talk about their Legoland visit.

But the siblings’ fondest memory: their beloved casa blanca, the white house.

It was a duplex apartment in Vista, small and shabby with an oil-stained driveway. All the siblings shared one room, two triple-strollers were parked in the living room, and the backyard featured a patch of grass with an inflatable pool.

They spent Christmases at the beach, hiked nature trails and piled down slides at parks, always keeping one another close by, in rowdy orbit. When the children began attending separate kindergarten classes — two kids per room — recess would turn into joyous reunions.

“They were just so happy to see each other … that they all ran and hugged each other,” said Janet Mikelson, a former teacher at the siblings’ school, Beaumont Elementary.

One day two uniformed officers searched the apartment. They opened doors and peeked under beds and inside cabinets looking for an undocumented immigrant who lived in the apartment before they moved in.

The experience shook Gabriela. Border Patrol agents were not an uncommon sight in her neighborhood, but the prospect of deportation seemed even more real now. Agents sometimes drove by the bus stop where she waited for her kids after school. “What if they arrested me, and nobody was there to pick up my children,” she thought.

Benigno never traveled north of San Diego County on Interstate 5, mindful of the Border Patrol checkpoint near San Clemente. Though he could have used the work people offered him in Orange County, steering clear of federal authorities was now more important than ever.

To get home to Vista, Benigno would take the I-5 to California 78. The ramp was 10 miles south of the checkpoint, a safe distance from the Border Patrol, he figured.

Finally, though, the couple decided to move the children to Mexico. Gabriela would go with them; Benigno would stay behind to earn money.

On a hot day in August 2010, Benigno watched his wife and children climb into his uncle’s van. His uncle, a U.S. citizen, would drive them to the Tijuana airport.

When the children realized that Benigno was staying behind, they cried. “Come with us, Papi,” they yelled. A few hours later, they boarded the flight to Guanajuato — each child clutching a teddy bear and still wiping away tears.

