A hostile work environment, but ‘these are not bad kids’

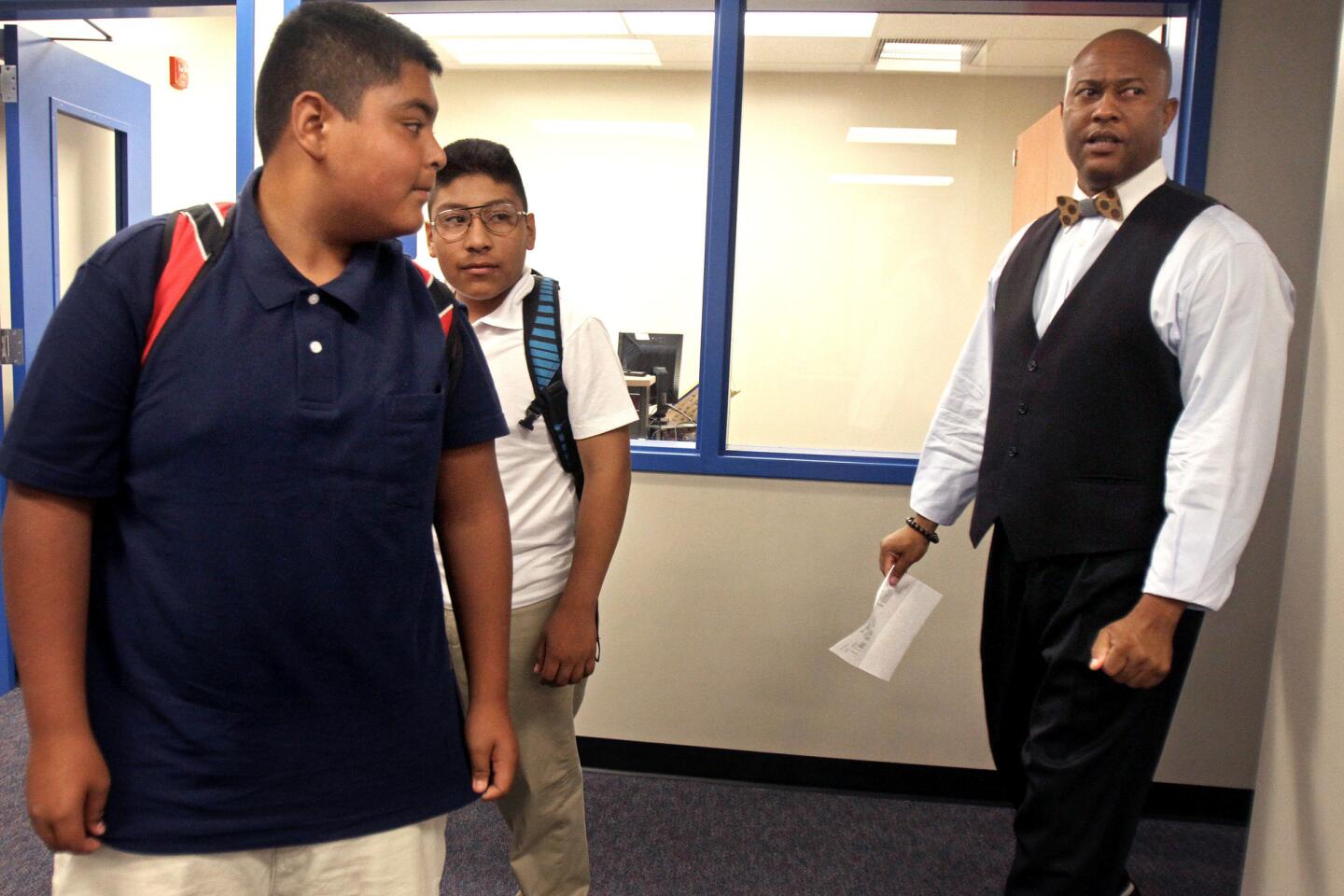

On the first day of school at Spurgeon Intermediate, after the first bell had rung and administrators swept the halls for stragglers, new Principal Todd Irving faced dozens of parents in a room near his office. A translator stood at his side.

Eliazar Arines, whose son is in the eighth grade, told Irving that last year her boy was ridiculed so mercilessly that he was hospitalized for depression.

“I came to complain five times, and no one paid attention to me,” she said, her voice cracking.

Edelmira Rodriguez told Irving her son’s ID was snatched and marked up with slurs. She too complained, and nothing was done.

One woman, who recently moved to Santa Ana from Tustin, said what many in the room were thinking:

“When someone says Spurgeon, it’s like the worst thing in the world.”

Spurgeon Intermediate in Santa Ana sits squarely in the center of one of the poorest ZIP Codes in Orange County. For years, it has consistently ranked one of the lowest-performing schools in the region. But early this year, things got even worse.

In March, 36 teachers and employees took the unusual step of filing a hostile work environment complaint against the administration and students. Children were accosting adults, smoking marijuana, making sexual noises in class, the complaint said. By the end of the school year, more than 40% of the students had been suspended for a total of more than 800 days.

Things were so bad, one teacher said, it was like “Lord of the Flies.”

::

Irving was hired over the summer to keep Spurgeon under control. The 6-foot-1 former college basketball player had two major goals: First, enforce the small rules; second, give the troublemakers some attention.

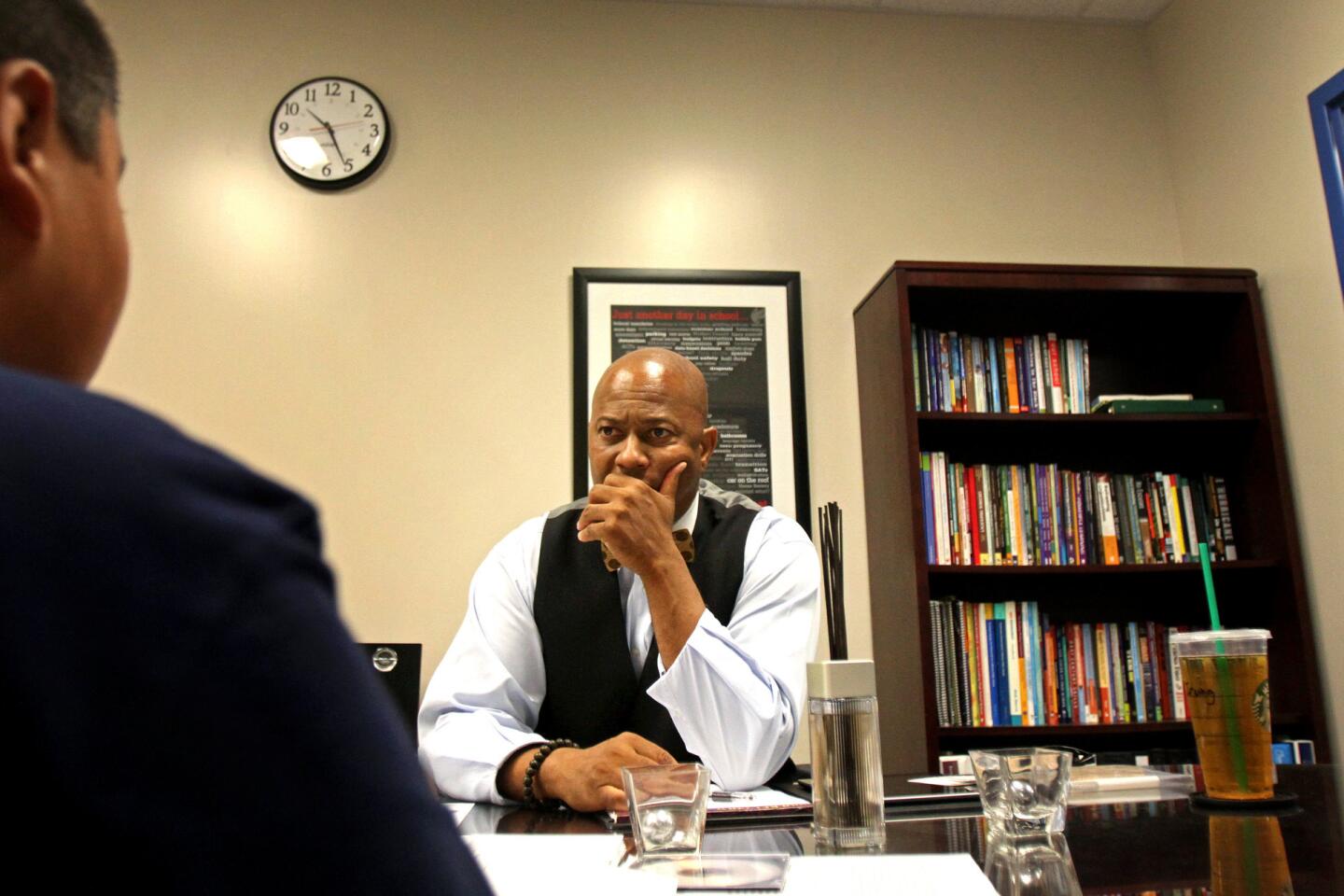

In the weeks before school began in late August, he asked his vice principals to compile a list of the school’s 50 most disruptive students and promised to be responsible for them.