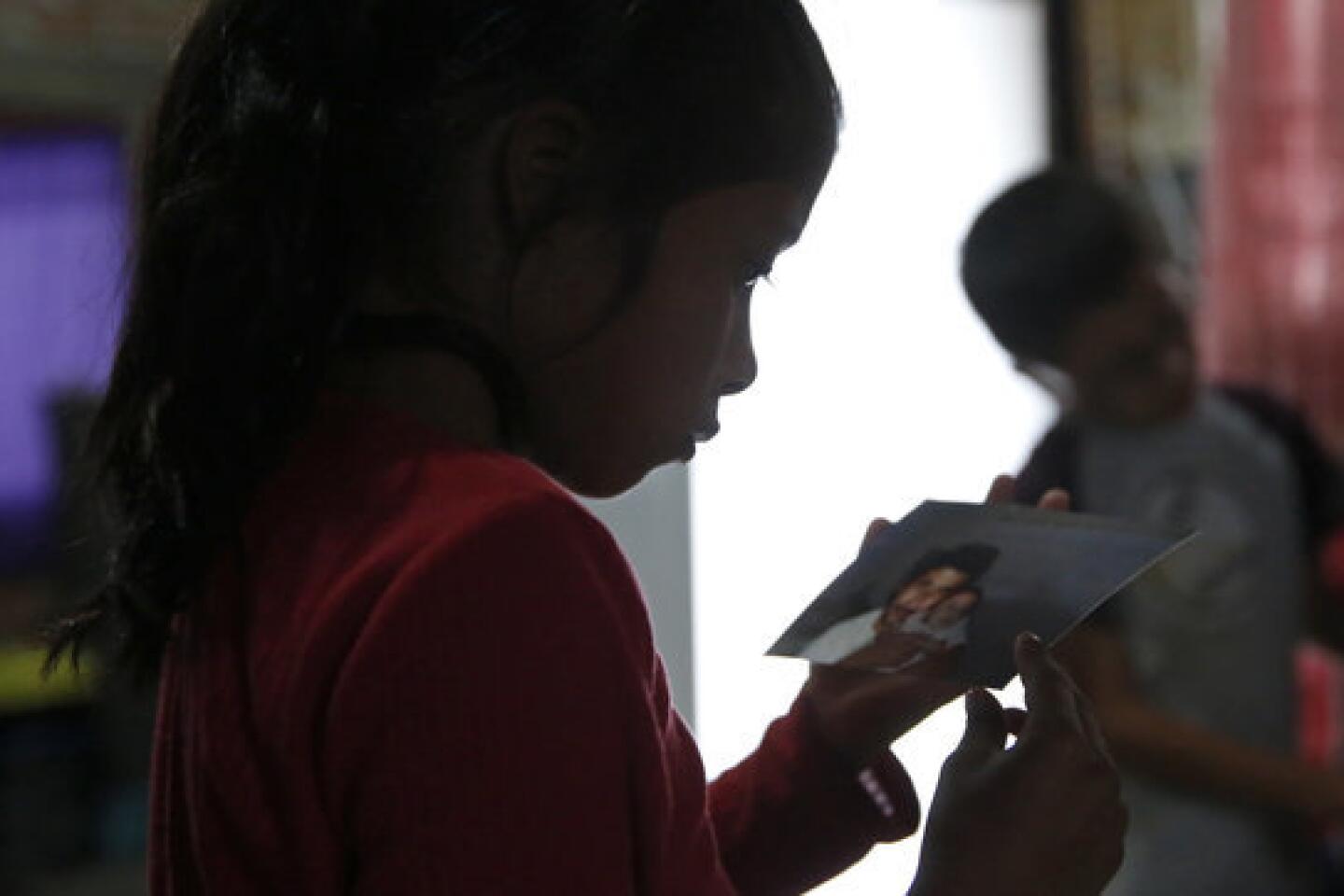

They moved into a 10-by-10-foot room at their grandmother’s home. The family slept on two beds and there was no room for their luggage. Having some of her 11 brothers and sisters close by was a relief to Gabriela. But the children missed California. When Benigno called to say hello a few days later, the children asked for a favor.

“Can you build us a white house, Papi?”

::

In San Diego, Benigno started painting houses day and night, Sundays and holidays. His customers and co-workers wondered where he got the time: “Don’t you have a family?” they’d ask. For doubters, he’d pull out piles of family photos that he kept in his paint-splattered van.

Late one afternoon in November 2010, as Benigno was on the I-5, nearing the California 78 turnoff, Border Patrol agents pulled him over.

Benigno says they asked for proof of citizenship. He said he didn’t have any. They pressed him to sign a form that would have led to his immediate deportation. He demanded to see an immigration judge.

Three years later, Benigno’s long legal battle with immigration authorities appears to be ending. Last week, Immigration and Customs Enforcement offered to suspend his deportation proceedings. Two previous requests by Benigno’s legal team had been denied, according to his San Diego-based attorney, Nicole Leon. The government’s offer came after the Los Angeles Times inquired about the status of the case.

Benigno had been preparing for an immigration hearing in October, and had filled his case file with tax returns and letters of support. “I trust him with keys to million-dollar homes on many occasions,” said one painting contractor. The doctor who oversaw the sextuplets’ delivery, David Schrimmer, wrote that separating the family “is not only cruel, it is inhumane.”

Benigno, by accepting the government’s offer, avoids a hearing’s uncertain outcome and gains permission to work in the U.S. (He had been allowed to work during the litigation). But for now, at least, he gives up his chance to get a green card.

He also faces many more years of living apart from his kids. Although his U.S.-born children can return to California, their Mexican-born mother can’t. And if Benigno goes to Mexico, the family would be reunited, but would probably plunge into poverty because he would be barred from returning to the United States.

Outside the front door of his family’s little house in Purisima de Temascatio de Arriba, a new home is rising. It’s being built by local contractors, thanks to the money sent home by Benigno. Brick walls outline several rooms and steel rebar towers hold the promise of a second story that would make the house one of the biggest in the village.

One rainy day in July, the kids played amid the bricks and wheelbarrows, scrambling through windows to stake their claim on each room. Marcos and Carlos said they would share one; the girls claimed the one nearest what will be the front door, and Omar and Noe climbed into a brick shell with a view of the surrounding fields of sorghum.

The home should be finished soon, the children said. Papi promised.

“He’s going to paint it white,” Carlos said. “It’s our favorite color.”

Times researcher Cecilia Sanchez in Mexico City contributed to this report.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.