Irving, 49, had been a principal at struggling urban high schools for about 14 years before he took a job at the Orange County Department of Education in hopes of one day becoming a superintendent.

Almost as soon as he took the job, he realized he missed being around students. When he read in the newspaper about out-of-control Spurgeon, he saw a chance to get back to the work he enjoyed.

At a school like Spurgeon, he said, “you aren’t going to have that kid who has a desk to work at home. You aren’t going to have that kid who has the laptop at home. So what are you going to do to make the playing field even for them?”

Over the summer, he met with each of the 50 students and their parents. The meetings gave Irving a glimpse into the problems they faced at home.

Some have trouble waking up for school because they don’t have beds to sleep in, parents explained. There are boys whose fathers are serving life in prison. Others have mothers who are being deported. Some are not yet teenagers and already are addicted to painkillers or inhalants.

“These are not bad kids,” Irving said. “We have students ... that we talk about like they’re a problem. But they come to us with problems.”

Irving, who keeps a collection of multi-colored bow ties in his office and wears one every day, is fond of making lists — the white board in his office often has dozens of bullet points, outlining goals and responsibilities for him and campus staff. He took a similarly detailed approach to the 50 students.

Each was asked to sign a contract promising to come to class every day and to follow small rules, like being on time. Teachers would assess their behavior on a scale of one to five during each period of each day. If they earned consistent marks, they could graduate from the program.

“I’m going to give her a chance,” Irving told one mother. “One thing I firmly believe is kids make mistakes.”

::

The second morning of the school year, Irving and his vice principals gathered students into assemblies by grade and took turns explaining a long list of rules and expectations — pick up your own trash, get to class on time, no fighting, no gangs, no lighters, no stink bombs, no matches.

Students sat quietly, their legs crossed on the floor and pulled at the straps of their backpacks or fiddled with binders.

“No one on this campus will be threatened by other students,” Irving told them.

That afternoon, he noticed an older man walking on campus. It was a father, angry to the point of tears. He told Irving his son was being bullied by a boy who had lost to him in a video game.

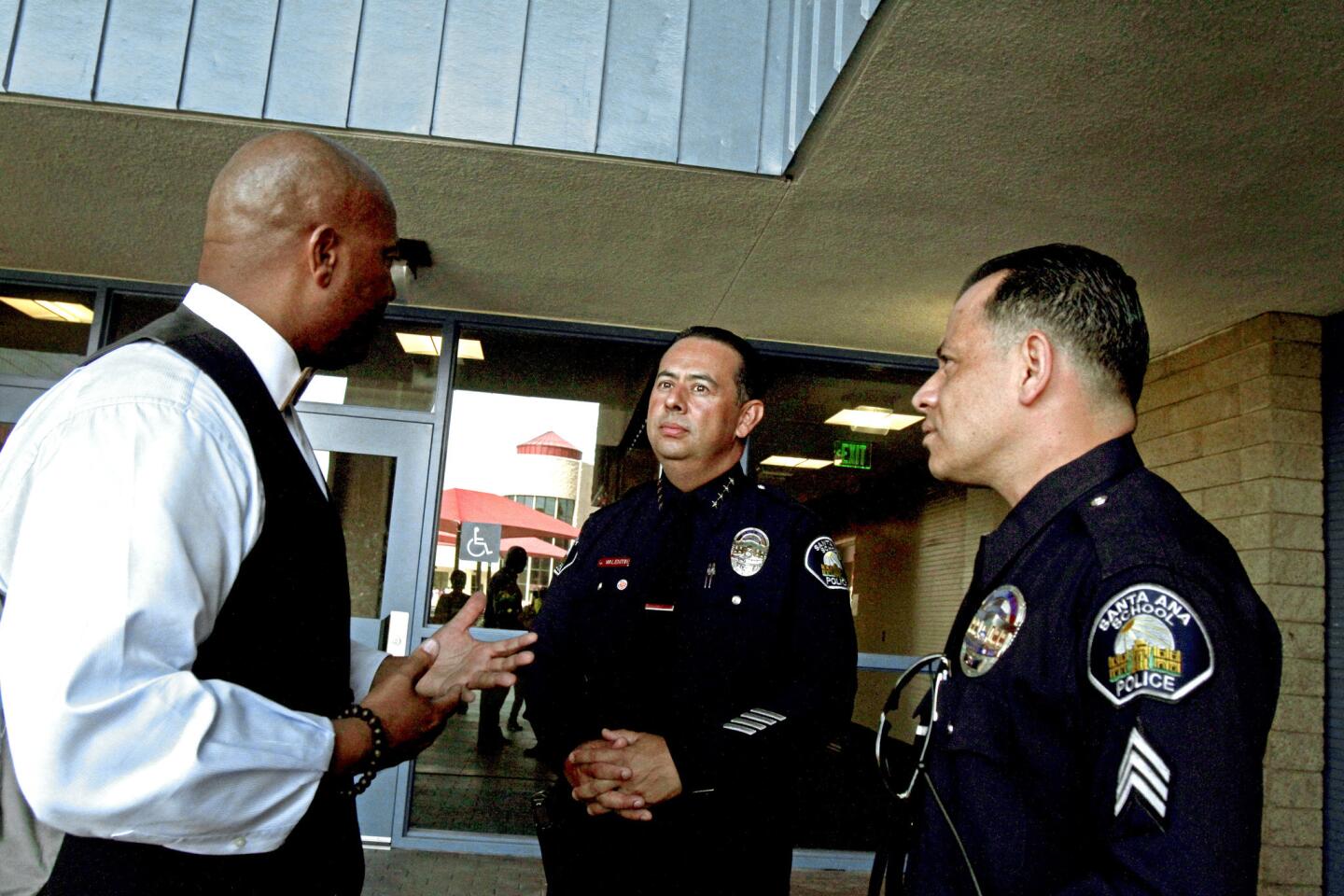

The troublemaker was a lanky eighth-grader with braces and spiked hair named Ernesto. Toward the end of the school day, Irving called in Ernesto, his mother, a counselor, translator and school police officer.

The officer stood over the boy and put his face a few inches from his.

“This is a whole different ship now,” the officer said. “Who’s the man in charge?”

“Him,” Ernesto said quietly, looking at Irving.

Ernesto’s mother leaned forward, toward the counselor and translator. “He’s like this at home,” she said. “He needs some help.”

Irving stepped in with a reassuring tone. “We’re going to work with you,” he said.

“I don’t want to go to this school,” Ernesto said.

Irving brought out the contract and asked him to sign it. He added Ernesto to the list of students he would be responsible for.

Next up was a 13-year-old boy named Anthony who teachers said was addicted to sniffing inhalants. Rather than going to the rules assembly, he had hidden in the bathroom with a friend, a bottle of spray cologne in his backpack.

Anthony’s father sat with a baby in his arms and a young daughter at his side. He too asked for help with his son. As the counselor and father talked, Irving kept his eyes on Anthony, who stared into the distance.

“Do you want to stop doing this?” he asked.

“I tried to, but I think you can’t,” the seventh-grader replied.

At the end of the meeting, Irving pulled Anthony aside and pointed at a framed photo.

“This is my oldest son, and when I saw you, you look so much like him it’s incredible,” Irving said. “We’ve got to do everything we can to help you.”

Anthony nodded, his gaze still far away.

::

On a recent morning, before the 8 a.m. bell rang, Irving stood at a busy intersection in front of Spurgeon, greeting students with a handshake, like he does most days.

Throughout the day, students are in and out of his office. He has frequent conferences with parents, sends administrators and counselors to visit students who don’t show up; sometimes he pulls troublemaking students out of class and lets them sit in his office, doing homework or just talking.

So far, suspensions are down — in the first two months of the year there were 24 days compared with 71 last year, Irving said. All but 12 of the 50 students identified as troublemakers have done well enough that they are no longer required to check in with teachers every period.

Anthony, the seventh-grader, left Spurgeon a few weeks after school began.

Ernesto, the boy who was bullying on the second day of school, has gotten in trouble multiple times since the year began. Once he went to a Garden Grove middle school and was caught telling students he was in a gang; another time he refused to come to school because he had a bad haircut. But Irving sees this as a minor issue.

“When I came here, I was expecting like Compton, South-Central L.A., East Palo Alto,” he said, listing places where he’d served as principal. “I come here, and Ernesto is the toughest one.... He’s not a bad kid. He’s a knucklehead.”

Susan Mercer, the president of the teachers union, who helped file the hostile work environment complaint, said the school was getting better.

“According to what my teachers say, they’re really happy. The school has really turned,” she said. Teacher John McGuinness agreed.

“This is a pretty easy thing in education,” he said. “If you set expectations, tell the students what’s going to happen and then actually do it, you usually find that it’s effective.”

Still, the biggest challenge remains: learning.

Irving has said he wants the school to improve on its dismal 650 state test average by 50 points this year. That would be a significant achievement — but still far below state targets.

On the first day of school, Irving explained that schools have a cycle. Students are on their best behavior at the beginning of the year. When the holidays approach, they begin testing the boundaries. By spring, if the rules aren’t enforced, things can get out of control.

So he’s trying not to get comfortable.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.